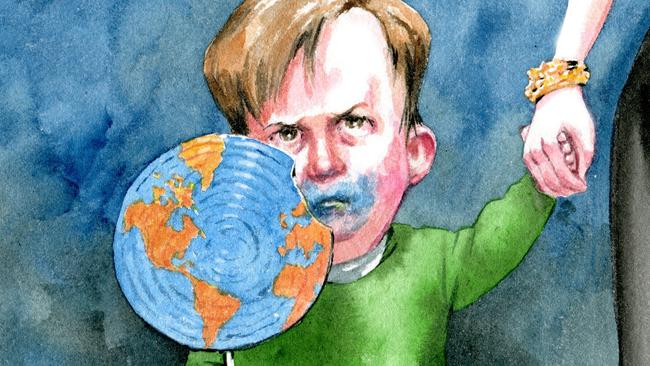

The phrase “First World problem” started as a funny meme, became a common hashtag on social media and soon enough entered dictionaries. Surveys about First World problems find that slow internet speed tops the list, along with not finding your favourite food on your local supermarket shelf. We tell this lame joke at the expense of our own wealth, except that our good fortune has also created another set of First World problems. And they are deadly serious.

Some are literally deadly. Last weekend, Seth Berkley, the chief executive of Gavi, an alliance between the World Health Organisation and drug makers to distribute vaccines to poor countries, said he was increasingly worried by the outbreak of preventable diseases in the developed world.

Berkley pointed to the rich phenomenon of “Whole Foods mums” who feed their children organic produce and question whether vaccines are needed any more.

Here is a First World problem writ large: a lucky generation that has never known the misery, maiming and death caused by diseases that are now preventable thanks to modern-day vaccines. We haven’t seen young limbs mangled, children unable to breathe, drowning in their own secretions, when polio hit a peak of 39.1 per 100,000 people in 1938, with further outbreaks in 1956 and 1961. Today, polio is a thing of the past because a vaccine introduced in 1966 protects us from this killer disease.

We don’t see young children racked with spasms and cramp from tetanus, or suffocating from whooping cough. It’s likely we don’t know that 4075 people died from diphtheria between 1926 and 1935 and that deaths from the deadly disease fell to zero by 1990. Or that 2808 people, mainly small children, died from whooping cough between 1926 and 1935, with only a tiny fraction of deaths after 1986.

In Australia today, the more affluent the postcode, the more potent the complacency. The latest figures released in June show that in central Sydney, just 70.5 per cent of five-year-olds are fully vaccinated (worse than Byron Bay), compared with 99.5 per cent in Woonona, a northern suburb of Wollongong. My own suburb has an immunisation rate of 84.2 per cent, well below the 95 per cent cover that provides what doctors call herd immunity. South Australia has immunisation coverage at 93.4 per cent, exceeding the national average, yet in Adelaide just 91.9 per cent of five-year-olds are fully immunised. Perth has an immunisation rate of 90 per cent, compared with 99.2 per cent in Broome. Across the rich developed word, the “Whole Foods mum” phenomenon is putting lives at risk, while countries such as Zambia and Vietnam report higher rates of immunisation against measles, mumps and rubella than Britain.

Trying to confront this rich curse of complacency, the Turnbull government last week beefed up the “no jab, no pay” laws. Parents on Family Tax Benefit A will have their fortnightly payments reduced by $28 if their children are not immunised.

It’s hoped that the more immediate cut to benefits, instead of previous cuts to end-of-year supplements, will inspire more parents to fully immunise their children sooner rather than later.

When former prime minister Tony Abbott first introduced the “no jab, no pay” policy a few years ago, ABC’s AM radio program ran an interview with academic Raina MacIntyre, who criticised the move to dock welfare payments to parents: “They work, they pay taxes. They have an entitlement to those benefits.” Succumbing to this First World problem, the head of the school of public health and community medicine at the University of NSW inadvertently pointed to another one too.

Too many of us are members of the entitlement generation because we have never experienced the horror of a depression or even a recession. After 26 straight years without a recession, economic vanity has reached the point where every move to cut benefits — even when parents don’t vaccinate their kids — is met with howls of outrage. It’s afflicted our political leaders, too. Instead of serious attempts to reform structural entitlement spending baked into the budget, the Turnbull government chose the easy path of a bank levy to plug the fiscal hole. Will it take real hardship, a recession perhaps, for common sense to trump this complacency?

We are a lucky generation indeed, one that has no experience of communism or socialism either. Casting aside the Cold War as old history, many in the rich First World continue their love affair with socialism, even as food shortages in socialist Venezuela kill people daily. Inflation there is set to reach 720 per cent and supermarket shelves are emptying. When you can find food, a basket of basics costs four times the monthly minimum wage, according to the Venezuela-based Centre for Social Analysis and Documentation. It might be fun for the Greens and Labor leader Bill Shorten to flirt with socialism, promising to spend more of other people’s money and to tax the rich more. Until we end up living the consequences of that conceit too.

Other First World problems are equally perilous. We are the generation that has no experience of living without basic freedoms. So we take them for granted and regularly curb them without understanding that we are chipping away at the core liberal project. The “cultural McCarthyism” that John Howard warned about in 1994 has taken hold. Freedom of speech is routinely curtailed in the name of not hurting someone’s feelings. Universities are cottonwool campuses that offer safe spaces and trigger warnings rather than robust intellectual learning.

Students regularly resort to violence to silence people with different views. If liberalism is the measuring stick, this is not progress.

We are the generation that assumed we would be better parents than our own, by helicoptering over our children. Lawnmower parents try to clear the way for their kids, then Hoover up after them when things go wrong. The generation that will follow us is at risk of losing resilience to deal with the vicissitudes of life, suggesting we are not half as clever as we think we are.

We are the generation that also lost sight of the real meaning of equality. The civil rights movement was premised on equal political and legal rights regardless of race, creed, gender and sexuality. In the 21st century identity politics has become the ultimate First World indulgence, weaponising difference with scant regard for the consequences of dividing people into noisy identity-based tribes demanding different treatment.

Our smugness has extended to assuming we can live in the luxury of green fashion without paying the price. That folly has been exposed by skyrocketing electricity bills that hurt the poor the most, frequent blackouts, an unstable energy grid, local investors choosing to do business in countries with cheaper energy and foreigners sucking up taxpayer-funded subsidies in our rent-seeking renewables industry. A decade ago we didn’t need to ask our governments to keep the lights on. Now we do. More fool us.

There is a common denominator here. We tend to assume the story of humanity is one of constant progress. But we should remember that after the Roman Empire collapsed, western Europe returned to the Dark Ages for 1000 years until the Renaissance. First World arrogance has led to the most diabolic First World problem of all: a deluded belief that we are immune from going backwards.

janeta@bigpond.net.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout