Are we facing an ‘ominous’ de facto China-Russia alliance?

The growing challenge from China tends to crowd out other threats, including those from the military alignment of Moscow and Beijing.

The commander of US Strategic Command, Admiral Charles Richard, has warned recently that it was a mistake to think about China and Russia in isolation of each other. Their continued defence relationship “should not be underestimated or ignored.”

He says the biggest nightmare for the US was that there would be even closer ties between Beijing and Moscow. This would face the US, for the first time in its history, up against two nuclear competitors instead of just one.

The growing challenge from China these days tends to crowd out attention in Australia to other enduring threats, including those coming from the military alignment of Moscow and Beijing.

Over 20 years ago, Zbigniew Brzezinski, the former national security adviser to President Jimmy Carter, said that the most dangerous scenario to the US would be a grand coalition of China and Russia, “an anti-hegemonic coalition united not by ideology but by complementary grievances”.

Earlier this year, NATO Secretary General, Jens Stoltenberg also observed that Russia and China have been co-operating more and more recently, both at a political and military level and that this new dimension was “a serious challenge for NATO”.

He said that Moscow and Beijing are increasingly co-ordinating their respective positions and, in addition, both countries conduct joint military exercises, test long-range flights with military aircraft and conduct maritime operations together, but also carry out an intense exchange of experiences on weapon systems and internet control.

This strategic partnership has deepened to provide for advanced Russian military equipment sales to China. These include sophisticated jet fighters such as the SU-35, relatively quiet Kilo class conventional submarines, advanced air defence systems such as the S-400, and – most ominously – Russian construction in China of powerful ballistic missile-attack early-warning radars.

There have been joint exercises in the Baltic and East China Sea and the rendezvous of nuclear-capable Russian and Chinese strategic bombers over the East China Sea. They have also been stepping up their co-operation on artificial intelligence.

So, the central geopolitical question is: how enduring is this relationship and is it already a de facto alliance?

Although we are clearly facing a rapidly growing military partnership between China and Russia, this does not mean a formal NATO-type alliance. Indeed, many commentators see this relationship as one merely of convenience driven by their hatred of the West. This line of reasoning concludes that when this relationship becomes inconvenient, it will be because of entrenched Russian and Chinese differences of history, race, and culture – as well as deep-seated and unresolved territorial claims.

That may well eventually be so, but in the meantime we need to focus on the friendship between the authoritarian leaders of these two countries and their mutual disdain for what they see as a rapidly declining West. The conjoining of the strategic ambitions of Beijing and Moscow highlights the differences in the global competition for power with the West and increases the potential for miscalculation and conflict.

Both Beijing and Moscow see a West that they believe is preoccupied with debilitating challenges at home. Vladimir Putin has contempt for what he sees as a Europe that is weak and divided. Xi Jinping believes that the correlation of world forces strongly favours an ascendant China. He considers that China is well on its way to becoming the predominant hegemonic power in Asia.

Thus, China and Russia have commonly perceived threats regarding the West. If their military partnership continues its upward trend, it will affect the international security order, including by attempting to undermine the system of US-centred alliances in Asia and Europe. China and Russia are allied in a quest to refashion a world order that is safe for their respective authoritarian systems. Both leaders have reason to be gratified by global trends in this regard. To use Cold War language: “the correlation of world forces” is moving in their favour.

The rapid development of China’s military capability, together with serious reforms in Russia’s conventional and nuclear forces, is occurring when the US cannot fight two major regional conflicts simultaneously.

How would Washington react if Beijing and Moscow co-ordinate a challenge by mounting attacks on Taiwan and Ukraine?

One of Russia’s leading experts on China – Alexander Lukin – has described Russia’s partnership with China as a de facto alliance. And Putin himself has said he was “not going to rule out the possibility of a more formal security relationship with China”. But Lukin (who served in the Soviet Foreign Ministry and its Embassy in China) also states that Russia understands there are limits to its strategic co-operation with China.

In the current edition of the Washington Quarterly, he proclaims that the peak of Russian-Chinese rapprochement “very likely has already passed”.

Even so, Lukin acknowledges that if the United States continues to pursue a hostile course towards both Russia and China, they will continue to maintain close relations, although he believes it is unlikely that Moscow would attempt to establish a formal alliance with China.

That being the case, the central challenge for Washington now is to detach Russia from China and draw Russia back into a larger West. But for the foreseeable future there is little prospect of inveigling Russia to ditch its relationship with China while gambling on improving its hostile relations with the US and NATO Europe. But that must remain the aim of the US if it is to reassert its leadership of the global balance of power.

The implications of all this for Australia are that we need to understand that our American ally now faces two major power adversaries and not just China. And we also need to be alert to the fact that Russia is helping China by selling it more advanced military equipment, which one day may be used against us.

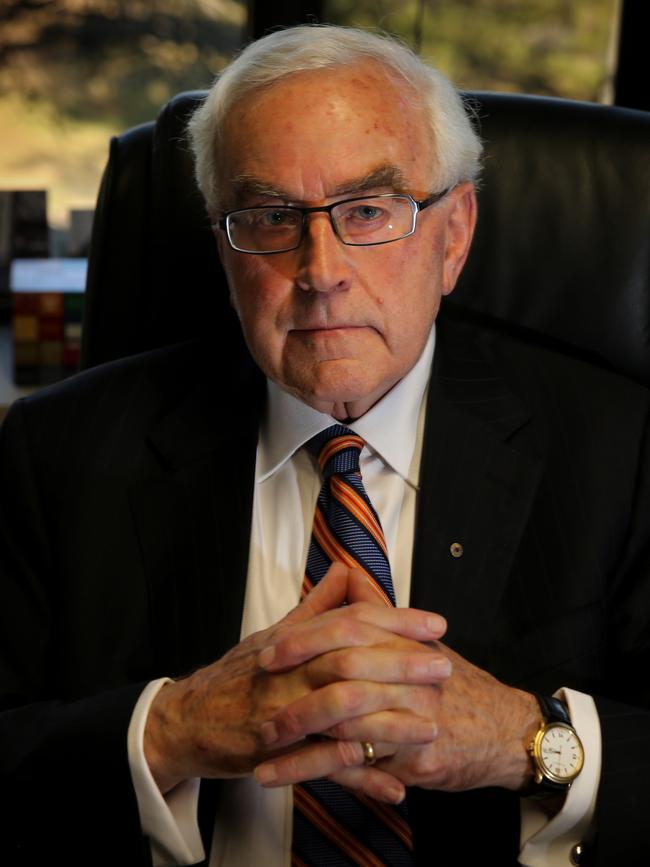

Paul Dibb is emeritus professor of strategic studies at the ANU.