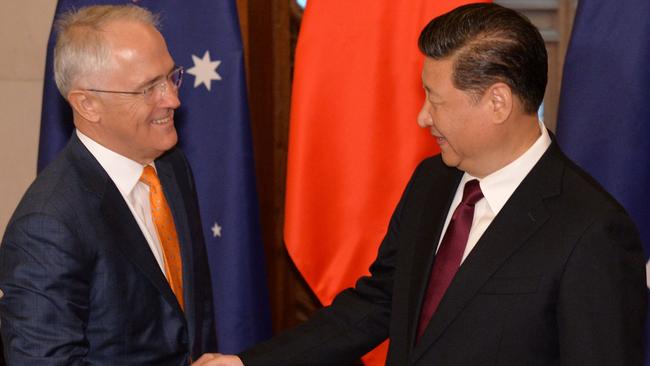

When Malcolm Turnbull visited China recently, he received an unpleasant, private message from the leadership there. If Australia were to undertake a freedom of navigation exercise in the South China Sea, there would be a very serious economic cost imposed on us by Beijing.

It was the standard Chinese bullying and it was abundantly clear in its import and consequence. Now this may well be a correlation and imply no causation, but Australia has not conducted any FON exercise in the South China Sea.

This is significant because when Tony Abbott was prime minister, the strong expectation throughout the Australian defence community was that we would conduct such an operation.

Kevin Andrews, then defence minister, gave a speech to a regional defence conference that seemed to prefigure it. Canberra’s Joint Operation Command looked close and hard at exactly how we might undertake such an exercise. The Americans, publicly and privately, have asked us to do so, and some Southeast Asians also have urged us on privately.

An FON exercise would involve sailing or flying within 12 nautical miles of an artificial island that Beijing has created in disputed waters. Under international law, artificial islands do not generate territorial rights. Therefore, whatever the merits of Beijing’s claims in the South China Sea, no such exercise would violate international law.

Despite some occasionally disgraceful laxity in terminology from government spokesmen, Australia has conducted no such exercises. The US has formally conducted two, involving ships, though very well-informed sources tell me there have been at least a couple of US flights that also have breached the 12NM limits but the US has not talked about these publicly.

The official position of the Turnbull government is that it has not decided to do such an exercise, nor not to do one. However, the expectation now is it won’t. Certainly it will not revisit the issue until well after the July 2 election.

All of this is important because of the widespread regional perception that the Turnbull government may have chosen not to go with Japanese submarines because of Chinese public and private pressure.

Let me hasten to say I believe this is an inaccurate perception. There is no evidence that the Turnbull government was intimidated by Beijing on this issue, despite the Chinese government at senior ministerial level demanding Canberra not choose the Japanese option.

Similarly, some participants in the debate within Australia, notably former Defence Department official Hugh White, argued explicitly that we should reject the Japanese option on strategic grounds because it might entangle us in the China-Japan conflict. This was the mirror of the consistent US argument that the Japanese option would have great strategic benefits for us and Japan and the US alliance system in Asia.

There is no reason to believe the decision was other than a technical one, really revolving around Japan’s lack of experience in this kind of defence export. It is also becoming clear that the Japanese, unlike the French, did not offer us the very best of their submarine technology. They offered us the Camry, we wanted the Lexus.

Nonetheless, the Turnbull government should actively manage these damaging regional perceptions of Australia being pushed around by China. It also should come to grips with the fact the way the whole sorry business played out has certainly severely damaged the Australia-Japan relationship, one of our most important relationships in Asia.

This is not an Abbott v Turnbull argument. You can make the case that Abbott is at fault for enticing the Japanese into a process they weren’t ready for and for giving them a de facto promise he couldn’t deliver politically. However, the handling of the relationship over the past six months by the Turnbull government has been a masterclass in ineptitude. Until the last minute, the Japanese were convinced they would win. The failure by the Turnbull government across the board to manage Japanese expectations is appalling.

The submissions to the competitive evaluation process were all in by the end of November last year. If it was so absolutely clear that the Japanese offering was far behind the French and Germans, the government would have known this by about mid-December. In all that time it couldn’t work out a way to manage Japanese expectations a bit more realistically and with a modicum of sophistication. This is a basic failure of statecraft.

But you would have to say more broadly that every single dimension of the public handling of the submarine decision has reeked of incompetence and clumsiness. This was less important than getting the decision right — and only time will finally tell on that score — but the process around it has been an astonishing mess. Now, any sensible Australian government would give the highest priority to repairing the relationship with Japan — generously, publicly, patiently, but with as much dispatch as possible.

The obvious thing to do is embark on a new program of intensified strategic co-operation with Japan, especially in the maritime sphere, in joint naval exercises, increased tripartite exercises with the US, common work on anti-submarine warfare and the like.

Such an initiative would have three tremendous benefits, two of which you wouldn’t even need to talk about publicly.

One, such strategic co-operation is a very good thing in itself. It has been an established practice between the two nations for some years and a notable acceleration of it would be more of a good thing. You could and should make a lot of this publicly.

Two, and most important, it would show the Japanese that we still love them, that we understand that our national processes were confused and disorienting and often incoherent in our dealings with them, but we care deeply about the Japan relationship and want it to move forward. You could say a lot about that to the Japanese privately, given that no government in Canberra could be expected to acknowledge publicly how incompetent the whole Australian process has been.

And three, such an initiative on Canberra’s part would clearly demonstrate that we are not being pushed around by Beijing. The Chinese government does not want closer strategic co-operation between Australia and Japan and has made this abundantly clear. You wouldn’t need to talk about this at all.

Our national security bureaucracy is in fact hard at work considering such options. There is continuing dialogue with Japanese agencies about accelerated efforts. The Japanese Defence Ministry houses the people who feel most bruised by it all. But the Japanese National Security Secretariat, which reports to Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, is very open to such ideas.

Consider my astonishment, then, when I approached the Turnbull government with all this good news about the good work the bureaucracy was preparing on its behalf to repair the Japan relationship, only to be told that no such project exists, that there are to be no special initiatives for Japan, that anything that is going on in this area is merely continuity with pre-existing practice and does not involve the possibility of any gestures or new programs by us. Que?

Don’t you dare accuse us of good policy, seems to be the Turnbull government’s response. What on earth could explain this bizarre approach? There are only two possibilities, really.

One is that the government must believe that any hint of any new gesture would be an admission that something had gone wrong. And whereas every sentient human being on the planet who has the slightest knowledge of Japan-Australia relations knows that a great deal has gone wrong, the government is apparently determined to deal with reality by denying reality, never a winning proposition for a government.

The only other possibility — and I don’t advance it as anything more than a possibility consistent with the facts — is that the Turnbull government could be asking itself the most debilitating question of all: How will this play in Beijing? If that is the case, having asked the question, it is apparently coming up with the worst possible response. I don’t assert that is happening. It is merely a possibility consistent with the facts.

Sadly, anybody trying to decipher the government’s strategic policy is like a defence engineer who has captured a bit of the enemy’s kit and is trying to reverse engineer their way to discovering the elusive inner logic of what looks very much like the outer confusion.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout