PORT Augusta may be online by Christmas, we are told, more than six years after Kevin Rudd promised us a high-speed broadband network that would take five years to build. Regretfully, there is no such good news for Lane Cove or Thebarton - like painting the skirting boards, nation building takes longer than you think.

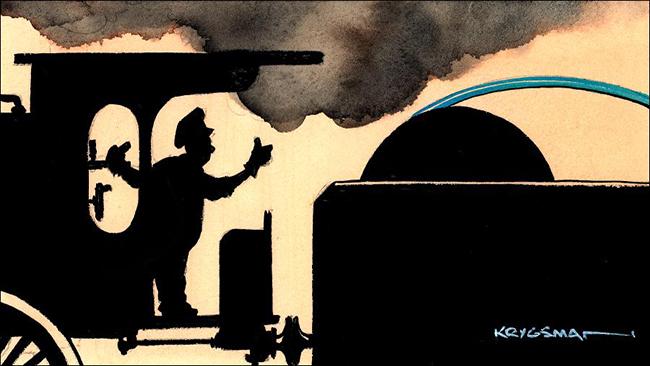

It seems Rudd was not joking when he compared the construction of a fibre-optic network to 19th-century railway building. Then, as now, a collective madness seemed to sweep a nation enthralled by new technology, the business case was flimsy, the private sector wouldn't touch it and the bill to the taxpayer was staggeringly large.

In 1862 The Gippsland Times urged readers to "look sternly in the face of futurity" and imagine what would become of the region if the railway passed it by: "We would have to go back to the primitive life ... where nothing was known nor required beyond what was yielded by the native soil or contributed by the animals which grazed on their mountain sides."

Sixteen years later, The Gipper got its way. The line to Bairnsdale was opened in 1888 and extended to Orbost in 1916, allowing the upper Gippsland forests to be stripped in a fraction of the time it would otherwise have taken.

Empty passenger trains lumbered on between Sale and Bairnsdale, bleeding the public purse, until Jeff Kennett put them out of their misery in 1993 and Victorians could once again look sternly in the face of futurity without staring at a wall of state debt.

A fascination with trains, however, is apt to turn grown men to treacle. In 2003, Steve Bracks put on that hard hat worn by premiers when announcing bone-headed projects and drove the first spikes into new railway sleepers at Bairnsdale to launch a $12 million restoration project. The Age, a paper with a railway fetish, signed up to the plan straight off the press release, agreeing with Bracks that it was "the biggest upgrade of the rail line in 120 years".

The reopened track has been a godsend for those who never catch a train but imagine that one day they may. Who needs that peak hour traffic when you can hop on a train at Bairnsdale at 6.20, change at Sale, again at Traralgon and be at Southern Cross station by 10? What better way to spend a morning than watching the countryside zip past at a dizzying 70km/h?

In Europe, steam locomotion drove the industrial revolution and in the US the railroads opened the mid-west and joined a continent. In Australia each state government fought to keep the traffic flowing through its ports, and railways fanned out from state capitals like spiders' webs, barely touching at the edges.

In the US, speculators risked their own money on railways and built them light, keeping the engineers in their place. In Australia, state governments brought in British engineers who mostly insisted on pukka broad gauge tracks, vastly increasing the cost.

Railway building went crazy in the 1880s on the back of a resources boom, sucking scarce capital and labour from the private sector, pushing up wages and inflation. This, and rising state government debt, contributed in no small part to the slump of the 1890s and it did not stop there.

The debt went on accumulating, driving NSW to the brink of bankruptcy in the early 1930s.

Steam locomotion technology was almost 100 years old by the time of the Australian railway boom, yet no one foresaw that it would face competition from a nimbler, cheaper form of transport. Karl Benz patented his internal combustion engine seven years before Bairnsdale got its railway, and commercial oil production had been going on for 30 years in the Caspian Sea.

Yet government spending on railways exceeded road spending well into the 20th century. It was not until World War I that bureaucrats figured out the horseless carriage was here to stay.

With such in-built resistance to new technology, it's not surprising Stephen Conroy sometimes looks a little bonkers on ABC1's Lateline, as he explains for the umpteenth time how the National Broadband Network is going to change our lives. Emma Alberici just doesn't get it. Few Australians do, in the sense of having an actual fibre attached to the house.

We are grateful, therefore, to Josh of Point Cook, Victoria, for giving us a glimpse of life in the fast lane of the information superhighway. He tells ITnews: "I no longer venture down to the video store to hire a video." Why would he, when he has TiVo and can download an entire movie in 14 to 15 minutes? That may be a little bit slower than many of us anticipated, but Josh tells us the kids can now play World of Warcraft with "no lag, no disconnections, (and) no staggered picture". You've got to be happy with that.

Well, we would be, were it not for the Iron Law of Gadgets, which dictates that within seconds of swiping your credit card, Sony comes out with a new one.

The Japanese are getting a fibre-based internet service that delivers 2 gigabits per second, 20 times faster than Conroy's NBN.

We are indebted to Arthur Lowery, professor of electrical and computer systems at Monash University, for explaining what a difference 2Gbps could make to daily life. "A 2Gbps connection means you could download an episode of HBO's hugely popular drama Game of Thrones in seconds," he writes on the university-sector subsidised website The Conversation. "And given the first episode of the current season was illegally downloaded more than a million times, that would presumably be a welcome development."

Not for David Benioff and DB Weiss, Game of Thrones' creators, who were hoping to turn a buck. Epic medieval fantasy dramas don't just write themselves. But as the professor suggests, 2Gb is fast becoming a necessity. Imagine the situation, he suggests: "I need to download 10 movies before I fly out on holiday. The taxi just pulled up and the meter is running." Indeed, professor, we see your point. Heaven forbid you should find yourself on a journey without 10 movies to choose from, or 20, if you're intending to catch the train to Bairnsdale.