ACCORDING to Kevin Rudd, with "the China resources boom over, we need to aim for a productivity number with a '2' in front of it."

In fact, keeping real incomes per head rising as rapidly as they have in the last two decades requires annual labour productivity growth of at least 2.5 to 3 per cent, more than twice the average since the late 1990s.

But Rudd is unlikely to help that happen. For although he now promises "a new approach to the regulatory impost on business", it was Rudd who set the pace in Labor's regulation explosion.

No indicator highlights that better than the exemptions he granted from Regulation Impact Statements, a process which tests regulations for cost-effectiveness. Under Howard, there were four exemptions; in just two years and seven months, Rudd granted 31. And Gillard then did nothing to stem the tide, cracking the century in March this year.

What few resource projects remain will be the victims of that regulatory avalanche. Those projects' viability is finely-poised; minor changes could make them uneconomic.

Yet Rudd's first decision on returning to the prime ministership was to restrict 457 visas, greatly increasing those projects' costs. Nor has Rudd stopped there.

A 2009 Productivity Commission survey found more than 150 statutes governing resource ventures, administered by more than 50 agencies at the national, state and territory level. With these overlapping, about 80 per cent of projects suffer from commonwealth environmental requirements that lead to no improvement whatsoever in environmental outcomes.

But after Rudd stated that "we should aim at having one single integrated environmental assessment system", his new environment minister promptly resiled from that commitment, apparently with Rudd's support.

The signal to investors could scarcely be clearer: Mr Chaos is here again. But it is not only new resource projects that Rudd's penchant for poorly judged regulation threatens. Rather, it is our overall ability to prosper as the resource boom wanes.

After all, a crucial feature of the boom has been the dramatic growth in the economy's asset base, with capital per hour worked in the market sector rising by more than 40 per cent since 2003. As export prices fall, it is how much extra output we squeeze from each dollar of that capital stock that will determine growth in productivity and real incomes.

But as in previous resource booms, it is once the boom ends that productivity-sapping industrial relations regulations will really bite. That is unsurprising: during the boom, increasing output is so profitable that union bloody-mindedness mainly affects the distribution of the gains, rather than their magnitude. But as normality returns, the windfall profits that could absorb restrictive work practices disappear. The toll IR regulations inflict in poorly used plant and equipment then mounts, and lost jobs too.

Yet Rudd, who signed the Fair Work Act's exemption from regulation review, shows no willingness to address that harm; and his other policies will only compound the productivity losses.

That is as true of his emissions trading scheme as it was of Gillard's carbon tax. Rudd argues the shift to the ETS will cut permit prices to European levels, greatly reducing the scheme's cost to industry. But that claim makes little sense.

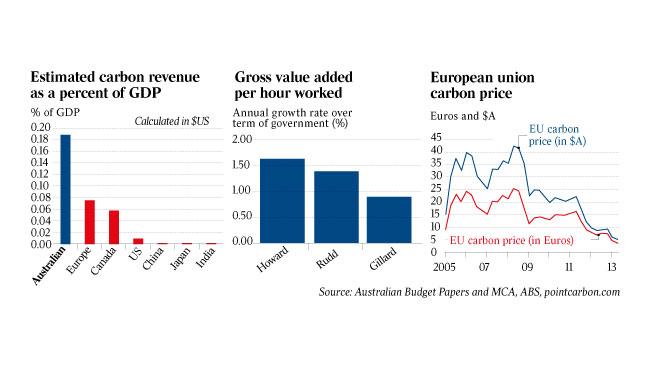

Yes, permit prices would align with those in Europe were Australian emitters allowed to purchase all their permits from the EU scheme; but they won't be. Rather, at least half their emissions must be covered by Australian permits. And the number of Australian permits made available will be determined by emissions caps currently being reviewed by the Climate Change Authority; if only a few are issued, scarcity will drive their price above those in EU.

But even were Rudd's claim correct, our scheme's wide coverage and relatively small number of free permits means its costs would still be far greater than those of any scheme overseas. Aggravating the pain, EU permit prices are extremely volatile, fluctuating more than twice as much as prices on the London stock exchange.

Moreover, because the Australian dollar weakens when our economy slows, the $A cost of European permits rises in tough times, increasing the risks Australian producers face. That future prices will depend on European decisions over which we have absolutely no control only makes those risks greater.

What Rudd has not explained is why those costs and risks are worth bearing. Treasury's modelling suggests that at current EU permit prices, there will be virtually no emissions reduction in Australia; how much our purchase of permits will reduce emissions in Europe, which is drowning in permits, is questionable at best. Rudd's scheme is therefore little more than a nuisance tax: with the added disadvantage of transferring revenues that would otherwise have accrued to the Australian government to the EU, while imposing substantial inefficiencies along the way.

But none of those niceties will slow Rudd for a moment. He may talk the productivity talk; but the only walk he is interested in is that which keeps him in The Lodge. If that requires trashing our competitiveness, so be it; and should his strategy succeed, Labor's Faustian bargain with Rudd, making him almost impossible to remove, means he will be uniquely powerful, facing few constraints on the harm he can impose.

With so much at stake, Tony Abbott needs to show every bit as much willingness as Rudd has to reconsider policies that may tell against him; fighting Rudd is no time for Queensberry rules. Otherwise, our prospects for prosperity after the resource boom are bleak indeed. And no amount of rhetoric from Rudd will alter that.