LIKE many of Gough Whitlam’s proclaimed accomplishments, the transformation of Australia into a nation of functionaries was not, strictly speaking, all his own work.

The expansion of the state since World War II has been a bipartisan project. Politicians on both sides of the chamber are prone to the delusion that government knows best.

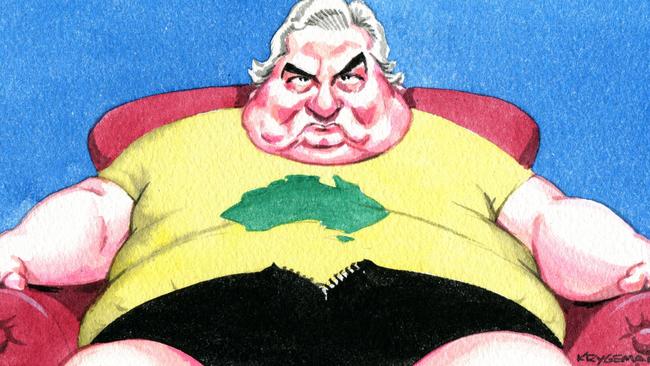

Few would disagree, however, that when it came to the bureaucratisation of Australia, Whitlam stood head, shoulders and torso above anyone else. When Robert Menzies spoke in 1942 of a future in which government “will nurse us and rear us and maintain us and pension us and bury us”, he was trying to scare us. When Whitlam spoke in similar terms he meant it as a promise.

“The quality of life depends less on the things which individuals obtain for themselves and can purchase for themselves from their personal incomes and depends more on the things which the community provides,” Whitlam said in 1975. Let’s not be fooled by that homely word “community”. We know exactly what Whitlam meant. The deep pockets of government would provide the cash and Whitlam, central planner par excellence, would write the program.

We now know better, of course, or should. As government expands, the productive economy shrinks, and before you know it we’re on the road to South Australia or, eventually, Greece.

Most of the current government’s greatest challenges have their origins in Whitlamism. Fiscal restraint, the reform of the federation and restoring dignity to demoralised welfare recipients are repudiations of Whitlamesque policies. Whitlam is not entirely to blame for the culture of entitlement, the promotion of rights decoupled from responsibilities, activist public broadcasting and the deadening utilitarian approach to higher education but, more than any other leader, he made a virtue of these vices.

The 1970s were golden years for the urban bourgeoisie and for that we must largely thank Whitlam. Public servants, teachers, doctors, social workers, artists, academics and our friends at the ABC were blessed with expanding opportunities and fatter pay packets while the economy tanked and private-sector workers lost jobs.

As Whitlam’s private secretary, Peter Wilenski, noted afterwards: “The first beneficiaries of any new program are the persons hired to administer it and ... these are predominantly the already privileged.” Peter Walsh, a future Labor finance minister, agreed: “The greatest beneficiaries of the reforms ... were those who gained sinecures in an expanded public sector and the white-collar middle class in particular.” Whitlam’s program, he concluded, “delivered few positives to the working-class constituency and big negatives in the form of high inflation and rising unemployment”.

In the 1971-72 budget $285 million was set aside for “general administration”, an activity we used to call pen-pushing in the age before computers. In 1975-76 the cost of general administration had risen to $668m, more than half as much again after accounting for inflation. For the public service they were glory days indeed.

Indeed they were glory days for Canberra, a country town that became a city of sorts in the 60s and 70s. Menzies’ contribution to the capital was to dam the Molonglo to create a lake; Whitlam’s was the bureaucratic sludge that oozed into every corner of our lives, muddying everything it touched.

It was the start of technocratic transformation that installed a permanent ruling class of experts, people Donald Horne looked towards for salvation when he wrote The Lucky Country in 1964. They were the group that “understands the demands of the age better and sees life in more complicated terms” than the average person.

The times demanded “a greater emphasis on administrative and managerial capacity and an absorption of the technocratic ways of thinking”, Horne wrote, and boy did Whitlam deliver. In the 1971 census, barely a quarter of Canberra’s working population worked in professional or administrative jobs. In 1981 it was more than half.

Whitlam’s faith in central planning and the potency of government was extraordinary.

In his election speech in 1972, he said a Labor government would restore and maintain growth by establishing “the machinery for continuing consultation and economic planning”.

“This is the real answer to the parrot-cry ‘Where’s the money coming from?’ ” he declared.

His program would be funded by “the automatic and inevitable massive growth in commonwealth revenues”.

For Whitlam, the federal government’s problem would not be raising cash but working out how to spend it. The Constitution restricted the federal government’s ability to spend directly on health and education since these were matters for the states. Looking back on his period in government in 1985, Whitlam explained that the constitutional limits on the national government, combined with a High Court intent on upholding them, had been “doubly demoralising” for an activist movement such as the ALP.

“In terms of the sheer survival of the ALP as a meaningful force, the task of developing a practical program for reform within the existing Constitution became a matter of great urgency,” he wrote.

In opposition, Whitlam dreamt of sweeping changes to the Constitution, pulling back the powers of the states and bolstering imperial powers in Canberra. When the reality of constitutional reform eventually struck him, he exploited foreign powers provisions and other constitutional loopholes to get the job done.

The centralisation of executive power in Canberra is another bipartisan project for which Whitlam cannot take all the credit. Yet his zeal was unmatched by any prime minister before or since.

When Whitlam’s death was announced last week, Tony Abbott delivered a warm, perhaps even affectionate, tribute. The fraternal regard of politicians one to another, fellow professionals who know how peculiarly difficult the game can be, was clearly on display. Beyond that, the Prime Minister respectfully avoided addressing Whitlamism or its continuing impact on the country.

On Saturday, Abbott delivered a major speech on reforming the federation, which in substance and style was in stark contrast to the Whitlamist approach. He signalled an end to the erosion of state powers, promising to make each level of government “sovereign in its own sphere”. He declared himself a pragmatic nationalist and a seeker of consensus. Any reform would be subject to negotiation and compromise, requiring the same give and take that allowed Australia’s separate colonies to unite more than a century ago.

Abbott signalled that on this, as on fiscal reform, he is the polar opposite to his crash-through-or-crash predecessor. Whitlam believed he could fix the world; Abbott aims merely improve it.

Nick Cater is executive director of the Menzies Research Centre.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout