In this newspaper’s annual stocktake of the views of business chief executives, the issue of energy prices frequently was mentioned as being of serious concern.

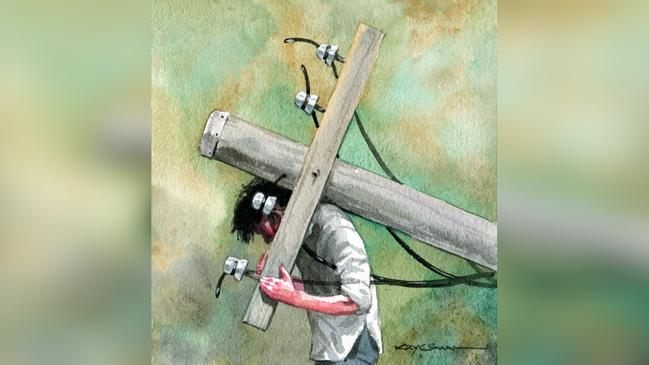

Energy-intensive businesses are finding their input costs escalating as the prices of wholesale electricity and gas rise at a much faster rate than consumer prices. But all businesses are affected by rising energy prices.

We also know from the recently released annual report on the performance of the retail energy market by the Australian Energy Regulator that “more … households are experiencing difficulty paying their power bills”.

One shocking revelation was that low-income households in South Australia on standard offers are spending more than 11 per cent of their disposable incomes on electricity. The highest rate of electricity price rises in 2017-18 was 22 per cent in South Australia for those on standard offers and close to 23 per cent in the ACT for those on market offers.

Unsurprisingly, there has been a sharp jump in the number of disconnections as well as the number of customers entering into hardship programs.

But how do electricity prices in Australia compare with overseas?

In a study by Alex Robson, released last week by the University of Sydney’s United States Studies Centre, comparisons are presented between energy costs in Australia and the US.

The bottom line is that Australian households and businesses routinely pay two to three times as much as their US counterparts. Energy in the US also is more reliable and the pricing arrangements are more transparent.

In the past decade, average power prices in Australia increased in real terms by about 70 per cent for households and businesses. In the US, real electricity prices for households stayed essentially flat; those for industrial users dropped by 10 per cent. When it comes to gas, the picture also is alarming. Australian manufacturers are being charged almost 50 per cent more in real terms than they were a decade ago, whereas manufacturers in the US are paying nearly two-thirds less. The average real price of gas also has fallen significantly for US households.

As Robson sums up: “On electricity and gas price outcomes, the two economies have taken completely opposite paths.”

It is hardly surprising that Scott Morrison would task Energy Minister Angus Taylor with getting electricity prices down. Of course, it’s easier said than done.

To foster lower prices, there must be robust and reliable analysis of why our energy prices are so high, both relative to the past and compared with overseas. Much of the blame can be sheeted home to highly defective policy settings imposed by states and territories, such as banning the exploitation of unconventional gas and setting renewable energy targets without requiring firmed back-up.

But when it comes to fixing the mess, there is an expectation that the federal government will be the frontrunner.

Don’t get me wrong: the renewable energy target — large-scale and small-scale — is one of the worst examples of public policy intervention that Australian households and businesses have endured. The faulty RET settings — actually, having an RET at all — have been the bedrock of faulty policy more generally. The key question is what Taylor can do in the short term that may lead to lower energy prices. There is a variety of ways of achieving better outcomes and it is necessary to work on all fronts.

An example of low-hanging fruit is the insistence that retailers offer better deals to customers on standing offers. The fact loyal customers have been dudded, including by the large energy companies that account for 70 per cent of the market, is outrageous and needs to be rectified quickly.

But contrary to the lobbyists for those big energy companies, some of whom are aligned with the Liberal Party and have been seeking to influence the voting behaviour of government backbenchers, the idea of forced divestment of assets to ensure more competitive markets is not an anti-Liberal idea.

Using the example of someone who is a hero of many economists, Republican US president Theodore Roosevelt, who broke up the large oil and transport monopolies, thereby setting up the US for decades of economic prosperity, the divestment option — or at least the threat — has much to commend itself. It’s not about the Liberal Party doing favours for big business, it’s about getting a better deal for customers.

Even casual observation of the component parts of the electricity industry leads to the conclusion that there are widespread pockets of market concentration. To be sure, instances of misconduct have to be investigated thoroughly and any legal orders requiring divestment must go through a court procedure.

Ordinarily, Labor would be highly focused on the potential dangers of market concentration. After all, assistant Treasury spokesman Andrew Leigh has been banging on about this for years. But when it comes to the big energy companies, Labor sings a different tune. In what seems a glaring example of crony capitalism, the view appears to be that if those big energy companies are at loggerheads with the government, they must be Labor’s friends.

Returning to why energy prices are high, it is clear that the explosion of investment in renewable energy, spurred by the RET and state and territory government policies, has not led to the promised nirvana of lower prices. (My advice is to take all those claims of renewable energy being cheaper than fossil fuels with a grain — nay, a tonne — of salt.)

The key missing ingredient has been investment in firming capacity that is available when renewable energy sources don’t generate any power, which is about 30 per cent to 50 per cent of the time. Taylor is focused on ensuring that this hole in the market is filled, and not by the big energy companies. This is in addition to more reliable baseload power, which also will be required in the near future.

The government has established a competitive tender arrangement, seeking investment proposals to fill these glaring gaps in the market. Note also that the mandate of the Clean Energy Finance Corporation will be extended to cover new firming projects that are required to complement the greater prevalence of renewable energy.

For the first time in many years, progress is being made that may lead to lower prices. Some of the initiatives could come to nothing — there is little time — and the states and territories continue to act in perverse ways that put upward pressure on prices. But recognising the challenges is always the best way to start the journey.

In case you are still wondering how we managed to get into this invidious pickle — from having close to the cheapest energy in the world to among the most expensive — consider this observation by Robson. During the past decade, carbon dioxide emissions from electricity generation in the US have declined at more than twice the rate of Australia’s emissions.

In other words, we have borne the pain of rapidly rising energy prices and have achieved much less than our US cousins in terms of emissions reductions. It is a clear case of wrong way, go back.