CORRUPTION, the economist Robert Klitgaard once said, is the inevitable product of "rents plus discretion minus accountability". He had the gangsters running equatorial Africa in mind; but if the allegations being presented to the Independent Commission Against Corruption are proven, he could have been writing about the government led by Kristina Keneally in NSW.

Yet Keneally, who described Joe Tripodi and Eddie Obeid as mentors, was the symptom, not the cause of the underlying forces at work. And the gangrenous allegations aired at ICAC have origins that reach far beyond the sordid politics of Sussex Street.

At the heart of the allegations being investigated by ICAC are favours claimed to have been granted by Labor ministers to their mates.

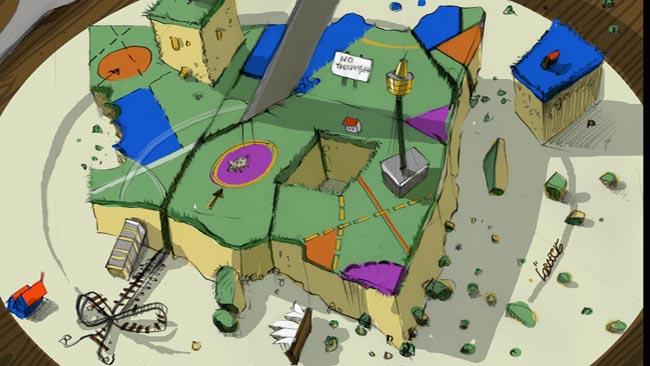

Ministers were in a position to dole those favours out because state planning and licensing laws gave them monopolies over scarce resources, most notably the use of land. And successive changes to those laws, from when Labor came to power in 1995 until it lost office last year, made the resources ministers could allocate more valuable while steadily weakening the controls over how their discretion was exercised.

Not that the difficulties started in 1995. Rather, as the evolution of NSW's zoning laws shows, the problems stretch back to 1945 when, imbued with the zeal of postwar reconstruction, William McKell amended the local government legislation to strengthen planning powers, with planning responsibilities for the Sydney area divided between the newly established Cumberland County Council, covering the bulk of the metropolitan region, and the City of Sydney itself.

Cumberland's regional plan of 1948 was the highwater mark of utopian urbanism in Australia, providing a vast "green belt" around the city itself, intended to prevent "promiscuous urbanisation" and thus "bring fresh air and unspoiled countryside to as many urban-dwellers as possible".

But the stringent controls over development in Cumberland were not matched by any rational system of land allocation within Sydney itself. Rather, all decisions of any consequence were made by alderman, later lord mayor, Paddy Hill and the "Irish mafia" that ran the Redfern ALP.

In the reshuffle that followed the death of Joe Cahill, Hill emerged as minister for local government, with the one objective of dramatically expanding public housing (and the patronage opportunities it provided).

Unfortunately, the green belt was the readiest source of developable land.

To that impediment, Hill had a characteristically straightforward solution. "F..k the green belt", he told journalists in a Sydney pub, "I want developers to start before the next election".

Good as his word, two days before Christmas 1959, Hill eliminated two-thirds of the green belt and gave himself power over most of the area now opened to construction. And as Hill had already begun to use the state's newly passed Height of Buildings legislation to control development in Sydney's CBD, the minister emerged as the pivot in the allocation of land.

Not that the Askin government, elected in 1965, turned back the clock. With the great Sydney building boom of the 1960s getting into swing, the Sydney Council had made a hash of planning and, in any event, Askin regarded the opportunity to use urban development to "clear the Labor voters out of Woolloomooloo" too good to miss.

While Askin's 1967 dismissal and subsequent restructuring of the council did make it a somewhat more competent organisation, it strengthened the practice of concentrating major decisions in the minister. And a further decisive move in that direction was made under Neville Wran, who having opined in 1976 that the Sydney City Council had "no more power than a crippled praying mantis", ensured the 1979 Environmental Planning and Assessment Act made virtually every aspect of land use in NSW "subject to the direction and control of the minister".

Labor's changes to that legislation in 2005, which created a special, completely discretionary, regime for projects of "state or regional significance", and in 2008, restricting residents' rights to object to development, were merely the final step in taking ministerial power to unfettered heights.

All this had the potential to feed corruption. But there were two further factors that could transform everyday peculation into rampant kleptocracy.

The first was Bob Carr's decision to shut down Sydney's expansion. Releases of developable land declined to about one-third the levels in Melbourne, with a far higher share of what land there was being reserved for large projects. With monopoly restrictions on supply, the result was to increase all land values, and especially those closest to the city, which rose to 16 times those for the suburbs furthest from the CBD.

That artificial scarcity made the gains from favourable land use decisions enormous, with values quadrupling when land was rezoned from low density to mixed use. And similar effects occurred for mining leases, as the combined impact of tighter restrictions on land use and increased coal prices transformed routine licensing decisions into a matter of billions.

Little wonder planning matters came to account for about a quarter of ICAC's caseload. And little wonder developers and project proponents came to contribute so greatly to a spectacular 70 per cent rise in Labor's spending on NSW election campaigns over the period 1999-2007.

But a second factor aggravated this business model's toxic potential. With the end of the Cold War, Labor's factions, which until then had at least the pretense of ideological differences, degenerated into machines for rewarding factional loyalty. As a party without a future became the creature of factions without ideas, a culture of "anything goes" set in, made all the more urgent, in the Keneally government, by the looming threat of defeat. And when that defeat came, Keneally left office controversially nullifying, in her final moments of power, court action against the contentious Barangaroo redevelopment.

It is now the O'Farrell government's job to clear up the mess Labor left, not least a dysfunctional system for managing land use. It has made sensible steps in that direction, including placing more effective disciplines on ministerial powers. But it needs to heed the wisdom of that greatest of reformers, Edmund Burke, as should Tony Abbott.

Implacably opposed to the "Old Corruption", Burke argued that only "economical reform" - the repeal of the government monopolies, special privileges and sinecures that form the stuff of tainted deals - could ever eliminate venality from public life.

From the unions, which Labor treats as above the law, to taxis, that challenge remains. Until it is dealt with, the problems will persist, and all their risks with them.