Donald Trump may have cancelled his summit with Kim Jong-un but he has left the door open for the bridges to be rebuilt between the two leaders.

The president’s bombshell decision to cancel the summit was all but forced on him by a series of broken promises, acts of bad faith and threats by Pyongyang. But the cancellation was not a declaration by Trump that the tenuous rapprochement between the two countries is now over.

Much now depends on how Kim Jong-un reacts to the decision which he may interpret as a loss of face for himself and his regime. If he embarks on a mad Stalinist rant like his Vice Foreign Minister Choe Son Hui did yesterday about US Vice President Mike Pence, then the fragile détente will falter further, at least in the short term.

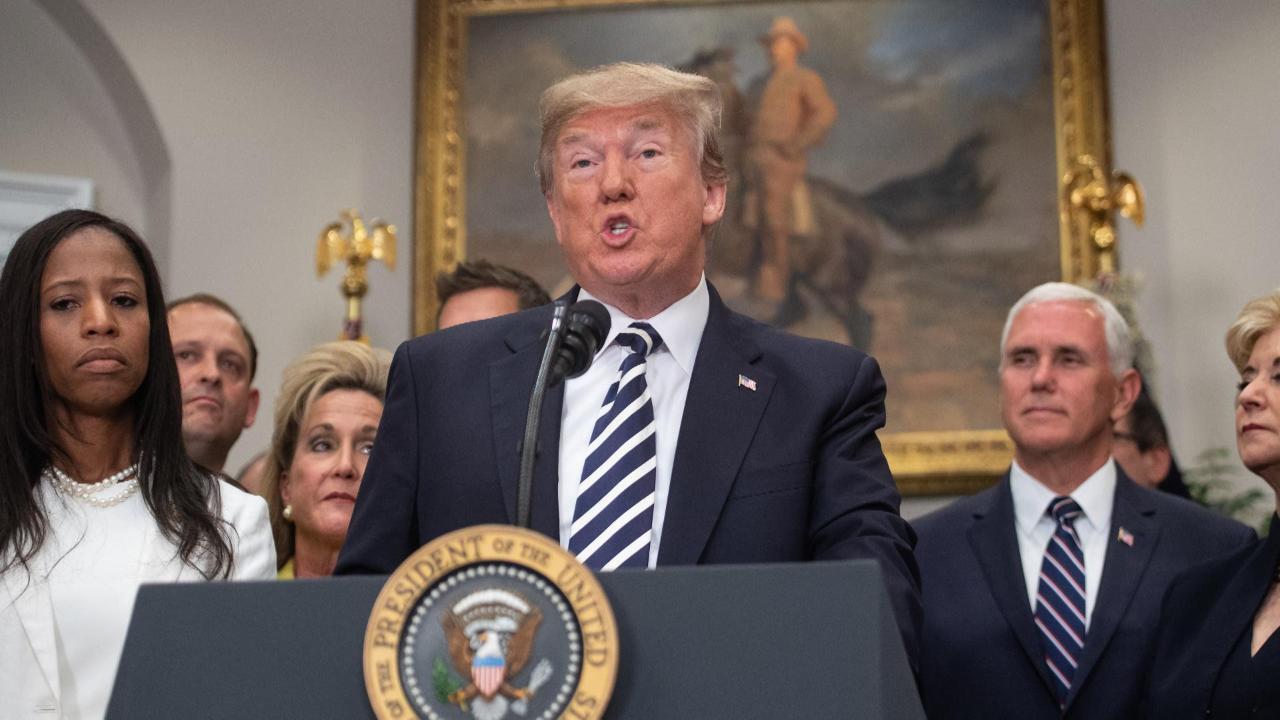

Trump made the decision to cancel this morning after being briefed the previous evening on the comments by Vice Foreign Minister Choe. Choe threatened to cancel the summit, attacking Pence as a ‘political dummy’ and threatening a ‘nuclear to nuclear showdown’ with the US after Pence drew comparisons between the future of North Korea and the fate of Libya.

Trump called in his national security team and declared enough was enough, dictating his open letter to Kim word-for-word.

But Trump’s careful wording of his letter to the North Korean leader makes it clear that the president is still open to a leader’s summit in the future — perhaps even the very near future — if he can be more certain of Kim’s likely behaviour at such a meeting.

Trump, in his letter speaks of the “wonderful dialogue” that was building between himself and Kim and of and how he looks “very much forward to meeting” him.

Trump then he writes “if you change your mind ... please do not hesitate to call me or write.”

The collapse of the summit seemed increasingly inevitable after the events of recent days. Pyongyang overplayed its hand and, in doing so, exposed the large gaps in the expectations of the two nations for the mooted June 12 meeting in Singapore.

North Korea started the rot last week when it overreacted to comments by Trump’s national security adviser John Bolton who spoke of how he saw North Korea following the Libyan model of nuclear disarmament.

Bolton was speaking about the fact that Libyan leader Moammar Gaddafi traded his nascent nuclear weapons program in 2003 for sanction relief. But Pyongyang interpreted the comments as foreshadowing a similar fate for its supreme leader given that Gaddafi ended up being overthrown and killed by rebels in 2011.

Pyongyang threatened to cancel the summit and also declared that the US could not “corner us” and unilaterally declare that North Korea give up its nuclear weapons.

The threat caught the Trump administration by surprise, given that Kim had been making very public moves to improve relations and set the scene for the forthcoming summit. He had halted all nuclear and missile tests, released three US hostages and had promised to close a nuclear test site.

But the threat from Pyongyang unnerved the administration and especially the president.

It also coincided with other strange behaviour by Pyongyang. The White House had sent a team to Singapore to discuss logistics for the summit with a North Korea team but the North Koreans simply didn’t show up. No explanation, nothing.

Then Pyongyang refused to honour an earlier promise to allow international disarmament inspectors to observe their planned closure of the nuclear test site.

Then for an entire week before the attack by Choe, the administration could not make contact with anyone in the regime.

Last weekend Trump understandably became gravely concerned that the summit could backfire without clear outcome. Kim might not even turn up. He reportedly feared it could deliver him one of the most embarrassing moments of his presidency.

Despite Trump’s private concerns, aides say he still hoped the summit would proceed.

At this point the White House appeared to accept that it might have overplayed its hand by demanding that Kim agree immediately to give up all his nuclear weapons for nothing in return. The art of the deal is to give something in return and Pyongyang was now demanding to know what that was.

So Washington started to inject some flexibility into its expectations in the hope of keeping the flaky North Koreans on track for the summit.

Trump spoke of the enormous wealth that would flood North Korea if it agreed to denuclearise the country and sanctions were lifted. He spoke of security guarantees which would ensure that the country would not be invaded and that Kim stayed as the country’s supreme ruler. Trump spoke of unspecified “protections” that would be delivered to Pyongyang amid speculation that the US was willing to sharply reduce the number of troops it had in South Korea.

And finally — in the past 48 hours — both Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pomeo watered down their demand for immediate denuclearisation, stating that the US would accept “credible steps” towards denuclearisation. In other words, North Korea could pursue the progressive dismantling of its nuclear program as sanctions were lifted and the economy was revived.

But then North Korea blew it by overreacting for the second time in a week, this time to the comments made by Pence.

Pence had said: “As the president made clear, this will only end like the Libyan model if Kim Jong-un doesn’t make a deal.”

When asked if this was a threat he said: “Well, I think it’s more of a fact.”

But Pyongyang’s decision yesterday to issue another crazed public rant to these remarks was the straw that broke the back of the White House.

The madness of the rant was rightly too much for Trump to ignore only weeks before he was due to fly across the world to meet Kim.

As Trump pointed out, the cancellation was “a setback for the world” amid hopes that the summit might be the key to ending the most dangerous security threat facing Australia and the world.

Trump deserves credit for getting Kim even close to a position where the two leaders might one day meet to discuss peace.

The president’s hard line rhetoric and refusal to take a backward step towards the rogue regime has helped force China to confront its duplicitous dealings with Pyongyang. Trump has forced Beijing — and the UN Security Council — to apply the toughest sanctions ever imposed on the hermit kingdom.

This was surely a factor in Kim’s abrupt willingness to talk about peace, denuclearisation and to forge a détente with South Korea.

But Trump is correct not to attend a summit until Kim and his regime can behave like grown-ups. Spewing forth comical Stalinist threats of a forthcoming nuclear apocalypse is no way to run a negotiating strategy with the US president.

By cancelling the summit, Trump is telling Kim to grow up and go away until he is ready to do a deal with Washington.

The US has waited almost 70 years for a sane and stable North Korea to emerge and take its place among the community of nations. A bit longer won’t hurt.

Cameron Stewart is also US Contributor for Sky News Australia