In February the Victorian branch of the Construction Forestry Mining and Energy Union threatened to abandon its support for Daniel Andrews’s state Labor government because the Police Minister said something nice about a construction company.

Union boss John Setka reached for his favourite adjective, calling the government “a f..king disgrace”, all because Lisa Neville had praised Grocon for its help in cleaning up Wye River after a bushfire.

In a less imperfect world with a less imperfect labour movement, Andrews might have told Setka to get nicked. But since the union contributed the best part of $500,000 to Andrews’s election fund he could hardly afford a principled stand.

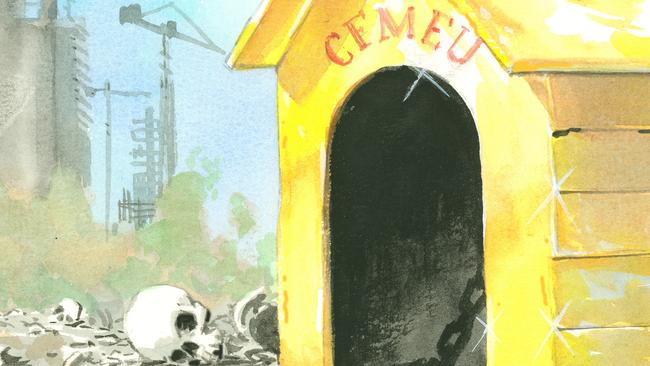

If the CFMEU were a dog, it would be an irascible, snarling breed, the kind only a tattooed misfit with a pierced nose and absurdly large biceps would dream of keeping as a pet. So long as it remains part of what Bill Shorten calls “the mighty trade union movement” the CFMEU will continue to embarrass the party with its thuggish behaviour.

Last week Setka made public threats against Australian Building and Construction Commission inspectors.

“We’re going to expose them all,” Setka told a CFMEU rally in Melbourne. “We will lobby their neighbourhoods. We will tell them who lives in that house. What he does for a living, or she. We will go to their local football club. We will go to the local shopping centre.

“They will not be able to show their faces anywhere. Their kids will be ashamed of who their parents are.”

If ABCC inspectors were an ethnic minority, Setka’s offensive, insulting, humiliating and intimidating speech would have provided ample ground for complaint under section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act.

But since they are people who are merely trying to do their job — ensuring that unions stay within the law — they have no such protection. It was mere “hyperbole”, the union claimed in defence of Setka, who apparently had been taken out of context. The Opposition Leader’s office went through its familiar routine: furrowed brows, earnest platitudes, repudiation in the strongest possible terms, et cetera. Yet Shorten can’t be taken seriously on this topic, not while his party continues to take the CFMEU’s shilling and the party remains committed to abolishing the ABCC in government.

Despite the Coalition’s best endeavours, the reconstitution of the ABCC has done little to reassure the public that the CFMEU is accountable to law. At best it has succeeded in merely loosening the CFMEU’s grip on the construction industry, where fear of intimidation, boycotts and bloody-minded industrial action keeps developers awake at night.

The union is a political force in its own right. It probably has more cash in the bank than the Liberal Party. Growth in the construction sector has increased its pool of potential members, while its business model has evolved to draw revenue by devious means from their employers.

Andrews kept his own counsel last week, presumably because he will rely heavily on CFMEU support to put grunt into next year’s election campaign, just as he did in 2014 and Shorten did last year.

The presence of union heavies at pre-polling stations in marginal seats was just one of many supportive gestures by Labor’s many friends.

It has a radical chic following among Labor’s intelligentsia for whom the pit bulls in fluoro vests are cast in a romantic vein as protectors of the weak against the strong. Guardian Australia columnist Van Badham, who boasted of joining the march last week, has described the CFMEU as “cuddly”.

There is little room in this contrived progressive narrative to consider the long-term consequences of the union’s dominance on the broader economy, or indeed jobs in the construction sector, which employs more workers than manufacturing.

Excessive enterprise bargaining agreements — pattern bargaining in all but name — are killing the jobs the CFMEU claims to protect.

As in the 19th century when the wool industry was held hostage by bolshie shearers, the high cost of labour provides a strong incentive to innovation. The breakthrough for wool came in the late 1880s when Frederick Wolseley’s mechanical shears revolutionised the woolsheds.

The machine, The Argus reported, would sound “the death knell … of an old colonial order … quicker than a hundred-a-day shearer … and any man may learn to work it in a week. Chinamen and roustabouts and blackfellows will all be shearers now.”

It is surely no coincidence that a West Australian company is leading the world in developing a robotic bricklaying machine, the construction sector’s equivalent of the mechanical shears.

The Hadrian X, named after the Roman emperor, will be on the market in two years, capable of laying 1000 bricks an hour, twice as many as the average human bricklayer can manage in a day.

It will operate around the clock in blatant defiance of the union EBA: no tea breaks, no strike meetings, no rostered days off and no protest marches through the Melbourne CBD at inconvenient times of the day.

The digital revolution is disrupting the construction industry as radically as any other. Steel fabrication is now a trade-exposed industry; work is progressively moving offshore, driven by steep energy costs and high wages. Giant conglomerates in Asia can supply large volumes of structural steel at a much lower cost, even incorporating the cost of transport.

If the Sydney Harbour Bridge were built today there would be no need for the fabrication yards built on what later became Luna Park. Today, foreign-made steel would be fabricated offshore and shipped in like the parts of a Meccano set.

In another flashback to less enlightened times, governments state and federal have responded with a return to protection, mandating local steel for government jobs. It is a backward step that will entrench inefficient working practices, low productivity and high wages.

As the final Australian-built Holdens roll off the production line at South Australia’s Elizabeth plant, the lessons for the construction sector are clear. Anti-competitive practices of the kind championed by the CFMEU will hasten Australia’s passage on the fast road to decline.

Nick Cater is executive director of the Menzies Research Centre.