AI revolutionises maritime intelligence

New sources of maritime intelligence now have the potential to revolutionise the Indian Ocean, by making much of the ocean observed spaces at relatively low cost.

Piracy, drug trafficking, people smuggling and illegal fishing are among the many maritime security challenges faced in the Indian Ocean. Many littoral countries are increasingly aware of the importance of Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) as a foundation for effective maritime governance. New sources of maritime intelligence now also have the potential to revolutionise this area, by making much of the ocean observed spaces at relatively low cost.

Achieving MDA typically involves integrating information from numerous sources, such as automatic identification systems (AIS), vessel monitoring systems, vessel registries, port intelligence, coastal radar, aircraft, satellites, ocean users, shipping companies, and many more.

Data from these different sources is “fused” and then analysed to produce operational intelligence as the basis for decision-making on response.

During the last couple of decades, many Indian Ocean countries have established national MDA centres. This not only includes naval powers such as Australia and India, but increasingly smaller or less wealthy countries such as Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Maldives. This reflects sovereign imperatives to understand what is happening in their maritime jurisdictions.

Another development is the establishment of regional information fusion centres to facilitate the sharing of information on a regional basis – including centres in Singapore, New Delhi, Madagascar and the Persian Gulf. But regional information sharing systems are still very basic. Partners have no direct network access to regional centres and, instead, information is shared by email by foreign liaison officers. This limits their utility as a source of real time operational intelligence.

Many countries are now increasingly relying on web-based platforms as their principal source of maritime information and intelligence. These allow users to directly access and share new sources of data such as low-earth orbit satellite imagery as well as new analytical tools such as machine learning algorithmic tools and predictive digital modelling.

The US-sponsored SeaVision platform is provided to several Indo-Pacific partners as part of the Quad’s Indo-Pacific MDA Initiative. SeaVision builds on basic AIS data with overlays of satellite data obtained from private and public satellite systems from the US, Europe and elsewhere.

Another is the EU-sponsored IORIS (Indo Pacific Regional Information Sharing) system which also provides basic AIS data with satellite overlays. Many Indian Ocean countries largely use IORIS as a communications tool to share information among maritime agencies from different countries for specific tasks, such as search and rescue operations. IORIS is also building a system called “Share It” that would link IORIS with SeaVision and other platforms. We are also seeing the proliferation of many web-based maritime intelligence products provided by NGOs and private companies that give users access to data and intelligence from new sources.

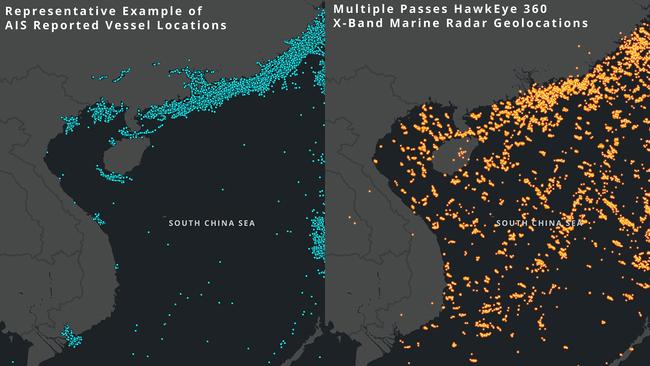

For example, HawkEye 360 offers a range of MDA products on a commercial basis, including satellite-based radio frequency data to help identify so-called “dark” vessels. This detects RF transmissions from vessels that have otherwise switched off or “spoofed” their AIS devices. The US offers HawkEye 360 to SeaVision users in various access levels, although it’s constrained by costs.

Many other private companies offer specialised maritime intelligence and MDA products on a commercial basis. These include Windward (commercial shipping, logistics, sanctions), Starboard (biosecurity and fisheries surveillance), and ICEYE, (the world’s largest search and rescue satellite constellation).

Another popular platform is Skylight, which is provided at minimal cost by an NGO funded by the estate of Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen. Skylight uses data from multiple sources including AIS, Global Fishing Watch, the European Sentinel 1 and 2, and Night Lights satellites. Skylight also receives data from its commercial partners Spire and Maxar, and soon also data from ICEYE Synthetic Aperture Radar.

Skylight then applies AI algorithms to data to produce operational intelligence on dark vessels and dark rendezvous, sometimes within minutes. Although Skylight is principally focused on the prevention of IUU (illegal, unreported and unregulated) fishing, it’s also proving to be a valuable tool that can be used for many purposes at an economical price.

While most MDA systems now focus on the activities of surface vessels, they will increasingly also need to integrate data on the underwater domain, including hydrographic and oceanographic data and information on seabed critical infrastructure and submarine actors.

Some Indian Ocean countries are reluctant to use some of these new platforms or data sources, perhaps driven by information security issues or by a desire to promote national systems. Sometimes the reasons have more to do with politics. For example, India and Australia have both decided not to use IORIS, while Indonesia doesn’t utilise Skylight data. But for smaller or less wealthy countries around the Indian Ocean, the proliferation of new MDA systems can be an important way of democratising and diversifying their sources of data and maritime intelligence – meaning they don’t need to rely so much on major powers.

However, web-based platforms that give direct and timely access to high-quality operational intelligence and analytics could also allow users to leap-frog the older “bricks and mortar” systems. They have the potential to revolutionise MDA, for the first time making broad swathes of the ocean observed spaces at relatively low cost. In future we might see traditional fusion centres operated by navies, with their walls of screens and banks of military analysts, replaced by a lieutenant with a laptop.

-

David Brewster is a senior research fellow at the National Security College. Anthony Bergin is a senior fellow at Strategic Analysis Australia and an expert associate at the NSC.