Discover where the wildflowers are truly wild

As springtime approaches, a benevolent army of hunters begins to mobilise.

It’s hard to imagine that the humble wreath flower could have a cult following. A rare plant that grows in a circle almost as big as a bicycle wheel, it resembles a wreath when crepe-like flowers form a flowery rim in soft pink, green and red.

It’s an unusual sight in the plant world, and it attracts a dedicated following as springtime approaches in the West Australian Wheatbelt region.

The wreath hunters arrive in their cars – often grey nomads towing caravans – at places like the tiny hamlet of Canna. They look for the rows of pink markers that a shopkeeper started the habit of pegging out each year.

Follow the markers, turn the final corner and there they are – dozens of colourful wreaths scattered along a roadside as if someone randomly tossed them from a passing car window.

There are even cryptic clues and hand-drawn maps handed out to the hunters: “Small cluster spotted at the side of the road, just east of Rabbit-Proof Fence” or “Starting to flower in the vicinity of the power lines”.

West Australian wildflowers attract this sort of serious sleuthing. Of course, you can drop in anytime to Kings Park and Botanical Garden, five minutes up the hill from Perth’s CBD, and find park landscapes dedicated to the state’s unique plants.

But between June and November, it’s a thrill to travel out to where the wildflowers are truly wild. They bloom in colour-drenched waves across sandplains that connect the moist coast with drier inland zones.

A typical wildflower trail will take you through northern agricultural towns like Moora, Coorow, Carnamah, Three Springs, Eneabba, Mingenew and Badgingarra.

Flower seekers are greeted warmly in tourist information centres, and directed to the best spots for massed flowerings of pink and yellow everlasting daisies.

You can almost hear the sound of vast stands of daisies, as a light breeze rustles their brittle paper-dry petals.

Elsewhere, impressionistic dabs of colour catch the eye – yellow buttons and orange immortelle, or rosy everlastings with yellow or black centres and silver bells with pink-white nodding bells.

Biodiversity is such a clunky word – far better to take an enthusiast out bush and show them the miracle of 80 different plant varieties, from big to infinitesimally small, growing within a 10 sqm plot. Or take them hiking through WA’s scrubby Kwongan heath, alive with insect-attracting blossoms.

Not many people stop to wonder why this corner of Western Australia is so blessed with one third of all known Australian plants. A simple answer is survival; the soil in this largely flat, worn-down land is so ancient and leached that every plant type has evolved in different ways to exploit its own unique niche.

That’s why Western Australia’s southwest is designated a “global biodiversity hotspot”, selected by Conservation International as the only such hotspot in Australia and one of only 35 in the world.

It means Western Australia is a place of “exceptional concentrations” of plants unique to the state – and new local species are still being discovered at a rate unrivalled by any other parts of Australia.

Sadly, “hotspot” status also denotes a place where those species are facing major threats. A “wanted” sign is pinned on the wall of a tearoom at Perenjori, a popular stop on the wildflower trail. “Wanted: If you have seen these plants please contact us”.

It goes on: “These rare species are found in very small numbers … They are threatened by land clearing, drought, weed invasion and grazing.”

Yet wildflower hunting still offers rich rewards from the bottom of the state to the Kimberley at the top.

Typically, the season begins in the north, the Pilbara and inland outback regions by June and July. Wildflowers then continue to bloom further south, including in the Wheatbelt and Perth region from August and September, and slightly later in more southerly places such as Margaret River and Albany.

You might start in the Kimberley, where good rains this year have ushered in a spectacular dry tourist season and thriving vegetation. A walker in the famous Bungle Bungle ranges at Purnululu National Park will be greeted by a mass of red pendulous blooms on stands of Prickly Grevillea, while a spray of white flowers dangles from a hardy rock grevillea clinging to the sides of the beehive-shaped cones.

On the sandplains around coastal Kalbarri further south, 800 species of plants including wildflowers start to bloom from July. They grow with such profusion you’d swear a gardener had tended them. There’s Kalbarri’s unique red-and-green kangaroo paws, Murchison claw flowers, pink pokers, Oldfield’s foxglove.

There are wavy stands of smoke bush with white hairy flowers that can only be pollinated by tiny native bees. A burly European bee hasn’t a hope.

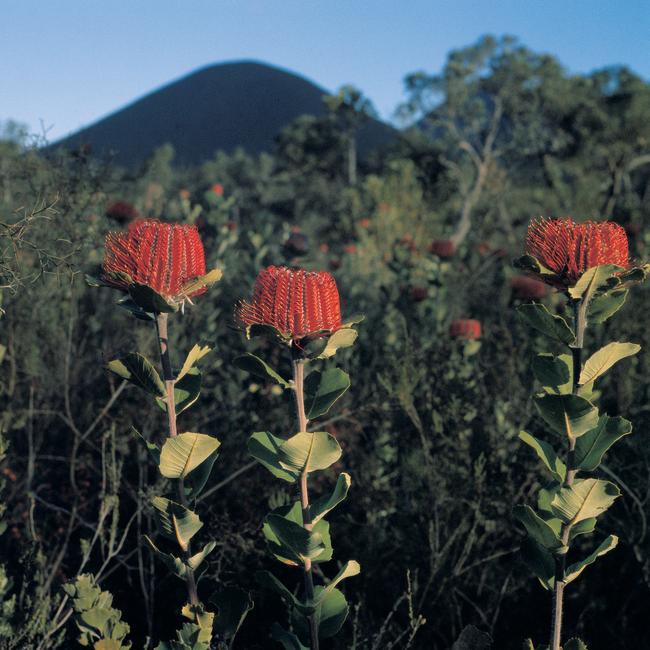

On craggy peaks of the Stirling Range, a four-hour drive southeast of Perth, you encounter hillsides of brilliant pink pixie mops, white starbursts of beard heath, orange chittick and the range’s own flame-red bottlebrush.

The showiest flowers are mountain bells, high-altitude plants with petal-like leaves that form “bells” encasing tiny hidden flowers.

All around the Stirling Range is cropping land where, in the 1950s and 1960s, millions of hectares of biodiverse native flora was pushed over, piled up and set ablaze.

Today, one of the most ambitious conservation efforts ever attempted in Australia is recreating bush corridors across 1000km of southwest country.

Called Gondwana Link, it works in various ways – a community group buys a parcel of land and revegetates it with thousands of native trees and shrubs. Or a farmer is assisted to fence off expanses of rich botanical wilderness in perpetuity.

Aided and abetted by humans, this southwest global hotspot is reviving itself and bringing back birds, insects and native animals. And as plants mature and blossom, they await the return of the flower hunters.