Defence communications satellite project gets a headstart

Rather than shortlisting two companies for a further round of studies in the acquisition of a communications satellite network, the Defence Department announced the winner was Lockheed Martin.

In a decision that predated the release of the Defence Strategic Review (DSR) – but anticipated its findings – Defence has skipped a major phase in the acquisition of a communications satellite network. Rather than shortlisting two companies for a further round of studies, on April 3 the department announced the winner was Lockheed Martin. Consequently, the project has probably regained two years of schedule.

The news took industry by surprise since it pre-empted further competition for a contract worth between $3bn and $8bn. Known as JP9102, the objective is to provide Australia with military communications satellites rather than rely on allies – mainly the US – supplemented by commercial services.

The logic is compelling: sometimes even close friends give priority to the needs of their own forces rather than ours. The alternative of relying on the private sector is a bit like Uber: while demand is low, costs are very reasonable.

However, when there is a sudden jump in demand – for example, when there is a regional crisis – the price per second of satellite bandwidth becomes prohibitively expensive. The only solution is for a country to have its own sovereign network. It is believed that in second place was the only European supplier in the race – Airbus UK – and they banked heavily on Australian content as the cornerstone of their bid. Privately they calculated that they were offering about $2bn more local investment than their competitors. In prioritising local industry, it seems they misread the tealeaves. Under the umbrella of AUKUS, the procurement debate has rapidly shifted from what can be developed locally to what can be imported.

There has been no official explanation for why there has been such a dramatic change in the process – and in a very unusual development the announcement of the winner came from the Defence department, not the government, which might indicate some sensitivity on the topic.

Lockheed Martin were always in a strong position being the supplier of a multitude of government satellites, including the US AEHF and MUOS networks, but it might also be the case that Airbus damaged their reputation with a perception of poor performance supporting Army’s Tiger and Taipan helicopters.

Lockheed Martin will now construct three satellites for Australia in the US, and they will be launched later this decade. With an expected life of around 30 years, they will be placed in geostationary orbit some 37,000km away, able to supply secure UHF communications globally but with a focus on the Indo-Pacific region. The network will be accessed by other government users such as DFAT and the AFP.

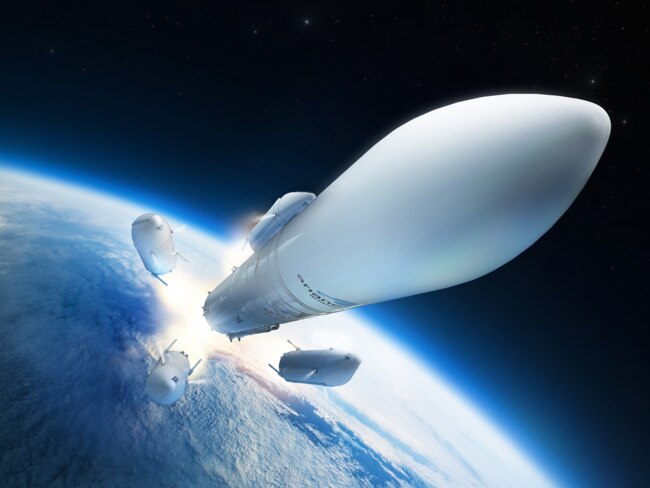

Sending a satellite weighing about 5 tonnes to a distant orbit is no easy task and there are just a handful of suppliers able to do so. The standout competitor is Arianespace, which has a long history of involvement in the Australian satellite sector with a 100 per cent success rate of launches for local customers, mainly Optus, using its Ariane 5 rockets.

The advantage the company enjoys over rivals such as SpaceX is its track record of placing satellites – particularly for military customers – very precisely in geostationary orbit. This is a somewhat technical domain relating to the velocity at which the satellite is deployed from the launcher after leaving the atmosphere, and its direction.

The life of a satellite is determined mainly by the amount of chemical fuel it carries on board. This is used in small amounts for manoeuvring and – even at a great distance from earth – counteracting the pervasive influence of tiny amounts of gravity. If a satellite leaves the launch vehicle a long way from its desired orbit, it must use quantities of irreplaceable fuel to get it to its final position.

On the other hand, if the launch rocket does all the hard work and sends the satellite accurately on its way after separation, it can save most of its fuel for minor readjustments during its long mission. For this reason, Arianespace – which is moving to the new Ariane 6 launcher – is credited with doubling the life of the James Webb telescope to 30 years by placing it more accurately than any competitor could have done at a Lagrange point some 1.5 million kilometres from Earth.