I’m glad Foreign Minister Julie Bishop has declared that satire plays an important role in Australian society. I presume she was referring to the grandly titled National Innovation and Science Agenda.

My absolute favourite part of the innovation statement released yesterday is government as exemplar. Is this some kind of joke? Have you been down to a Centrelink office recently? And did you notice that the ride-sharing service Uber was declared illegal in Victoria last week?

But don’t forget the possibilities of Big Data, information that you have been compelled to provide to government agencies, being sold to inner-city hipsters to develop some kind of app to enable enfeebled individuals to be told when to leave a meeting or something equally vacuous. Evidently, the future is data curating, access protocols and wider release — just in case you were wondering.

And don’t you just love the new-found enthusiasm for STEM. (If you don’t know what that stands for, you’re just not with the program.) The reality is that science, technology, engineering and mathematics have been downgraded in the school curriculum across many years. Students are allowed to opt out of maths and science at a very early stage. And there has been a catastrophic decline in the number of students undertaking advanced maths at Year 12.

Mind you, this is hardly surprising given the calibre and qualifications of the teaching workforce. Many bright students opt to study mushy and pointless subjects such as legal studies, physical education, tourism and community studies.

But surely a few hours of instruction in computer coding in primary school will make a great deal of difference? It could be like the results from teaching a smattering of foreign languages to primary school students.

Is there anything of value in the innovation statement? One billion dollars sounds like a lot of money given our chasm-sized budget deficit, but my hope is that there is a lot of rebadging and reshuffling going on.

This is one of every government’s favourite tactics: rename a program, then announce it on multiple occasions. This is sufficiently confusing to some punters to lead them to believe the government is actually achieving something rather than just wasting taxpayers’ money.

Another part of the government’s strategy is to repeat a series of contentious assertions to the point that even the politicians believe them. We are good at research but hopeless at commercialisation is the most popular.

Take this little homily from deeply inexperienced but much-travelled Assistant Innovation Minister Wyatt Roy. “That’s where we’ve got to see the role of government is bringing together both sides — the private sector, the incredible research we do, so we commercialise things and create these incredible businesses, products, ideas that change the world for the better.” Oh please.

But are we really good at research given the billions of dollars invested? And is commercialisation really the Holy Grail?

Indeed, in its more sensible days, the Productivity Commission made the important point that “the pursuit of commercialisation for financial gain by universities, while important in its own right, should not be to the detriment of maximising the broader returns from the productive use of university research”.

And if we can quickly adopt new innovations developed elsewhere, it means we haven’t borne the cost and risk of developing them. It is also completely wrong to think about innovation as equal to start-ups. The most important source comes from existing enterprises in the form of process innovation, not product innovation.

At least the innovation statement will make tax accountants and lawyers very happy folk in this festive season. A 20 per cent tax offset and a capital-gains tax exemption after three years of investment in a start-up (definition malleable) — now that’s a good start for a new line in fruitful tax planning.

This policy is like the old managed investment schemes in agriculture. Investors were driven by the tax advantages and most of the schemes went belly-up: think dying trees on leased land. But obviously someone in government thinks these tax-driven schemes were such a success that we should repeat the experiment because this time we will get the details right. The next sentence must surely include the words: head, banging and brick wall.

These same accountants and lawyers will also be licking their lips at the prospect of changes to the bankruptcy laws. Who cares about creditors who stump up cash and provide services to a failing firm when the debts can be written off and the directors of the firm can proceed as if nothing had happened? The important point is that the firm doesn’t fail, even if the previous suppliers and financiers to the firm go broke.

The reality is that there have been multiple government innovation statements through the years, from federal and state governments. Indeed, some of the agreed positions emanating from Kevin Rudd’s 2020 Summit (yes, I did attend but I was young and naive then) are remarkably similar to yesterday’s offerings.

The much more sensible approach by the government would be to enact measures to make it easier for all businesses to operate. This involves getting government out of the way, removing the layers of regulations, making it easier and more affordable to hire and fire workers, and to lower the tax burden on all players.

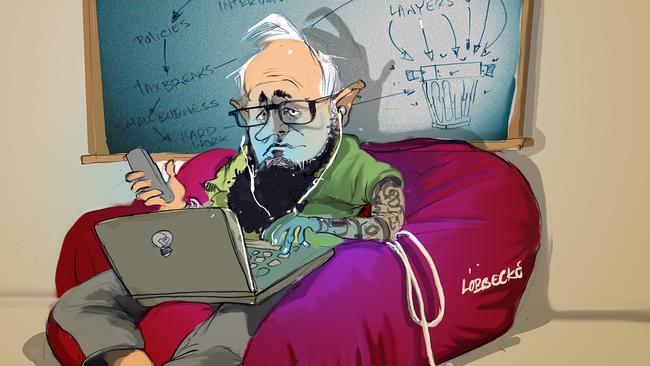

But I guess picking winners (but failures will be OK too because we are being instructed not to fear failure) is so much more attractive to politicians, particularly if it can be wrapped up in an endless stream of buzz words such as high-growth entrepreneurial ecosystem, innovation hubs, technology accelerators, culture of ideas, capability maps, and on and on.

But let me end on a positive note. There may be a serious spin-off from this innovation statement, by providing more than enough material for a second series of the ABC television program Utopia, a satirical take on lofty-sounding government policies that founder on the rocks of unattainable objects, poor design and incompetent managers. But as long as the vibe is right, the politicians don’t seem to mind.