QUEENSLAND lost its AAA rating by re-electing an incompetent government that wouldn't control public spending. Now "Kevin from Queensland" is here to help repeat that outcome nationally.

That is not to suggest credit ratings are the gold standard of performance assessment. On the contrary, Kevin Rudd himself repeatedly criticised the rating agencies during and after the global financial crisis. And rightly so, for experience and academic studies show ratings downgrades typically occur long after economic policy is unsustainable.

High ratings are therefore more accurate as a judgment of the past than as an evaluation of the present. But when lost they can bring a significant increase in borrowing costs, while regaining them is no easy task.

Australia's ratings are a case in point. Standard & Poor's downgraded its AAA rating only in late 1986, although fiscal policy had been in deep trouble for the best part of a decade. It then took until October 2002 to regain a AAA from Moody's, with S&P following suit in February 2003 and Fitch indicating an upgrade to AAA was in prospect.

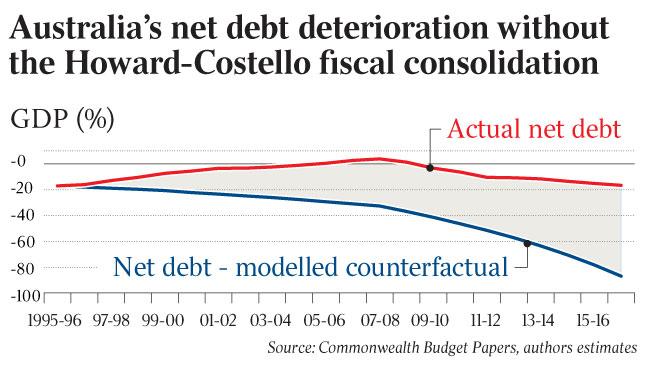

Years of disciplined fiscal policy under John Howard and Peter Costello were needed to secure those upgrades. The overall extent of the fiscal turnaround they achieved can be seen from the graph. It compares fiscal outcomes under Howard and Costello with those that would have occurred had they simply behaved like their predecessors. (Details of the statistical method are on my blog.)

The results are stark: despite strong growth from 1996 on, Rudd would have inherited a net debt of $380 billion, or 32 per cent of gross domestic product, without the Howard-Costello change in fiscal policy stance. Adding Rudd's deficits to that, net debt would now be 59 per cent of GDP, rising by 2014-15 to 66 per cent of GDP or more than $40,000 a person. That is a level worthy of the Eurobasket. Of course, given his inheritance from the Howard years, not even Rudd could get us into Eurobasket shape quickly - although a budget bottom line that deteriorates by $1bn a week, as happened from Wayne Swan's 2013-14 budget to last week's economic statement, would certainly do the trick. But merely because we are still below the debt levels that trigger downgrades should not be a source of comfort.

After all, ratings agencies focus on solvency, not efficiency: on whether debt can be repaid, not whether it is desirable. If there is sufficient scope to cut spending and increase taxes, their requirements will be met. But that one can starve the kids to pay off the card is hardly an argument for pushing the credit limit to the maximum. And the higher the economic and social costs of hiking taxes and slashing expenditure, the greater the risks of allowing debt to accumulate.

That is especially true for an economy extremely exposed to commodity price cycles. In every decade since the 1960s, Australia's terms-of-trade variability has been more than twice the average for the high-income countries. And since 2007 the variability of our terms of trade may have trebled, or on some estimates even quadrupled, compared with the preceding decade.

Having the fiscal scope to absorb shocks of that magnitude requires net debt that over the economic cycle averages close to zero - and that, when the cycle is at its peak, is solidly in the black.

But although commodity prices and the terms of trade have only recently recorded historic highs, net debt is back to the levels it reached under Paul Keating. And with prices and the terms of trade declining, the budget position is not reassuring: according to the economic statement, the next two years will see a cumulative cash deficit of more than $54bn. To make matters worse, spending growth has accelerated, and with myriad policies still uncosted, the promised return to surplus is difficult to believe.

The parallels to Anna Bligh's disastrous fiscal strategy are striking. Adjusting for inflation, Queensland public spending growth averaged 6.6 per cent annually from 2004-05 to the change in government. With receipts rising by only half that, the result was a near trebling in net debt. And rather than being invested in productive assets, much of that debt was used to fund white elephant infrastructure projects, with losses comparable to those expected on Rudd's National Broadband Network, and pay for increases in public sector salary bills.

Little wonder Campbell Newman sharply reversed course, narrowly avoiding the train wreck ahead.

And little wonder Newman has become Rudd's whipping boy. Rudd once claimed to be a "fiscal conservative". With the commonwealth's ratio of net debt to GDP already higher than that for NSW and rapidly approaching that for Queensland, his record makes it obvious he is anything but.

True, he hasn't yet lost us our AAA rating; but he will if he can, and once we get to that point, the road back will be painful indeed.