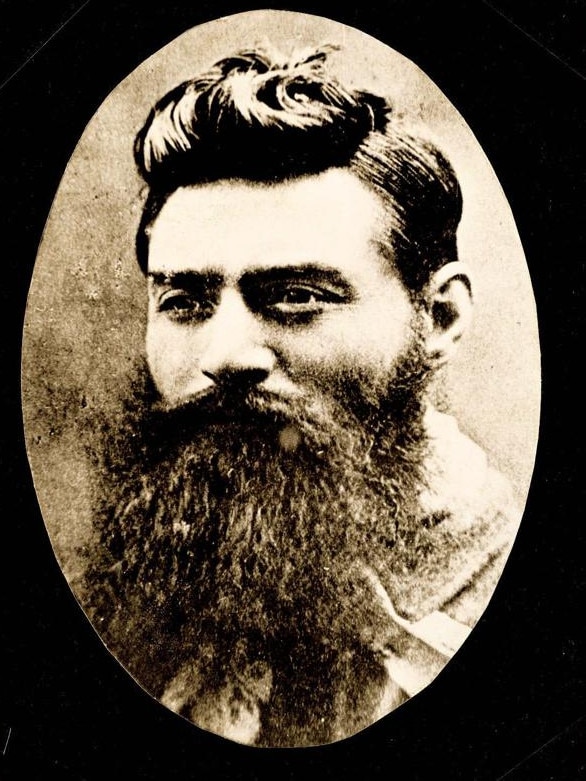

Yet another Ned Kelly film? The so-called True History of the Kelly Gang, based on the novel of the same name by Peter Carey, is in production. No doubt you already know the story of Australia’s favourite son. Harassed by the colonial police, this heroic Irish-Australian was a nineteenth-century Robin Hood who fought against the British oppressors and the greedy banks. He used lethal force, but only against those who would have killed him first. A champion of Victoria’s downtrodden selectors, ‘Our Ned’ personified mateship, egalitarianism, and the larrikin streak. Right?

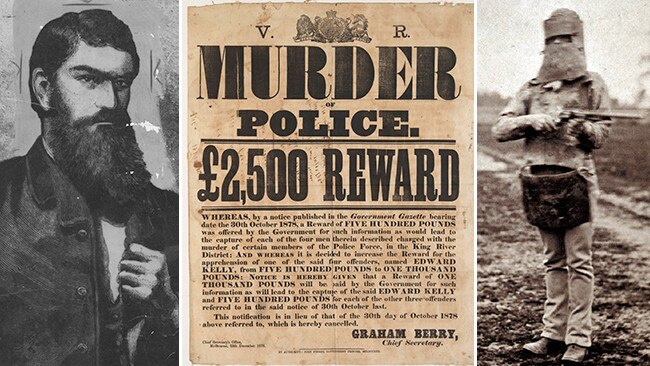

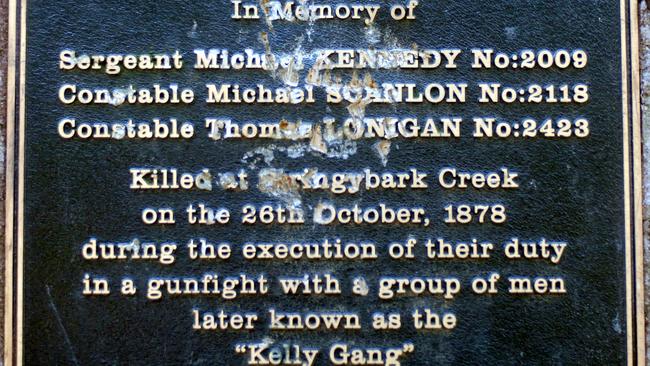

Wrong. Contrary to the apologist tosh you will read in many of the numerous Kelly biographies, he was a ruthless, self-aggrandising murderer and a parasite who stole from both rich and poor. Like many a narcissist, he had an entrenched sense of entitlement and victimhood, and was a pathological liar. To write admiringly of this cop-killer is to sully the reputations of the three brave officers who the Kelly Gang murdered at Stringybark Creek in 1878 — Sergeant Michael Kennedy, Constable Michael Scanlan, and Constable Thomas Lonigan.

One of those who was never taken by the legend is filmmaker Ben Head. As a child, he often wondered why we idolised Kelly. Now the 19-year-old Victorian College of the Arts student is producing a short film Stringybark, which is based on the perspective of the three murdered officers and the sole survivor, Constable Thomas McIntyre. Unlike the other films portraying Kelly, Head’s will be adhering to the facts as uncovered by research.

Filming will begin in late September, and already the project has attracted much support. Only a day after Fairfax ran an article this month about the proposed production and Head’s appeal for crowd funding he secured an additional $10,000, and is close to his target of $21,000. He intends using the short film of around 35 minutes to request agencies such as Screen Australia to provide funding for a full length movie.

Could the surge in donations for Head’s film be a sign many Australians are cheesed-off with the mythologising of Kelly? Head certainly is encouraged. “The response I’ve received so far is astounding,” the young writer and director told me this week. As someone who has read widely about the Kelly saga and deplores the partisan history, I am pleased to hear that. Head’s project has already upset the keepers of the Kelly flame, who become outraged when someone besmirches their idol.

So just to stir them up a little more — and for the benefit of those who were taught the romanticised version of the Kelly history — I will scrutinise some of the popular accounts.

The catalyst for the formation of the Kelly Gang was the outlaw’s attempted murder of Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick in April 1878. Fitzpatrick had gone to the Kelly household alone — a foolhardy act — to arrest the outlaw’s younger brother Dan. You were probably taught Fitzpatrick made sexual advances towards Kelly’s 15 year old sister, Kate, and that his shooting was an act of reprisal. But when a journalist put this rumour to Kelly through his lawyer after his capture in 1880. Kelly strongly denied Fitzpatrick had acted so, saying it was a “foolish story”.

Kelly’s mother, Ellen, who joined in the attack and was later tried, was sentenced to three years imprisonment. The judge who presided at her trial, Sir Redmond Barry, was the same one who later sentenced Kelly to be hanged. In his gushing biography Ned Kelly: The Story of Australia’s Most Notorious Legend, Peter FitzSimons repeats the popular account that Barry said to Ellen “If your son Ned was standing by you in the dock I would give him 21 years.” If said, this would be a sound argument that Barry should not have presided at Kelly’s trial due to apprehended bias. In all likelihood, it was made up. Ellen’s trial attracted considerable press coverage, yet not one of the newspapers made mention of Barry’s purported remark.

In October 1878 a police party of four led by Sergeant Kennedy was tasked with capturing the Kelly brothers. Making camp at Stringybark, McIntyre and Lonigan stayed there while Kennedy and Scanlan went off searching. The gang ambushed the camp, killing Lonigan and capturing McIntyre. When the other two officers returned hours later, the gang fired on them, killing Scanlan. McIntyre escaped during the firefight.

As for Kennedy, the circumstances of his death are unclear. Popular account has it he was mortally wounded in combat, and that a merciful Kelly administered the coup de grâce. The likelihood of what really happened is far more chilling.

In the period between the ambushes at Stringybark and the discovery of Kennedy’s body days later, a friend of Kelly, Isaiah Wright, publicly declared his belief the outlaw would torture Kennedy. When the body was found, the right ear of the corpse was detached. FitzSimons declares definitively “The parts of Kennedy that are missing have been nibbled off by animals.”

How could he be sure? The Argus reported in June 1880 rumours in the district that “Kennedy was but wounded on the day of the encounter, and was allowed to live all night, so that the gang might learn from him how to work his Spencer rifle. On the following morning Ned Kelly shot him through the breast.” The horrific possibility that Kennedy was tortured cannot be discounted.

But were not the shootings at Stringybark justified on the basis the police intended not to capture the Kelly brothers, but to kill them? The Kelly apologists stridently assert this was a police vendetta, but there is no credible evidence to support this argument. Kennedy, a father of five, was an honest and decent man with an impeccable record. The fact that police were armed with a borrowed rifle and extra ammunition is often mentioned to imply sinister motives, but their actions made perfect sense. If you were preparing to defend yourself against armed felons who had shot a police officer, you would be a fool to rely solely on a revolver.

According to FitzSimons, the police party provisions included “two long leather straps, specifically designed and made by the Mansfield saddler Charles Boles so that a pair of dead bodies could be easily suspended from them”. Yet there is no contemporary record of this supposed acquisition. Dr Robert Haldane, a historian and former Victoria police superintendent states “This fanciful notion often cited to support the idea that the police were ‘trigger happy’ and ‘ready to use their guns’, thereby justifying a pre-emptive attack by the Kellys, is mere supposition based on hearsay that first surfaced well into the 20th century.” What cannot be disputed is that the police party were carrying handcuffs at the time they were ambushed. Does that not indicate the police’s intention to bring back live bodies?

In the 1881 Royal Commission into the Victoria Police, a witness, Patrick Quin, gave evidence of a conversation he had with Kelly around the time of the Fitzpatrick affair. Quin urged Kelly to give himself up to police, but the latter replied “No; if any man interferes with me I will shoot him.” This is clear and first-hand evidence that Kelly, six months prior to the Stringybark massacre, was prepared to kill to avoid arrest. How often do you see the pro-Kelly authors addressing this or even mentioning it for that matter?

There is also the theory the actions of the Kelly should be mitigated or even excused in the context of British oppression of the Irish. If you think so, consider this. Justice Barry was Irish-born, as were all four police at Stringybark. Two of them, Kennedy and Scanlan, were Catholics, as was Kelly. At the time of Kelly’s death two Irish-born Catholics, John O’Shanassy and Charles Gavan Duffy, had served as Premier of Victoria.

Another furphy is the assertion that more than 32,000 Victorians signed a petition demanding clemency for Kelly. The Sydney Morning Herald noted of the petitions “they were signed principally in pencil and by illiterate people, whilst whole pages were evidently written by one person”. Lastly, the royal commission — while censorious of police incompetence in the Kelly affair — found “no evidence had been adduced to support the allegation that either the outlaws or their friends were subjected to persecution or unnecessary annoyance at the hands of the police”.

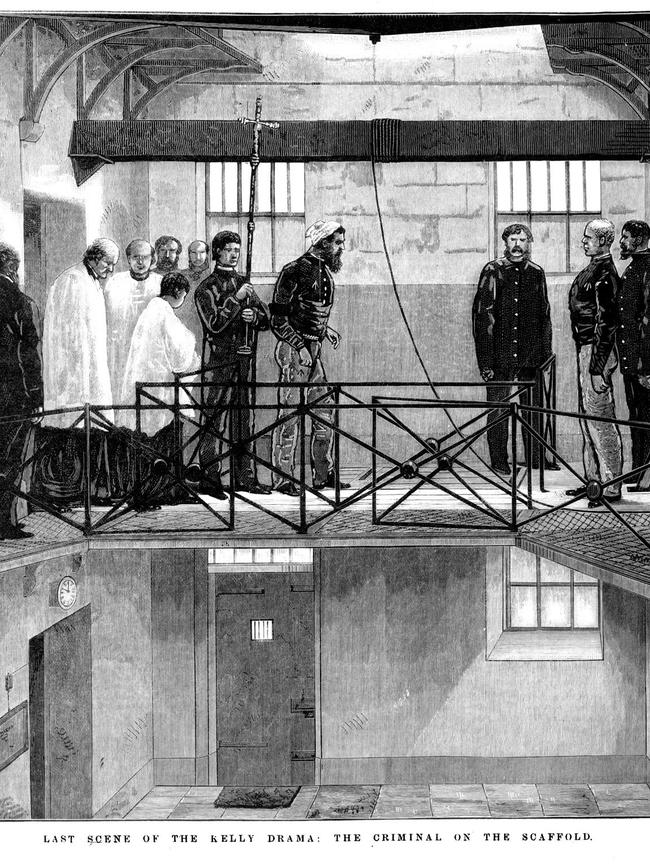

As for Head, more power to him for being sceptical of the Kelly orthodoxy and telling the story from the perspective of the fallen officers. In time, his biggest challenge could well be refuting all the Kelly myths in one feature film, for there is so much misinformation and outright falsehoods. The outlaw’s apologists and devotees will be apoplectic with anger, but they should learn to temper this with Kelly’s apocryphal gallows lament “Such is life”.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout