Cast your mind back to 1989 and the golden age of political incorrectness when a prime minister could call a pensioner a silly old bugger without being lectured by finger-waggers.

Bob Hawke’s encounter with a curmudgeonly 74-year-old hardly dented his election campaign. It was a sign that Hawke was human, a quality voters seem to like in a prime minister, funnily enough.

Today it would be declared a blunder and subjected to forensic analysis by po-faced writers for Guardian Australia, who would agree with the ABC’s Fran Kelly, as they usually do, that it was a gaffe from which Hawke might never recover.

Now Hawke himself is an old white male, as we are still allowed to call them, apparently. He and John Howard found themselves in surprising agreement in an absorbing discussion, punctuated by the ABC’s chirpy Annabel Crabb, at a Canberra dinner last week.

Disregarding Hawke’s apocalyptic climate change imaginings and his obsession with abolishing the states, the two prime ministers operated as a tag team, lamenting the failure of leadership and the failings of the fourth estate with the wisdom that experience endows.

Unusually, perhaps, it was broadcast live by the ABC, a broadcaster that would not normally trust a couple of old codgers with an open microphone. The corporation, together with much of the media, seems to believe that anyone over 50 is past it, “run down, old-fashioned, puzzled and resentful”, as Donald Horne described his elders in his mid-century manifesto for modernity, The Lucky Country.

The restiveness of youth, captured by Horne, held that members of the Menzies-Calwell generation were “exiles in their own century”. The same impatience is apparent today with the rise of an assertive, self-regarding cohort convinced it sees the world in clearer terms than its predecessors.

They are separated by a generational cultural divide that has seldom seemed wider. Like the hip young things of the 1960s and 70s, they exhibit mores that signal their rejection of the things they call old school.

Youthful baby boomers distinguished themselves as a generation apart through music, clothes and sexual liberation. For the hipsters it is food, clothes and a tyrannical devotion to political correctness. Horne could be writing about the millennials when he describes the “New Generation”. “It is still condemned as hedonistic and stupid,” writes Horne, “yet … it may be the generation that changes Australia.”

Today’s political establishment faces a challenge no less greater than that which threw the major parties in confusion a half century ago as they struggled to stay “with it”. Labor’s Arthur Calwell, described by Horne as “some relic of early man”, was deposed by Gough Whitlam who, at 51, reinvented himself as the voice of youth. Bob Menzies had retired a year earlier, leaving a procession of leaders to wrestle with the “modernisation” of the Liberal Party — whatever that might involve — creating a philosophical quandary that took almost 30 years to resolve.

Today’s political leaders could draw lessons from that period, if they took the trouble to do so. The first was the mistake of thinking conservative views would give way to the age of Aquarius, and that the progressive attitudes of the educated youth rapidly would occupy the minds of everyone.

Whitlam’s ascendancy alienated the conservative blue-collar vote, while attempted shifts of emphasis in the Liberal Party introduce similar tensions in its base. Yet standing still is never an option for political parties, which face the eternal challenge of applying defining principles to the policy challenges of the day in language that resonates with the times.

Seldom, if ever, has age been such an important determinant of political attitudes in Western democracies. Millennials — who for convenience we will think of a voters aged 18 to 34 — behave very differently from the older generations in ways that political science has yet to explain. They are motivated by causes rather than a broad platform of public policy; they are less likely to vote the same way as their parents; identity politics tends to override party politics.

In crude political terms, however, they are leaning further to the left. Had the millennials prevailed in Britain, for example, Jeremy Corbyn would have won by a landslide and the country’s place in Europe would have been assured with a comfortable vote to remain.

The same picture, albeit more ragged at the edges, is emerging in Australia.

Labor holds 42 of the 50 electorates with the highest proportion of millennial voters. The Liberals and the Liberal National Party hold seven while the Greens hold Melbourne, the most youthful seat in the country.

The Coalition, on the other hand, represents 35 of the 50 seats with the highest proportion of voters over 54. Two are held by independents, one by Nick Xenophon’s party and 12 by Labor.

Coalition strategists may care to ponder why they lost six of those seats at the election last year and whether it may be evidence of waning support among older voters, who were supposed to be rusted on.

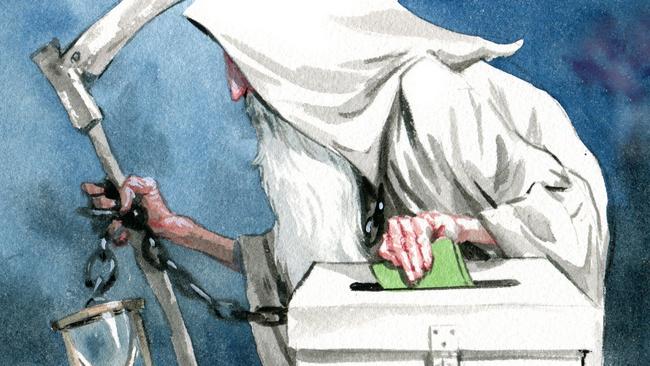

At first glance it may seem that the future belongs to Labor’s bright young things while the Coalition tries to rustle up support in God’s waiting room.

Yet medical science and an ageing population are doing curious things to electoral demographics. The average age of those eligible to vote in the 1975 election was a little over 42. Now the average voter is over 47 and rising.

Australians turning 60 in 1975 could expect to vote in five more elections. Today they can anticipate seven or eight.

In 1975, when Whitlam lost power, 40 per cent of eligible voters were under 35. The over-55s commanded just 25 per cent of the vote. Now the tables have been turned. For the first time, the over-55s were the largest cohort in last year’s election, commanding more than 35 per cent of the vote. The millennials’ share was a little more than 30 per cent.

This curious inversion in the age profile will ensure that the oldies have the numbers for a couple of decades at least. Beware the wrath of the silly old buggers.

Nick Cater is executive director of the Menzies Research Centre.