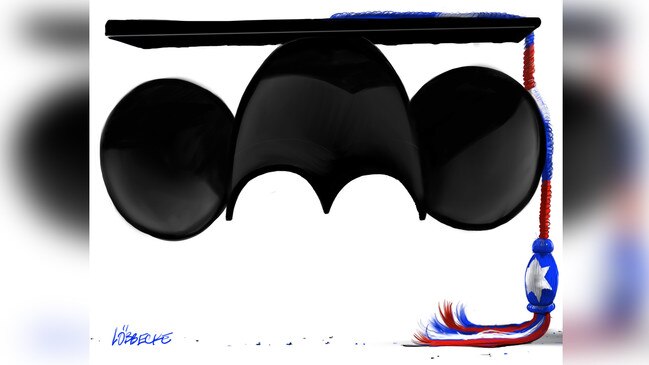

Inquiry-learning fashion has us running in a wheel

When the federal government finally releases the completed Gonski 2.0 Review to Achieve Excellence in Australian Schools, we can expect fine words about making Australian education more evidence-based.

Even so, the extent to which the review will be based on strong evidence remains to be seen — evidence is fuzzy in the postmodern world of education. Importantly, the state of the Australian curriculum is unlikely to feature, despite experts from around the globe coming to the conclusion that curriculum is vital.

The Australian curriculum is light on knowledge. History doesn’t even exist as a distinct subject at the primary level, having been subsumed into something called HASS (humanities and social sciences). The content of HASS is heavy on supposedly generic skills. The knowledge component includes statements such as: “Through studies of their family, familiar people and their own history, students look at evidence of the past, exposing them to an early understanding that the past is different from the present (continuity and change).” In Year 1, rather than gaining knowledge of a civilisation such as ancient China, students learn “how people may have lived differently in the past (empathy)”.

HASS is a textbook example of an “expanding horizons” social studies curriculum of the kind inspired by early 20th-century educational guru John Dewey that had been debunked by academics as early as the 1980s.

Science fares little better, despite Australia being in the grip of a mania for STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths). This contradiction can be resolved when you understand that the STEM craze has little to do with teaching maths and science knowledge to students and everything to do with groovy “makerspaces”, robotics clubs and the doctrine of inquiry learning where students find out things for themselves using their inquiry skills. We have strong evidence from the OECD that a greater use of inquiry learning is associated with decreasing science scores in international assessments, yet this does not stop even the OECD from promoting it.

The science component of the Australian curriculum is divided into three strands: science understanding, science as a human endeavour and the ubiquitous inquiry skills. Examining the science understanding strand, we find bland, vague statements such as “different materials can be combined for a particular purpose”, as if that represents a scientific understanding.

Meanwhile, teacher educators enthusiastically endorse the “general capabilities” of the Australian curriculum such as critical thinking and creativity. This is despite there being little evidence that these capabilities are in any way general, as American professor of psychology Daniel Willingham has written at length. To think critically about something you need to know a lot about it. The same can be said for all of the generic skills and capabilities that the curriculum targets; they all depend on having plenty of relevant knowledge.

Instead of all this we need to build a knowledge-rich curriculum. This would not be an arbitrary list of disconnected facts but would include key concepts that we want students to appreciate and understand. It would include books, paintings and pieces of music that all children would study. The selection of these items rightly would be contentious but we cannot solve that problem by being vague; vagueness just delegates these critical decisions to individual teachers and schools.

Instead, we could appoint a panel that conducts five-yearly reviews of the curriculum with open submissions from the public and interest groups. The final proposals then could be ratified by a committee of federal parliament.

A strong curriculum needs a national assessment system that supports it. We need an early phonics check, such as the one recently trialled in South Australia, to ensure that readers are not lost to literacy early. NAPLAN assessments should continue for years 3, 5, 7 and 9 but the reading and writing components should be embedded in curriculum content.

For instance, if students have been studying the Great Barrier Reef, they could be asked to write an informative piece about it or they could be given something to read about the reef. This would level the playing field dramatically. As it stands, students are presented with pretty random topics. Those from homes that provide a knowledge-rich environment by discussing the news around the dinner table, organising visits to museums and zoos and overseas trips are at an advantage on these assessments.

Assessing the content of the Australian curriculum would have the additional advantage of ensuring that it is taught, but even if we start to assess curriculum content in this way, not all of a school’s curriculum could or should be assessed. Children should play sports, sing, act in plays, paint, go on school trips and engage in experiences that don’t involve a paper and pen.

We therefore need a national agreement about what the right balance should look like and the curriculum panel I have outlined could propose that. It then needs to be enforced. Schools could be audited to check they are providing the right mix and parents could trigger audits if they had concerns. It would not be about judging the quality of provision; it simply would ensure that statutory obligations were being met.

Sadly, none of this is likely to happen, whatever the Gonski 2.0 review proposes. Fashionable ideas such as inquiry learning still dominate the conversation, with the curriculum neglected because of an ideological distrust of knowledge. This harms our students, particularly the most disadvantaged ones, and damages our prospects as a nation.

Greg Ashman is head of research at Ballarat Clarendon College and author of the recent book The Truth about Teaching: An Evidence-Informed Guide for New Teachers.