Australian stars who reached for the moon in 1969

They are the Australian heroes of the 1969 moon landing; staff at our tracking stations who were a vital part of the Apollo mission.

They are the Australian heroes of the 1969 moon landing.

Fifty years ago this month, the men and women who staffed the Parkes, Honeysuckle Creek and Tidbinbilla tracking stations sourced the weak, fragile radio feed emanating from the Apollo 11 Lunar Module on the moon’s surface, and brought the telecasts of man’s first footsteps on an alien body to hundreds of millions around the world.

They also monitored the radio data carrying information about the performance of the Lunar Module and Command Module orbiting the moon, and the astronauts’ health. Sadly, the ranks are thinning of astronomers, physicists, engineers and technicians who worked at those stations. Only around half the astronauts who flew to the moon are alive.

Nevertheless the 50th anniversary celebration shapes as a chance for amazing stories to be exchanged. Parkes Observatory is holding open days on July 20 and 21, and some staff from the Apollo 11 days will be there, along with mission experts.

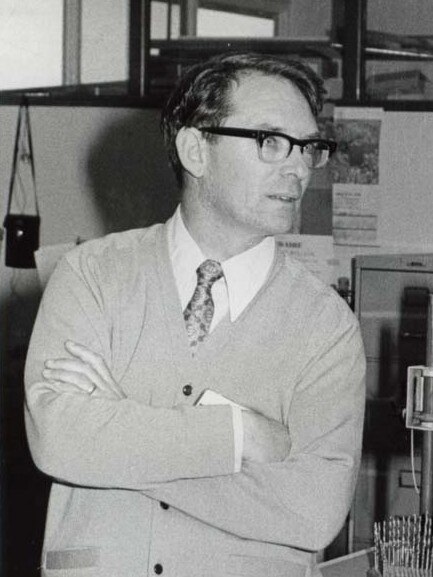

Parkes radio engineer David Cooke, 87, this week spoke of the intricate planning that took place months before the mission, and the amazing judgment of then director John Bolton to keep the Parkes dish operating during the lunar telecast, despite wind gusts of up to 110km/hr when the dish’s safety rating was 40km/hr. It could have come crashing down on them, but it didn’t.

They were the worst wind gusts that Parkes had experienced since its opening and occurred as the station was readying to relay Apollo 11’s signal to the world. Mr Cooke said the dish was at its most vulnerable angle, on its side, pointing at the horizon as the moon rose.

The storm over Australia can be seen on a photo of Earth taken from the moon by Aldrin.

Mr Bolton could have taken Parkes offline to protect its dish, as Honeysuckle Creek and Goldstone Observatory in California both could see the moon and access the feed for the TV pictures.

At 64-metres, Parkes’s dish was larger and it could produce a better TV signal. Mr Cooke said staff didn’t want to lose their chance to make history. “It would be very poor if we gave it away.”

Mr Cooke said staff inside the telescope were far too busy to celebrate. There was some cheering when Armstrong stepped onto lunar soil, and some mild celebrations at day’s end.

He remembers later coming out of the telescope room, looking at the moon, and being amazed that three earthlings were up there. He also remembers coming home to his daughter, who told him excitedly that she had seen the telecast, unaware of the role he played in it.

As was the case with the Apollo 11 mission generally, lots didn’t go according to plan. Astronauts and ground staff were left with hard decisions that could have easily turned Apollo 11 from triumph to disaster if wrong choices were made.

Mr Cooke said Mr Bolton had backup plans for every potential mishap. Staff were taught how to crank the dish by hand should it lose the ability to move. During the landing event, the tracking station shifted to diesel power to circumvent any mains power blackout.

CSIRO present-day operations scientist at Parkes John Sarkissian said there were two TV feeds. Australians viewed the first seven minutes from Honeysuckle Creek as the moon wasn’t high enough in the sky for the Parkes dish to see it. Transmissions then shifted to Parkes.

The international TV feed switched between Honeysuckle Creek, Parkes and Goldstone several times before staying with Parkes. Mr Sarkissian said a fire in the power supply of the transmitter at the Tidbinbilla station just two days beforehand saw it ruled out from the telecasts.

Mike Dinn, who was Deputy Station Director at Honeysuckle Creek, said he was working at the operations console and Honeysuckle Creek tracked the Lunar Module that day. About 23 staff worked at the centre and people had trained for the landing event for months.

He said Honeysuckle Creek had built up competence and confidence from taking part in earlier Apollo missions. But he said you’d quietly think about the “what ifs”if things went awry.

“My job was to keep the data flowing that was coming down from the spacecraft and ship it out the Houston,” Mr Dinn said. The data comprised the astronaut’s voice, spacecraft performance and astronauts’ biomedical information, and finally the TV feed, Mr Dinn said.

He remembered being worried about an “intermittent problem” with the heart rate feed of one of the astronauts.

Mr Sarkissian said the public didn’t realise how hugely risky the moon mission was and how basic equipment was. So much didn’t go according to plan.

He said the computer’s memory on Apollo 11 was only “a few kilobytes”. The memory was stitched together manually. Stitches threaded in one direction represented a “zero” while those threaded the other way were “one”.

As Armstrong and Aldrin descended in the Lunar Module, the computer froze with 1201 and 1202 errors which the pair didn’t know how to interpret. The errors weren’t listed in any manual. Mr Sarkissian said Armstrong wanted to know whether to abort the landing.

Fortunately, the same error had occurred in a simulation weeks earlier with controllers wrongly suggesting an abort. NASA flight director Gene Kranz had told staff to go away and study the codes and their meanings.

Armstrong ignored the issue as he had another huge one. The Lunar Module had overshot the landing spot by about six kilometres and was heading for a boulder field on the side of a crater. Armstrong took manual control and found a flat area beyond the crater. There was only around 20 seconds of fuel left.

Mr Sarkissian said Armstrong’s landing was softer than NASA bargained for. The module was designed to land harder with the bottom rung of the ladder just above the ground. Instead it was way above it, and Armstrong had to test whether he could climb back in from the lunar surface.

He said Armstrong’s heart rate was measured at 156 beats per minute while landing. “For Neil Armstrong, the test pilot, the real achievement was to land. Coming out and walking later on was the easy part,” he said.

The Australian tracking stations took part in some later Apollo missions. But the Apollo program fell out of favour quickly. NASA had its budget reined in, and three missions were cancelled in a little more than a year after Armstrong and Aldrin walked on the moon. It wasn’t just money. The failure of Apollo 13 with near tragic consequences disturbed many.

Mr Sarkissian said the Apollo program very much hinged on the politics of 1961 when President John Kennedy announced the US plan for a moon landing. “It was a Cold War exercise and it has to be seen in the context of 1961.”

He said the Soviet Union had beaten the US in space several times. They had launched the first satellite Sputnik 1 in 1957 and they had launched an unmanned spacecraft to the moon and photographing its far side.

Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space in just a few weeks into the Kennedy administration. The US was beaten again.

Just days later, a botched invasion of Cuba took place at the Bay of Pig. It was a political and military disaster. The Berlin Wall was constructed the same year.

Mr Sarkissian said then vice president and later president Lyndon Johnson proposed the moon landing to Kennedy as one response to restore American pride. The US believed it could match the Soviets with its big Saturn Rocket technology, he said.

But the US congress was always cautious about the moon plan and Mr Sarkissian said it probably wouldn’t have survived had Kennedy not been assassinated. The project proceeded but by the late 60s, US politics and culture was completely different with the country consumed with the Vietnam War and a big protest movement. Landing on the moon was a debt to the earlier period of the Cold War.

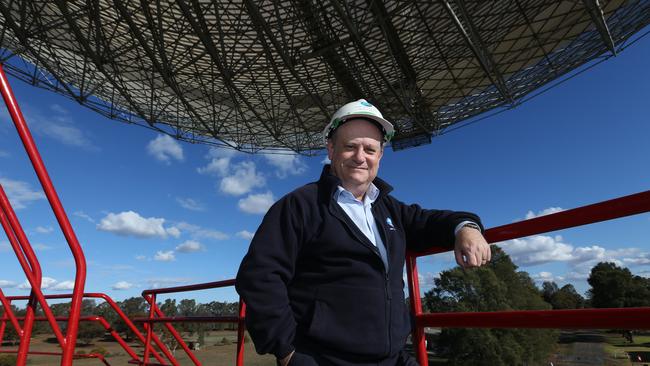

So what now for the big 58-year-old, 64-metre diameter dish at Parkes, 50 years on from the moon landing?

Mr Sarkissian says that while the “skeleton” of the dish is the same, its electronic systems are totally different and very modern. These days it’s being used by scientists around the world. When we visited Parkes this week, its dish was being operated from Beijing.

The Parkes tracking facility nowadays has a different charter as it has proved a trailblazer in NASA’s Deep Space Tracking Network. CSIRO scientists see deep space as the continued role for the Dish, rather than any specified role associated with NASA’s upcoming quest to visit Mars.

CSIRO astrophysicist at Parkes, Jane Kaczmarek, said that instead of tracking Apollo missions, Parkes this year tracked Voyager 2, a space probe launched by NASA in 1977 that this year travelled through the Heliopause, the boundary where the solar system ends and interstellar space begins. It’s 18bn kilometres from The Sun.

“It's that balance point when all the winds from all of the stars in our entire galaxy, balances with the wind from our Sun. It’s the outer skin of our solar system. One of the unique things about Voyager 2 is that their magnetic fields detector was still working.”

Scientists now know that the Heliopause protects our solar system from huge amounts of cosmic rays coming from across space.

What about Australia’s role in space travel generally? Deputy Director, CSIRO Astronomy and Space science Sarah Pearce said Australia’s expertise in mining and remote operations will be invaluable as humans venture further into space.

“We have a very strong mining, robotics and autonomous operations sector, and I think that we and certainly the (Australian) space agency have identified as potentially an area where Australia can contribute to these large international missions.

“One of the things that CSIRO and the space agency are now focusing on is making those connections. We have this world leading capability, but in many aspects of it, we haven't yet applied it to space.”

Dr Pearce said CSIRO’s future science platform was investigating how Australia could make its way into the space industry in those areas.

Apollo 11 resoundingly succeeded in getting mankind to the moon and back safely as Kennedy proposed in 1961, but it was geared to happen quickly. The upcoming challenge of garnering the resources to live far from earth for lengthy periods is massive, even when compared to the amazing feats achieved by the disciplined and incredibly alert and fast-thinking astronauts and ground staff in the 1960s.

—

The world was totally engaged

I turned 12 about 10 days after the moon landing — this was (and I feel still is) mankind’s greatest achievement.

In the months leading up to the landing, the process for this mission was drawn on blackboards in our classroom and discussed in depth. Newspaper articles had double-page diagrams of every detail of this mission — the world was totally engaged with “our” moon mission. At the time, 1969, a group of us neighbourhood boys would build our own rockets and launch them at the “forty acres”, now the site of the submarine corporation at Outer Harbour in Adelaide.

On top of the rocket we would put our astronauts — ants in an aluminium “capsule”. Retrieving the capsule, we would most often find the ant alive. The propellant we used in our rocket(s) was more powerful than gunpowder — definitely risky work — but it was the days of “cracker night”.

I am quite excited about the anniversary of our moon landing. Watching those grainy black and white images of the “walk” unfold live on TV was just incredible.

David Vuchich, Largs Bay, SA

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout