In a year best characterised as “plot by Dostoevsky, script by Groucho Marx”, it was perhaps fitting that the Senate celebrated Christmas by considering legislation that would have prevented Christian schools from teaching the doctrines of Jesus Christ.

If things got to that point, there was, no doubt, plenty of blame to spread around. Why the Turnbull government did not legislate to better protect religious freedom when it enacted the same-sex marriage legislation remains a mystery. Even more incomprehensible is why, having commissioned the review of religious freedom, it then refused to release its report.

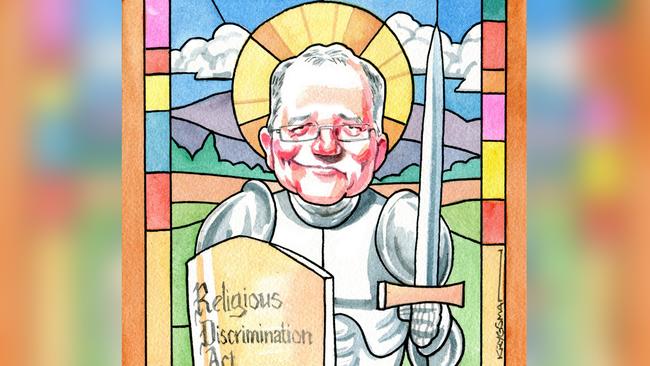

Somewhat belatedly, Scott Morrison committed yesterday to implementing the report’s recommendations, including a new religious discrimination act, and threatened to make religious freedom an election issue.

But that came only after Labor, exploiting the government’s slowness to act, launched a surprise attack with its proposal to repeal the current religious exemptions to the sex discrimination law, triggering the clash in the Senate.

Far from being a debate, that clash was a shambles in which logic traded at a deep discount.

Labor, for example, managed to contend both that repealing the current religious exemptions to the sex discrimination law was vital, and that doing so would cause no difficulties, as those exemptions played no practical role. How those claims could be reconciled was left hanging in a thicket of contradictions.

Observing the fiasco unfold, one could only conclude that an invisible enemy had been at work, eroding the foundations of rational thought in this country and replacing them with the intellectual equivalent of crack cocaine.

The victim, of course, was clarity. That choices must be made was presumably obvious to all; what was completely lacking was any sense of the principles that ought to guide them — and the Prime Minister’s announcement has hardly filled the gap.

The reality is that religious freedom has never meant absolute licence. No one recognised that more clearly than John Locke, whose A Letter Concerning Toleration of 1685 shaped subsequent conceptions of religious freedom.

Noting that it was “necessary above all to distinguish between the business of civil government and that of religion”, Locke argued that the state’s inescapable obligation was to ensure the security of its subjects.

As a result, while the state could not intrude on the “worship of the heart which God demands”, the outward actions of the body were “subject to the discretion of the magistrate” in so far as their regulation was required to preserve the peace and involved matters “indifferent to (superior) law”.

Religious freedom therefore conferred no right to injure others, engage in plainly abhorrent conduct or incite disorder.

Preaching that infidels were doomed to eternal damnation was consequently permissible. There could, however, be no justification for preaching that they should be summarily dispatched to their fate.

While those guidelines set outer bounds, it was always apparent that they left many areas of ambiguity that could only be resolved in the light of judgment. That those judgments would evolve in line with social norms was apparent, too. But that doesn’t mean that decisions about religious freedom should be made in a moral vacuum.

On the contrary, their starting point must be the recognition that faith is not a matter of taste: for an Orthodox Jew, wearing a skullcap is not a fashion statement. Rather, religious beliefs are commitments that give meaning to life and define what it is to live with integrity. And just as it is clear that being allowed to live one’s life with integrity is a supreme good, so it is clear that being prevented from doing so is a supreme harm.

Seen in that perspective, any legislation that forces people of faith to act against their deep conscientious convictions inflicts a moral harm akin to violence, and can be acceptable only when it is shown to be indispensable to prevent a harm that is even greater.

It is for that reason that John Rawls, perhaps the most influential political philosopher of the second half of the 20th century, argued that no social arrangement could conceivably be called just if it failed to place great weight on the demands of religious integrity.

Whatever the contentions made on its behalf, Rawls said, government action that trammelled the freedom to live in accord with one’s faith should be required to clear a high threshold of proof.

Nor should that burden of proof apply only to legislation that limits the freedom to hold a set of creedal propositions.

To live a life of faith is not simply a matter of beliefs. It is, as Ludwig Wittgenstein put it, to have “a passionate commitment to a way of living” that entails rites, rituals and social practices.

And perhaps the greatest commitment is the one that binds believers, through the act of remembrance, to their faith community’s past, and through the duty of instruction, to its future.

That is why the verb zakhar — “remember” — appears no fewer than 169 times in the Hebrew Bible.

It is also why the Pirkei Avot, which compiles the ethical wisdom of the rabbis, commands learning not for its own sake but so as to teach, and pass on to the young, “that which their fathers searched out”.

To restrict the right to undertake that teaching as faith commands is therefore a matter of the utmost gravity. And one might legitimately have expected every senator to appreciate that, just as they should have understood and thoughtfully applied the moral principles that bear on to the decision they faced, even if they disagreed on their implications.

Instead, Labor and the Greens were arrogant to the point of being flippant.

It was plain that had they succeeded, state schools would be allowed to teach that gender is a question of choice while faith-based schools risked legal action if they taught the opposite; but the concerns the faith-based schools expressed were simply dismissed out of hand.

So were the fears of many parents that repealing the exemptions would deprive them of the right to educate their children in line with their innermost convictions.

As for the government, it was perpetually on the back foot, having failed to prepare the ground for an issue that was certain to arise.

None of that will stop the senators from enjoying their Christmas break.

Nor will it deter Labor and the Greens from trying again when parliament resumes, as Morrison has finally recognised.

But the millions of Australians for whom this season is not simply an excuse for self-indulgence should demand better. If they are to get it, they will need to rely on much more than faith alone.