IMAGINE what would happen if pro-meat campaigners staked out a vegan commune and waited until the simple creatures were tucked up in their koala-suit peejays before bursting through the door with the cameras rolling.

Picture the startled tofu munchers with the lights in their faces, blinking, squealing and thrashing around in the air.

They would look something like Ean Pollard's pigs in an 8 1/2-minute clip posted on YouTube. Mr Pollard told The Land last week that animal rights vigilantes had broken into his piggery near Young, NSW, in the early hours of the morning. "The sows have got up thinking they're going to get fed, but they've become agitated because there's no feed - only people running around with flashlights, filming."

Let us hope Joe Ludwig doesn't Google this stuff, or he'll shut the industry down in a flash. Pig producers would be in the same sorry mess as the Brahman breeders in the north, caught like the meat in the sandwich between animal welfare campaigners and a weak-kneed government, while the price of cheese and ham croissants goes through the roof.

Animal activists and YouTube make dangerous partners, promulgating videos that are big on hand-held horror but devoid of context. There is no acknowledgement that pigs naturally get toey if they are woken in the night and think it might be tucker time. Nor is it mentioned that the industry is investing heavily to voluntarily phase out sow stalls by 2017, in keeping with practices in Europe and New Zealand.

Animal Liberation's Mark Pearson claims Mr Pollard's pigs were "desperate and hungry" before the friends of the four-legged broke in. Really? Might Mr Pearson care to speculate on a farmer's motive to starve his livestock? The pig farming business model is pretty simple really: breed them, fatten them and send them off to market as cleanly and efficiently as possible.

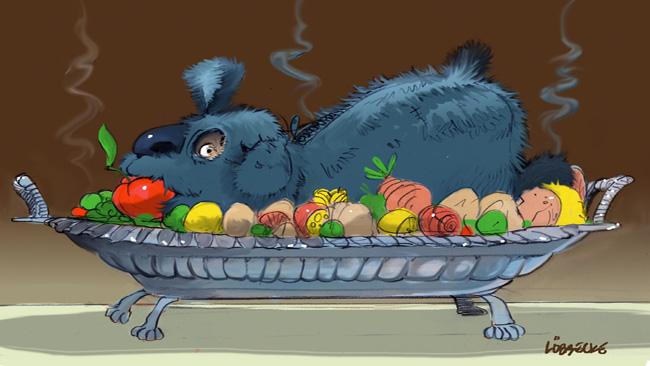

Clever livestock farmers are stress management experts dedicated to spreading Jeremy Bentham's greatest-happiness principle to animals as well as humans: "Create all the happiness you are able to create; remove all the misery you are able to remove." The aim is to keep the animal's life serene from conception to slaughter, maximising the production of healthy, tender meat. Quiet handling in the final hours of a pig's life is particularly crucial. Severe stress during transport, off-loading or in handling pens leads to the rapid breakdown of muscle glycogen. The meat has a shorter shelf-life; it is pale, acidic and virtually unpalatable.

Whatever the animal vigilantes may tell you, factory farmers are not, by and large, tormenters who derive a sadistic thrill from watching dumb animals suffer. They are entrepreneurs running small, lean businesses working to tight margins, for whom a happy pig equals profits and sick ones equal loss. The last thing the farmer wants to do is to set the pigs' adrenal glands racing, which is what happens, for instance, when someone comes bursting in unexpectedly in the middle of the night. When mammals get stressed and hydrocortisone is released into the body, it plays havoc with the metabolism. Blood sugar levels go shooting up and fat gets burned. Feed costs go up, the pig's weight goes down, pigs stop breeding and the business model is kaput.

No farmer with an eye on the bottom line would beat a pig or condone rough transportation. Bruised meat is wasted meat and damaged hides are worthless. Market forces are the pig's best friend.

Instinctively, we would be less troubled if the pigs could roam around and forage a little, and perhaps roll around in mud. Whether pigs in such conditions would be more or less content is a matter of contention. In the absence of reliable porcine attitude surveys, we can only go by the empirical evidence of health and death rates.

Roaming pigs are more likely to suffer heat stress, fall victim to pathogens or suffer bullying. Food and water supplies are less reliable and the weak are obliged to fight the strong. Besides, if the aim is to get easy-carve pork roast through the checkout at less than $10 a kilo, pigs will have to be reared indoors. Those who prefer the taste of free-range pork or the thrill of virtue that comes with its purchase have other, more expensive options.

These are challenging times for the domestic pork industry. Pork imports were negligible 20 years ago; now overseas pork producers have a third of the Australian market. Most of that meat comes from Denmark, Canada and the US, the world leaders in intensive pig farming.

The strong dollar has eroded export markets, grain prices have risen sharply and the big supermarkets are driving harder bargains. Skilled labour is in short supply, particularly in the mining states, and the industry has been conducting a long-running argument with the Department of Immigration and Citizenship over the definition of "agricultural technicians" for 457 visa purposes.

Nevertheless, pig producers are not unaware of changing consumer sensitivities. The industry group Australian Pork has agreed to phase out sow gestation stalls by 2017.

Tasmania, thanks to a $500,000 adjustment grant from the state government, is due to be stall-free as soon as next month. Australian Pork has commissioned research into pig body language.

Its annual report displays signs of an industry that knows it must keep up with the times and is doing its best to do so.

On top of everything, however, the illegal vigilante behaviour of fanatics with video cameras is causing expense and disturbance to an industry that hardly needs or deserves it. Activists show scant regard for the rules of trespass or privacy and, ironically, scant regard for the welfare of the animals. Their intrusion causes distress and breaches biosecurity.

The risk of activist-borne contamination is not taken lightly. In the pathogen-free sector, which operates under the strictest of guidelines, it could lead to the slaughter of the entire stock.

Ignorance, however, is on the activists' side; the knowledge gap between city and country has never been wider, and fewer Australians have any experience of the gritty reality of farming. The sawdust, chopper and block of the butchers shop is largely pushed behind the scenes, and meat arrives in hygienic cling-wrapped polystyrene packets in the supermarket chiller.

As the cat reminded the cute talking pig in the movie Babe: "Believe me, sooner or later, every pig gets eaten. That's the way the world works. Oh, I haven't upset you, have I?"