Bronwyn’s body may lie dumped in Lake Ainsworth, brother Andy Read says

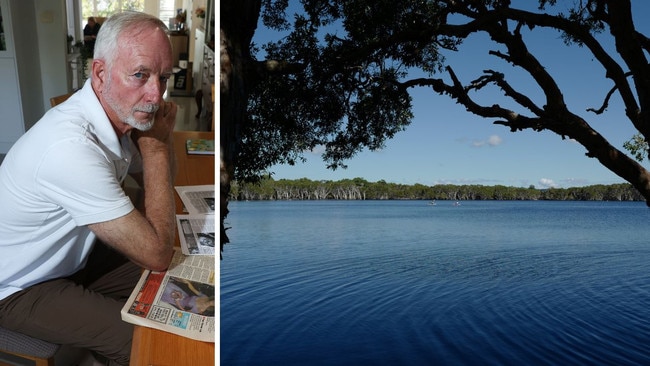

The dark, tannin-stained waters of Lake Ainsworth near Lennox Heads on the NSW far north coast may be the last resting place of missing mother Bronwyn Winfield, according to relatives.

The dark, tannin-stained waters of Lake Ainsworth near Lennox Head on the NSW far north coast may be the last resting place of missing mother Bronwyn Winfield, according to her relatives.

Bronwyn’s brother Andy Read and others have told The Australian’s Bronwyn podcast that the 31-year-old’s body may have been weighted and dumped in the freshwater lake after she disappeared on Sunday, May 16, 1993.

The lake was a short 10-minute drive from where Bronwyn was last seen at her family home in Sandstone Crescent, just south of the village.

Mr Read said “if you’re looking for a body of water” to dispose of a body, it would have to be Lake Ainsworth.

“It’s a dark lake,” he said. “It’s completely filled with tannin from the tea-trees. By the time you put your arm in the water and you go to the length of your arm, the chances are you can’t even see your hand.

“It was a lovely, safe place to take the kids and swim without worrying about rips and things like that. But everyone was always mindful to keep an eye on the kids because if they went off the sand bank into the deeper water, you got Buckley’s of finding them.”

He said there were ample access points to the lake where a car could be backed up virtually to the water’s edge. At its main basin, Lake Ainsworth drops to a depth of about 9m. “The street on the right-hand side of the lake … if you go up there, you can nearly, at some points, back your car or park right beside the edge of the road, and the water’s right next to you,” he said.

“Back then, it was a road in and out.”

The renewed theories about Bronwyn’s whereabouts have been prompted by the recent bombshell claims to the podcast of neighbour Judy Singh, who said she believed she saw Bronwyn’s husband, Jon Winfield, drive past her house late on that Sunday night with what looked like a sheet-wrapped corpse in the back seat of his Ford Falcon. She also noticed a surfboard in the car.

At the time, Ms Singh lived in Granite Street, just 50m from the Winfield family home in Sandstone Crescent.

For decades, Bronwyn’s relations wondered what happened to her body. After Ms Singh’s allegations – she was interviewed last week be members of the NSW police unsolved homicide unit – the family now said it believed Bronwyn’s remains were closer to home in Lennox Head.

“Go down to Lake Ainsworth (at night),” Mr Read said. “It’s not lit up. I believe everything would have been floated out on the surfboard. Swim out with your arm over the top of the board using your legs.

“And use your other arm. Swim all the way out … to the middle. Tip it (the body). She’s not going to float very well. Jump back on. Paddle back in. Job done, 10 minutes flat. It’s a terrible thing to be thinking of but makes sense.”

Friends and neighbours of Bronwyn also favoured Lake Ainsworth as the place where her body might have been concealed, possibly in a polyester surf board bag.

In March 1993, Bronwyn and her husband were separated.

She was renting a small flat near the outskirts of town and living with her two daughters – Chrystal, then 10, and Lauren, then 5. Two months later, while Mr Winfield was working in Sydney, she decided to move back into the family home. The locks had been changed but she contacted a locksmith and gained entry to the property.

Bronwyn had already engaged lawyers to sort through a potential child custody and marital assets dispute.

Mr Winfield, when he learned his wife was living back in the Sandstone Crescent house, flew from Sydney to Ballina on May 16 and confronted her. Chrystal, according to a statement she later gave police, remembered her parents fighting and her mother crying that night.

Mr Winfield would tell detectives his wife said she needed time out from the children and was picked up at the house by a stranger and driven away. He then decided to drive through the night back to Sydney with the children.

Bronwyn has not been seen since.

The allegations made by Ms Singh, however, up-ended the known timeline of the case, established over more than three decades. Mr Winfield repeatedly cited – including to police in his only formal interview in 1998 – a receipt for fuel he says he purchased at exactly 11.06pm on that Sunday, implying the receipt proved he was out of Lennox Head and on his way to Sydney by then.

Ms Singh’s sighting of the possible body in the car, however, was close to midnight.

And Chrystal would later tell her uncle and aunt – Andy and Michelle Read – that she believed she was woken by her father that night to travel to Sydney by car at around 1am.

This variation on the previously accepted timeline has prompted speculation Bronwyn’s remains had been dumped in the popular lake – a place where the young mother had taken her children on family picnics before she disappeared.

The lowland “dunal” freshwater 12.4ha lake, just north of the seaside village, has for more than a century been a popular recreational area for locals and visitors. It was named after a local pioneering farming family.

It was permanently brown due to the tannins leaching into the water from the swamp paperbarks that surrounded it. In Indigenous culture, it was an important place for women during and after childbirth because of the waters’ healing properties.

Generations of children across the country remembered Lake Ainsworth as the location of school holiday camps.

The National Fitness Movement opened the first camp on the shores of the lake in January 1944. A report that year into the camp location praised the lake as an “excellent swimming place, being free from currents and sharks and having a hard sandy bed without weeds”.

Today, the NSW government’s Lake Ainsworth Sport and Recreation Centre continues to host school camps, with activities including kayaking, raft building and marine studies.

The lake has also been the scene of tragedy. In March 1933, Noel Curtis, 7, drowned when he “ran out of his depth” and disappeared into the dark water. In 1949, a 16-year-old camp instructor fractured her neck when she fell off one of the lake’s high-diving towers. It nevertheless remained a popular Lennox attraction, especially in summer.

On Sunday, more than 70 locals and visitors – including dog walkers and young families – milled around the Lennox surf club, near the southern tip of the lake, drinking coffee and enjoying music from a local band.

Jon Winfield has always strenuously denied any involvement in the disappearance of Bronwyn. He has never been charged in relation to the case of his missing wife.

Do you know something about this case? Contact Hedley Thomas confidentially at bronwyn@theaustralian.com.au

To subscribe to our weekly Bronwyn podcast newsletter, click here.

To join in the discussion in our Bronwyn podcast Facebook group, click here.