Bronwyn podcast: Top prosecutor Nicholas Cowdery stands by calls on missing women

Australia’s longest-serving DPP said he could not recall the case of missing mother Bronwyn Winfield but he would not do things differently today | LISTEN

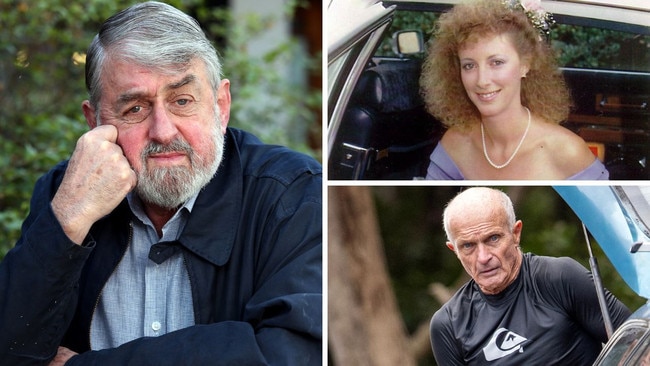

Former NSW director of public prosecutions Nicholas Cowdery KC says he would not change a thing about his approach to the suspected murders of missing women, as his refusal to prosecute husbands in two separate cases comes under scrutiny.

Australia’s longest-serving DPP told The Australian he could not recall the case of missing mother Bronwyn Winfield but he would not do things differently today in cases like it. “My approach would be exactly the same. I would look at the facts that were able to be proved on the evidence, I would look at the law and I would look at the prosecution guidelines,” he said.

“They were taken into account then, and they are taken into account now by the DPP.”

As DPP from 1994 to 2011, Mr Cowdery declined to prosecute Winfield’s husband, Jonathon, over her alleged murder, despite a senior coroner finding there was a reasonable prospect a jury would convict him.

Separately, he also repeatedly refused to prosecute former professional footballer Chris Dawson over the 1982 murder of his missing wife, now known as Lyn Simms at the request of her family. Two coroners had recommended Dawson be prosecuted.

Mr Cowdery angered Simms’s family when he said in a televised interview in 2018 that the lack of a body or cause of death in the case made it “very weak”.

The office he formerly led was considering whether to charge Dawson with Simms’s murder at the time of the interview. Dawson was subsequently convicted of murdering Simms, 33, whose remains have never been found.

Dawson did not report his wife missing until six weeks after she vanished from her home on Sydney’s northern beaches, and it was treated as a missing persons case for eight years before being seriously investigated.

In the Winfield case, Mr Cowdery also cited a lack of a body or cause of death in a letter to Bronwyn’s brother Andy Read and his wife, Michelle, explaining why he was not prosecuting Bronwyn’s husband.

The letter, dated February 19, 2003, was obtained by The Australian’s new investigative podcast series, Bronwyn.

“Bronwyn’s disappearance was not reported to police for two weeks and was initially treated as a missing person inquiry,” Mr Cowdery stated in the letter. “By the time it was dealt with as a possible homicide, years had passed and any potential scientific evidence was long gone. There is no body and no known cause of death.

“While Jonathon Winfield is the last known person to have seen her alive, there is no evidence that he killed her or had any role in her disappearance. Suspicion cannot be a substitution for evidence.”

Then-deputy state coroner Carl Milovanovich had in May 2002 suspended an inquest into Bronwyn Winfield’s disappearance and recommended the DPP prosecute a known person, Mr Winfield, over her alleged murder.

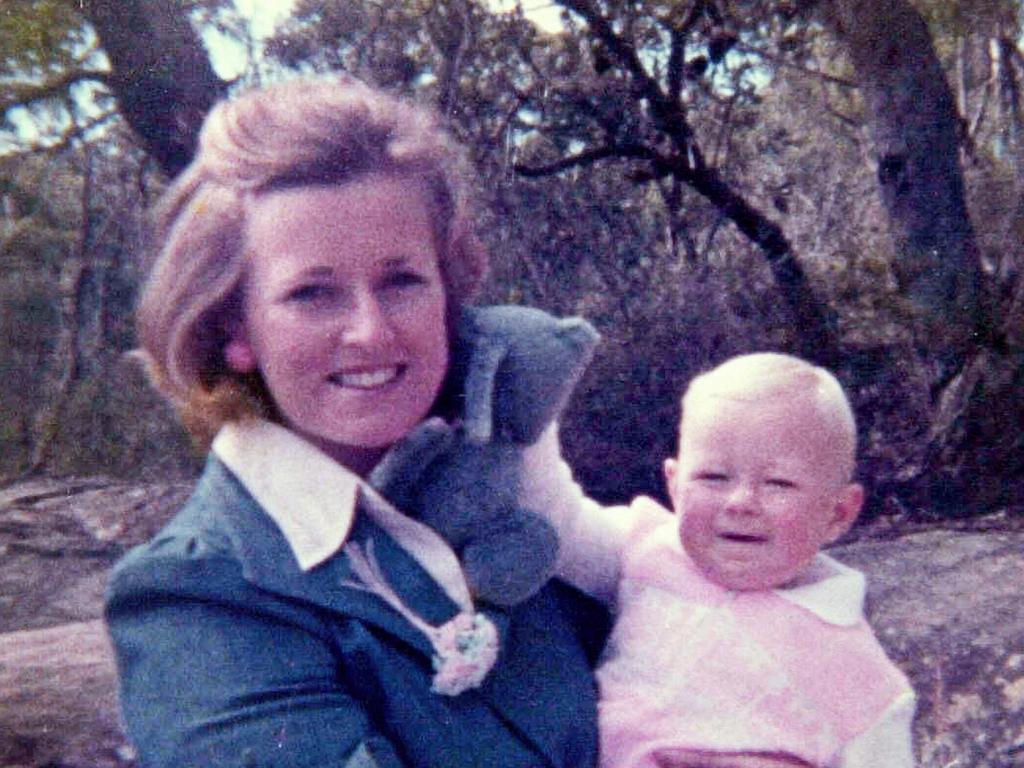

Mr Milovanovich covered a large amount of evidence over five days of hearings in a courtroom in Lismore. He was satisfied Bronwyn Winfield “died on or about” May 16, 1993, the date the devoted mother of two young girls vanished from Lennox Head on the NSW far north coast.

“The evidence is capable of satisfying a jury beyond reasonable doubt that a known person has committed an indictable offence, and there is a reasonable prospect a jury would convict,” the coroner concluded, according to inquest transcripts seen by the podcast.

The NSW DPP has looked at the Winfield case since Mr Cowdery left the role, advising in 2013 and 2014 that there wouldn’t be a prosecution without significant new material, police say.

Mr Winfield has always denied any involvement in the disappearance of his wife, then 31, and has never been charged with any offence in connection with it. He says he gave police a statement in 1998, confirmed that version in 2010, and stands by it today.

Mr Milovanovich has said he believed there were serious problems in the way police historically treated missing women. In an interview on the Bronwyn podcast, the retired coroner said there was a “systemic attitude” of police waiting for a smoking gun before investigating, and of assuming women would “turn up or they’ve gone off with a boyfriend”.

He had no doubt, he said, that a significant number of women who had been classified by police as missing were more likely to have been murdered.

The Winfield case was one of many thousands Mr Cowdery would have dealt with as DPP. “I have no recollection (of the case), I’m afraid. I had 16½ years of cases and I don’t remember all of them,” he said last week. “If that’s what I said at the time, it would have been based on evidence available.”

Now 78 and retired, he said it was “not uncommon” for a DPP’s decision to differ from a coroner’s recommendation. “It happens quite frequently, and it comes from an independent, fresh assessment of the evidence that is produced to the DPP and any subsequent investigations that might occur and so on,” he said.

“The DPP makes an independent decision about those things taking into account the recommendation and taking into account evidence at the inquest.”

Circumstantial evidence was “of course” considered evidence, and it was “not essential for there to be a body” to prosecute, he said.

“Sometimes the strongest cases are built entirely on circumstantial evidence,” he said.

However the absence of a body could make it more difficult to prosecute, as “the presence of a body leads, or may lead, to the discovery of more evidence of how the person died”.

Mr Cowdery spoke about the Dawson case on the ABC’s Australian Story in 2018 after The Australian’s podcast The Teacher’s Pet brought global attention to the case.

“Without a body, without knowing first of all if she is dead, without knowing secondly, if she is dead, how she died, it’s very hard to mount a case of a reasonable prospect of conviction just on motive and the undefined existence of means and opportunity. That makes it very weak,” he told the program.

Although the two cases have involved some of the same people, the fact Dawson was convicted does not mean that Mr Winfield had any involvement in his former wife’s disappearance.

Bronwyn separated from her husband on March 21, 1993, and she and the children moved into a rented townhouse.

Less than two months later, with Mr Winfield working in Sydney, she took the advice of family and solicitors and moved back into the family home that her husband built at Sandstone Crescent.

Mr Winfield had changed the locks but she called a locksmith and gained access.

On hearing his wife had moved back into the home, Mr Winfield flew from Sydney to Ballina and returned to Sandstone Crescent on May 16, 1993.

Bronwyn put her daughters Chrystal and Lauren, then 10 and 5, to bed that night and was never seen or heard from again.

Mr Winfield woke the two little girls, put them in the family’s Ford Falcon, and left the home around 10.40pm, driving through the night to Sydney.

Bronwyn had met lawyers seeking a division of marital assets including the family home, and had an appointment booked with one the next day, Monday, May 17.

Mr Winfield told Mr Read on the Monday that Bronwyn had left the house around 9.30pm the previous night in an unknown person’s car for a “break” for a few days.

The Office of the DPP initially conveyed the decision to not prosecute in a letter to NSW police on January 10, 2003.

“I wish to advise that after careful consideration of the material referred to him by the coroner and following further investigation, the Director of Public Prosecutions is not satisfied that there is sufficient evidence to lay any charges against Mr Jonathon Winfield at this time,” the letter stated.

Andy and Michelle Read were astonished at the decision and wrote to the DPP asking for more information.

“We are writing to you on behalf of ourselves and the Read family to formally request a full explanation as to why the Crown Prosecutor (Lismore) and the Director of Public Prosecutions (Sydney) have decided that there is not sufficient evidence to lay charges against Mr Jonathon Winfield,” the couple wrote.

“We feel that at the very least we deserve better than a line or two informing us of this decision.

“It has taken 10 long years to get the case to this point and we would appreciate a full written response to this matter at your earliest convenience.

“No doubt you are aware that we are completely dissatisfied at the decision and have already taken steps to investigate the matter further through political and departmental channels.”

Mr Cowdery said in his letter to the Reads in response that Bronwyn’s disappearance “has no doubt caused much grief to you and your family”, and he offered his sympathies.

“My advice to police and the coroner, after very careful consideration of all of the evidence presently available, is that there is not sufficient evidence to charge Jonathon Winfield or any other person,” he wrote.

As DPP, Mr Cowdery found there was enough evidence to charge former champion water polo player Keli Lane with murdering her missing newborn baby, Tegan.

Tegan disappeared shortly after Lane left Auburn Hospital with her in 1996. Lane was convicted of her murder and sentenced to 18 years’ jail in April 2011.

Mr Cowdery resigned as chair of domestic violence prevention charity White Ribbon after being criticised for comments he made about Lane’s sex life on the ABC documentary Exposed.

He told the program he believed Lane was not a threat to the general community because there was no risk she would harm other children.

“She seemed to be a bit of a risk to the virile young male portion of the community. That’s not grounds for putting her in prison, of course,” he said on the program.

Do you know something about this case? Contact Hedley Thomas confidentially at bronwyn@theaustralian.com.au