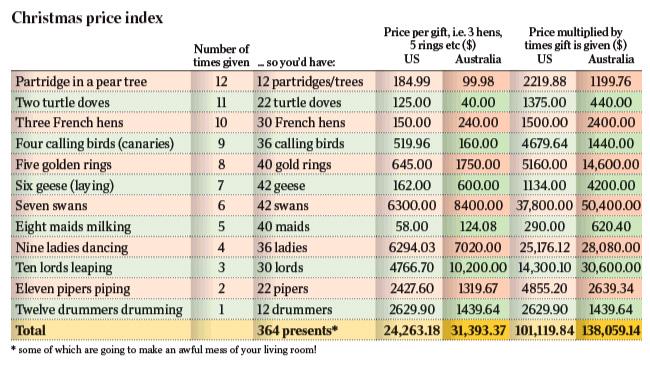

THE good news is that the Twelve Days of Christmas are cheaper than they were last year. Prices, as measured by the Twelve Days of Christmas (12C) price index (for a full explanation see my column of December 23 last year), have barely gone up in Australia despite the consumer price index rising by 3.5 per cent. So in real terms partridges and pear trees are better value, though to buy all 364 presents will still set your true love back $138,059 and 14c.

The bad news, however, is that the Twelve Days of Christmas package - from the first partridge to the last drummer drumming - still costs 37 per cent more in Australia than in the US. But so do Big Macs ($4.94 compared with $4.07), movie tickets ($14.01 compared with $7.40) and, yes, even chainsaws ($1100 compared with $650 - little wonder they get all the best massacres).

The 12C price index is therefore consistent with the Peterson Institute for International Economics' estimate that the Australian dollar should be trading at about US85c, rather than above parity.

Whether the gravitational force of yuletide economics will outweigh the prayers of millions of Australians for the $A to remain in the stratosphere is obviously a big question for next year.

But while the little Aussie battler is doing well, not everyone is swimming in milk and honey. Our supplier of rare birds has had a miserable year, with floods and fire devastating his property. Even so, swans cost no more than 12 months ago: indeed, some unscrupulous traders are discounting, spoiling the market for this quality product. Could this be a leading indicator for the fate of our Top Swan in Canberra? At least US swan prices are rising: maybe they need the world's greatest Treasurer more than we do.

As for the performers, the 12C index shows that with a little help from Fair Work Australia, unionised groups - maids milking and pipers piping - have managed to increase their prices (along with producers of rings, though that reflects the rising price of gold).

No wage joy, however, for the non-unionised ladies dancing and lords leaping, where competition kept earnings constant. Then again, why should minor aristocrats get anything from a Labor government?

That unions should flourish while others struggle would come as no surprise to the authors of our carol. After all, medieval trade was dominated by guilds, which limited entry, harassed competitors and fixed prices.

When the late 14th-century merchant William Lovesdale sold his fowls in Yaxley at less than the mandated price, the local guild "laid in wait and wounded, beat and evilly treated him, and left him there in despair of his life"'

Sure, the guild argued it was merely protecting fair trade; but guild practices, a crown attorney said, "redound to the injury, oppression and pauperisation of the people". And a jury of 12 flatly rejected the public interest claims, finding "the profit does not accrue to the advantage of the community but only of those who are of the said society".

Yet the guilds prospered. For as Sheilagh Ogilvie, professor of economic history at Cambridge, recently put it, "an institution that keeps the economic pie small but distributes large slices to powerful groups can be sustained for centuries by its beneficiaries. Merchant guilds were not an efficient institution that increased aggregate wealth. But they enabled workers and rulers to collaborate effectively in extracting larger shares of it for themselves."

Plus ca change, one might think. But by the time The Twelve Days of Christmas was written, change was in the air. Particularly in England and The Netherlands, guilds lost their stranglehold over local trade, not least because rulers found better ways of raising taxes, including by taxing a wider base of commerce. And that greater commerce was encouraged by the repeal, in 1604, of England's sumptuary laws, which prohibited commoners from buying luxuries and frivolities.

Trade was still very small scale, but new goods, embodying an element of fashion, quickly became widespread. Porcelain, for example: first imported commercially from China in 1630, by the end of the 18th century more than 40 million pieces had made the journey from a single industrial complex in the Chinese city of Jingdezhen.

Clothing too, formed a crucial part of what Sir James Steuart, in an early text on political economy, termed "the desires that proceed from the affections of the mind".

With small purchases, costing less than an extra 1s 8d a week (well below the weekly earnings of an outworker), women could buy that emblem of respectability, clean white linen, and experience a new sense of change. And soon pocket watches would become a coveted possession of every social class, with Adam Smith complaining that such "trinkets of frivolous utility" had proliferated to the point where "lovers of toys contrive new pockets in order to carry a greater number".

Not that monopoly privileges, and the distortions they cause, disappeared. The emergence of distant trading opportunities led to the chartering of new corporations, most famously the English East India Company, which in 1600 gained a monopoly over trade to the East, initially for 15 years but renewed until 1858.

It not only played a crucial role in developing the tea trade, but bribed governments into imposing stiff taxes on coffee, whose production was controlled by its Dutch and French rivals. So while English coffee consumption was less than a tenth that on the Continent, England absorbed 60 per cent of all tea shipped to Europe.

Nor was the East India Company the only successful lobbyist. A white bread revolution was under way, displacing coarser, less readily digested but more durable alternatives. So dramatic was wheat flour's ascendancy that parliament, to protect the rye industry, enacted that gem of misnamed legislation, the Stale Bread Act, prohibiting the sale of freshly baked bread.

Very low grain prices also bolstered demand for distilled drinks, while consumption of beer and wine fell. In 1736, restrictive legislation was introduced to curb the sale of gin, but gin was soon replaced by brandies and rum, taking annual consumption to more six litres a man, woman and child. And that was still well below American levels, which, at the eve of the revolution, stood, for rum alone, at 16 litres per capita.

All this awaited the original carollers, who would soon discover that, under capitalism, many of the best things in life, even if not free, are surprisingly cheap. Then again, for all their wowsers and rent-seekers, they didn't have carbon taxes to worry about.

But perhaps we don't need to worry that much. After all, Treasury spent the year assuring us a seamless world market for carbon permits would emerge by 2016. And those permits have been trading in Europe for barely a ha'penny. Why, were it not for the floor price, European carbon permits would be cheap enough to feed to the swan. Now that's something to wish for.