Arriving in Australia many decades ago, the first thing I learned was that real Australians never complain. In this country, outrageous fortune seemed to be wasting her time: the cruellest slings and arrows were met with a stoicism that made Seneca look like a whingeing Pom.

This was a hard lesson to absorb, especially coming from a culture that viewed lamentation as an art form, and in which “How are you?” was interpreted not as a routine salutation but as an open-ended invitation to report on the fluctuating, yet always troubling, condition of one’s inner organs.

Gradually, however, I understood that it could scarcely have been otherwise. The national imagination had been forged by the land’s pitiless harshness. From Barcroft Boake’s “wastes of the Never Never … where the dead men lie” to the madness of Patrick White’s Voss, who is “humbled” by the desert for believing himself invulnerable, the “haunting presence of death and desolation” the explorer Cecil Madigan felt in the outback had fashioned a character that was emotionally sparse and proudly laconic.

Moreover, despite the fact that if Australians risked dying of thirst, it was mainly because the pubs closed at six o’clock, that character (or at least its ideal) had somehow survived in a highly urbanised society, as had the sardonic, stripped-down humour that accompanied it.

Little did I realise those survivals were on their last legs. Just as the lamington succumbed to avocado toast, so “such is life” was supplanted by a chorus of complaint as raucous as an army of cane toads on the march. And with consternation replacing conversation as the dominant mode of social interchange, public life descended into a steam-bath of emotions as long on anger as it was short on clarity of purpose.

Seen in narrowly commercial terms, this was yet another of life’s missed opportunities. After all, if bemoaning one’s fate was to become the national pastime, a vast market could have been cultivated for lessons in Yiddish, with its 19 words that convey shades of disparagement, minutely graded from mild disapproval to outright revulsion. That was not to be. But the puzzle remained: why had the world-weary shrug of the shoulders given way to the incessant demand for sympathy?

No doubt, long-term forces were at work. More than a century ago, the great French sociologist Emile Durkheim argued that the deepening division of labour that marked the transition from traditional to modern society generated a process of “individuation”, reducing the degree to which society envelops the individual and elevating the self to the centre of social life. As that happened, individual emotions acquired new prominence and came to be accepted as legitimate matters of concern. However, neither Durkheim nor his leading disciples expected “emoting” to burst on to the public stage.

On the contrary, Norbert Elias, the German pioneer of the history of manners, thought the greater the freedom individuals were granted to develop their innermost feelings, the greater would be the social pressures to manage them carefully. When Miss Manners said “Whining … is banned from social events … Whining is properly directed only at one’s intimates”, she was channelling Elias’s prediction of the ever rising importance of “affect control”.

It is this affect control that seems to have crumbled. But it is not just any emotions its collapse has unleashed: rather, it is the sense of victimhood and the cry for compensation.

Sympathy used to be reserved for searing tragedies; now, passing misfortunes are expected to trigger outpourings of grief.

In its own way, that is hardly mysterious. As American social theorist Candace Clark put it, to demand sympathy is to stage a morality play in which one is the undisputed star, with a plot framed to invoke broadly accepted notions of justice and injustice, hardship and desert. In a world in which more and more of life is played out in the public gaze, there is no surer way to claim a place, however fleeting, in the ruthless competition for attention.

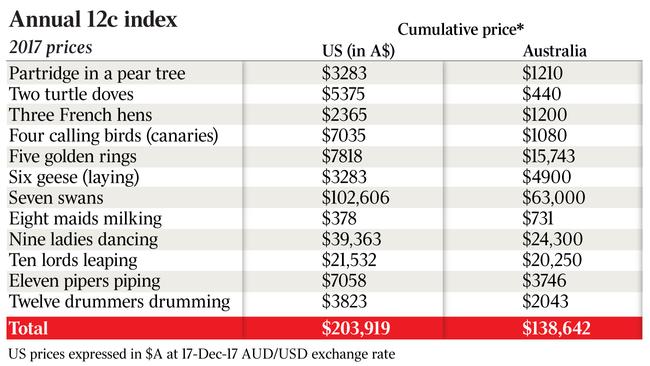

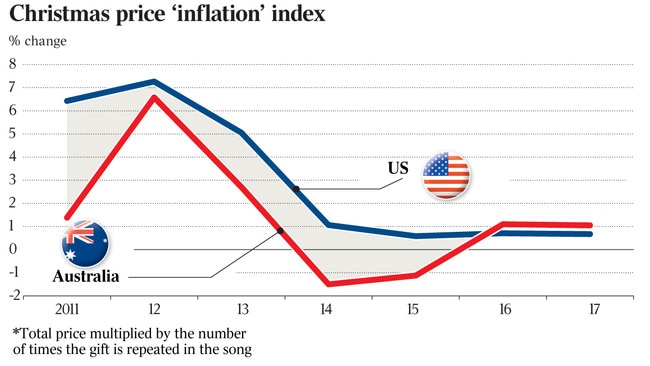

But that not only cheapens the quality of mercy; it also paints our lives as much grimmer than they are. Consider the Christmas Price Index, which every yuletide plots the cost in the US and Australia of purchasing the basket of goods and services specified in The Twelve Days of Christmas.

In the US, 90 per cent of the increase in its labour cost components since 2010 has come from gains by the ladies dancing and lords a-leaping; in Australia, on the other hand, the aristocrats’ real income has fallen by about 4 per cent a year, while “working people” — the maids a-milking, pipers piping and drummers drumming — have recorded average annual gains of 3 per cent, lifting their real income this decade by more than a third.

For sure, this country has its problems, ranging from lunatic energy policies to union thuggery. But it is equally undeniable that ever greater numbers of Australians enjoy levels of wellbeing the laconic Maluka of Mrs Aeneas Gunn’s We of the Never Never could scarcely have imagined when he promised the sweltering stockmen that the Christmas table at Elsey Station would groan with real ham and chicken, and hop-beer to boot.

There is, in other words, plenty to be grateful for — and gratitude, as Durkheim’s contemporary, Georg Simmel, so evocatively wrote, is “the moral memory of mankind”, the life-affirming reckoning that reminds us how much we receive and have left to give.

In these grudging times, may your Christmas be infused not with whinges and complaints but with the sense of thanks, and with the prospect, as often renewed as it is imperilled, of peace and prosperity, health and happiness, for all people of goodwill.