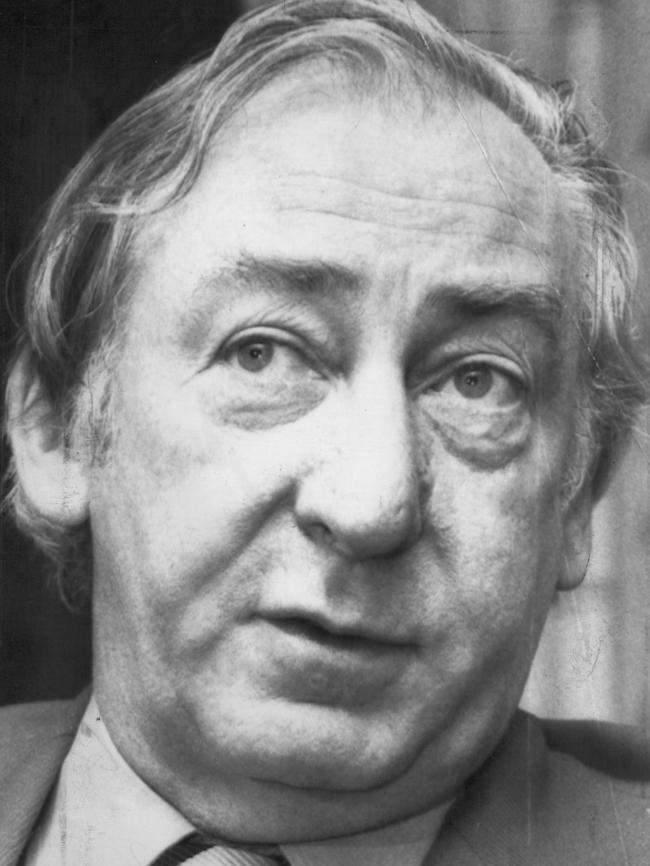

For lovers of political scandals and judicial intrigue, it is the exposé of the decade. For the many strident defenders of the late Lionel Murphy, it could well be an iconoclastic catastrophe.

Last week, federal parliament’s presiding officers announced they would next month release all documents relating to the conduct of the former High Court judge and Whitlam Government attorney-general.

In July 1985, Murphy faced trial for two charges of attempting to pervert the course of justice in relation to a criminal prosecution against a longstanding friend and Sydney solicitor Morgan Ryan. It was alleged he improperly attempted to influence NSW District Court judge Paul Flannery and NSW chief magistrate Clarrie Briese. At the time of Murphy’s intervention, Ryan was facing a conspiracy charge for allegedly trying to obtain by unlawful means permanent residence status for a number of Korean nationals.

Murphy was acquitted of the charge that he attempted to pervert the course of justice in relation to his dealings with Flannery. However, the jury found him guilty in respect to the Briese matter. Murphy successfully appealed and was retried in April 1986 for the allegation involving Briese. This time a jury found him not guilty.

Following Murphy’s acquittal former attorney-general and then Hawke Government minister Gareth Evans, made what could be politely termed a brave announcement. “The allegations against Justice Murphy”, he said, “have been dealt with comprehensively, fairly and finally by the criminal courts.”

Within days of Evans’s proclamation, the Hawke Government, stung by the Stewart Royal Commission’s announcement that there were additional allegations against Murphy, was forced to legislate a commission of inquiry comprising three retired judges to advise whether Murphy’s conduct amounted to “misbehaviour” as per section 72 of the Constitution.

From its beginning, this commission was faced with considerable impediments. It could not, for example, make any finding unless the relevant evidence would be admissible in a proceedings in court, which belied its ostensibly inquisitorial nature. Neither, unless the commission believed there was a prima facie case of misbehaviour, could it compel Murphy to give evidence. The government refused the commission’s request for federal police assistance, instead providing it with investigators from the Australian Capital Territory Corporate Affairs Commission.

Controversially, the commission was specifically excluded from considering “issues dealt with” in Murphy’s trials of July 1985 and April 1986. In having framed these narrow terms of reference so, the government was maintaining attorney-general Lionel Bowen’s assertion that the not guilty verdicts in Murphy’s trials had removed “any suggestions of taint” in respect to the charges. This rationale was fallacious. “Misbehaviour”, as provided in the Constitution for removal of a High Court judge, implied conduct which rendered one unfit for judicial office, not just conduct confined to criminal acts.

Murphy strongly denied attempting to improperly influence Flannery and Briese. However, there were certain facts not in issue that gave rise to judicial impropriety and conflict of interest on Murphy’s behalf. He did not, for instance, dispute he had made inquiries of Briese with respect to Ryan’s committal proceedings, or that he’d expressed disappointment when told by Briese that the presiding magistrate, Kevin Jones, would probably commit Ryan’s matter for trial. Nor did he deny ringing NSW Chief District Court judge James Staunton to urge that Ryan be given an expedited trial.

Likewise, it was not disputed that Murphy had invited Flannery for a private dinner at his residence two days before the latter presided over Ryan’s trial in July 1983, despite the two judges never having socialised with each other in their 30 year acquaintance. Neither was it contested that Murphy, at that engagement, had suggested Flannery read the former’s dissenting judgment relating to a conspiracy matter. Murphy later claimed at his trial that he was unaware Flannery would be presiding over Ryan’s trial.

“It would be unfortunate if Parliament or the public were to gain the impression that it was expected or normal judicial behaviour”, observed retired judge Xavier Connor, who in 1984 had assisted a Senate committee to examine the allegations against Murphy. Yet the terms of reference did not allow for the commission of inquiry (as opposed to the Senate committee) to consider any of these matters, despite them being highly relevant to the question of whether Murphy’s actions amounted to “misbehaviour.”

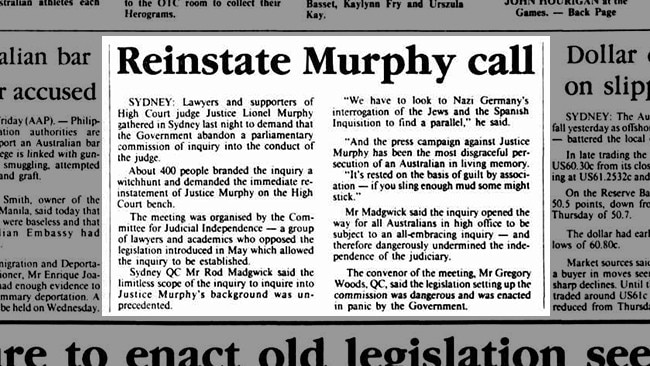

Nonetheless the commission pressed on in accordance with its charter. In July 1986 it put to Murphy fourteen specific allegations concerning his behaviour. That same month, Murphy’s supporters, including politicians, lawyers and academics, protested that the commission of inquiry was an usurpation of judicial independence. “We have to look at Nazi Germany’s interrogation of the Jews and the Spanish Inquisition to find a parallel,” declared Sydney QC and later Federal Court judge Rod Madgwick.

In late July 1986, while the commission was still in progress, Murphy revealed he had inoperable cancer. Much to the disapproval of High Court chief justice Sir Harry Gibbs, Murphy returned to the bench on August 1, having been absent for nearly 22 months.

Only weeks after Murphy’s return, the government announced that as a result of Murphy’s terminal illness, it would legislate to terminate the commission and permanently seal all records relating to it. The 30-year embargo was introduced later only as a means to have the Senate pass the legislation. Acting attorney-general Evans also announced that the government would make a “substantial ex gratia payment” towards the cost of Murphy’s legal fees incurred in defending the criminal matters. This payment, it was later revealed, was approximately $420,000.

Murphy died on 21 October 1986. For those in the Hawke Government, the sense of mourning must have been accompanied by a tinge of relief at his untimely passing. Had he survived and the commission advised that his conduct amounted to misbehaviour, it would still have ultimately fallen to Parliament to decide Murphy’s fate — a debate that would have torn Labor asunder, given the party left’s fanatical support for him.

Even when Murphy was originally found guilty of attempting to influence Briese, and prior to the verdict being overturned, there was little sign of the party distancing itself from its controversial defendant. The verdict, said former Whitlam Government treasurer Dr Jim Cairns, was “Cruel, inhuman and lacking in commonsense.”

Even senior government members threw discretion to the wind. “There is nothing unusual in professional people talking about professional matters” said Hawke Government minister Arthur Gietzelt in a euphemistic attempt to explain Murphy’s approach to Briese. “I frankly don’t believe he did what he has been found guilty of”, said foreign affairs minister Bill Hayden. That senior government ministers would make such comments before legal avenues of appeal had been exhausted was disquieting. Yet it was nothing compared with remarks made by Murphy’s old friend and then NSW premier Neville Wran QC.

In November 1985, upon learning that Murphy had secured a retrial, Wran told a journalist he had “a very deep conviction that Justice Murphy is innocent of any wrongdoing.” His remarks were given wide publicity, and in December 1986, the NSW Court of Appeal ruled Wran was in contempt, finding that his remarks were a “calculated and deliberate abuse of power” and could have prejudiced Murphy’s retrial.

In 1999, it was revealed that former NSW Land and Environment Court chief judge and Whitlam Government minister Jim McClelland had privately admitted to perjuring himself in giving character evidence at Murphy’s trials. Crucially, McClelland also failed to disclose in his evidence a number of phone conversations he had with Murphy that led him to believe he was improperly attempting to influence Staunton (who at that time had been allocated the Ryan matter).

It is often said in defence of Murphy that his return to the bench, despite the unresolved allegations, was indicative of his work ethic, and his commitment to the law and the upholding of judicial independence. Conversely, his critics have argued that his failure to resign and his dogged insistence on returning threatened to compromise the High Court, and that only his premature death ended what potentially could have been the nation’s biggest political and constitutional crisis.

Whatever it was that drove Murphy until the very end is a question others can decide. But a prescient observation by then The Age journalist Michelle Grattan in February 1975 — following the announcement that Murphy would be appointed to the High Court — may help in that decision. Murphy, she observed, “has a streak of impetuousness, recklessness and self-centredness, and a capacity for political intrigue, which led him to be responsible for some of the Government’s greatest blunders.”

As for the impending release of the commission documentation, we can expect it will prove interesting reading, especially if contains transcripts relating to the illegal interceptions of Ryan’s phone by NSW police in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Ryan had mixed with various colourful identities in Sydney, including Abe Saffron and Murray Farquhar, the former NSW chairman of the bench of stipendiary magistrates, who was jailed in 1985 for attempting to pervert the course of justice. Needless to say, Ryan had numerous telephone conversations with Murphy.

By all means look forward to July 24 and the release of the commission documentation. But in reality, we have had for many years all sufficient information at hand to make an informed judgment about this affair — not just about Murphy but also of those who protected his reputation, both in his life and death.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout