India under Narendra Modi could be Australia’s next China

Australia has a great deal to gain from Narendra Modi’s economic ambitions.

It is often said that the three things which strike a new visitor to China are the scale, the cultural continuity and the distinctiveness of the way things are done.

The same is at least equally true for India, though the widespread use of the English language has sometimes obscured what a massive undertaking in Asian democracy, economic growth and emerging strategic power India will embody if it gets anywhere near its ambitions.

The sheer scale of the undertaking is truly staggering.

Indian policymakers believe that 300 million people will move from the countryside to the cities between now and 2050.

Yes, 300 million people.

This will necessitate something like 100 new cities.

There are huge growth corridors planned between Delhi and Mumbai, Bangalore and Chennai, Amritsar and Kolkata. There are massive development plans for the Orissa and Andhra Pradesh coast.

I am told that for the specific infrastructure alone planned for the next decade, India will need 650 billion tonnes of cement. Steel production will go from 80 million tonnes a year now to 300 million tonnes a year by 2020.

Some Western greenies may have decided that they don’t like economic development, but for poor people there is absolutely no other way out of poverty.

India desperately needs this development. It is approaching a moment of truth. There are many reasons why India’s economy has massive potential growth locked up in it. One is the so-called demographic dividend. Every year for the next 10 years, about 20 million Indians will enter the labour market. India’s population is much younger than the population of any Western nation and much younger than China’s population. This tremendous growth in the labour force means that the next decade could yield utterly transforming economic growth.

And if that growth and development doesn’t arrive, it will yield hundreds of millions of people destined to a life of poverty.

India’s last prime minister, Manmohan Singh, of the Congress party, was the father of economic reform as finance minister in the early 1990s. He unexpectedly became prime minister a little more than a decade ago and had two terms. His first term continued the momentum of economic reform and set up further Indian economic growth.

But his second term was paralysed by infighting within the Congress party, much of which turned away from Singh’s reform program. Although his term in office can also be interpreted as him holding the line against those who wanted to positively undo reform, little new reform was accomplished in his last years.

Instead his government concentrated on stimulating the demand side of the economy by endless fiscal stimulus, much of it transfer payments targeted at what the Indians call vote banks, specific communities.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s historic task now is to unlock as much of the constraints on India’s supply side as he can.

The fallout from the continued fiscal stimulus of the half decade before Modi came to office, plus the lingering aftertaste of the global financial crisis, mean that Indian banks and corporate balance sheets are not robust enough to finance the massive infrastructure that Modi is committed to. He sees the provision of better infrastructure as the key supply side reform he can make.

So he has scoured the world for development money for India. The Japanese plan to invest hundreds of billions of dollars in India. The South Koreans, the Americans and even the Chinese also have big plans. Australian pension funds and institutional investors generally are starting to look seriously at India.

With the intense global search for yield, Indian infrastructure, although certainly not without risk, offers a great deal. The high-growth, substantial economies will not be in the West. They will still be mainly India and China, and to some extent Indonesia.

But Modi has also decided pragmatically that for a year or two at least the Indian government will have to pay the price for infrastructure directly. So Modi’s budget contained huge infrastructure allocations.

All of this can transform our world. It could transform our world just as much as Chinese economic growth has over the last 30 years.

Thirty years ago I was a correspondent in Beijing. I remember the Australian ambassador to China at the time, Dennis Agrall, telling me that China would eventually be as big an opportunity for Australia economically as Japan had been. I thought at the time he was wildly overestimating things. I was wrong.

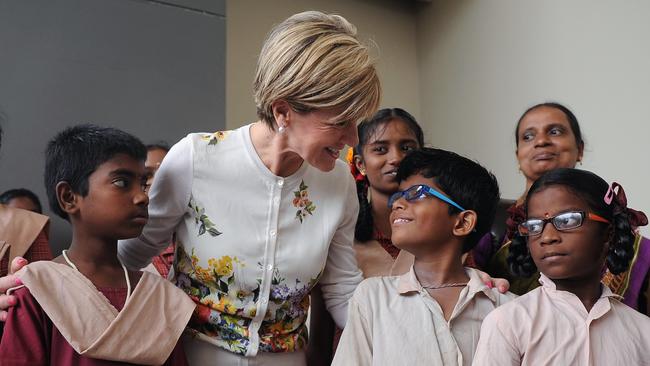

Australia needs profoundly to be alive to the Indian possibility. This is actually something that Tony Abbott, Julie Bishop and Andrew Robb get much more deeply than the community as a whole does, even the business community, with honourable exceptions. India is already our fifth largest export market and trade is worth $15 billion. This is nothing to be sneezed at but does not remotely compare, as yet, with our trade with China, which is 10 times as great.

Australia is also deep in negotiations towards a free trade agreement with India.

Both prime ministers committed to getting it completed by the end of this year. That is very ambitious. But ambition is no bad thing in this field.

About 75 per cent of our exports to India today are coal, gold and copper. There will be massive Indian demand for Australian coal. Even though India has big coal reserves of its own, it will be years before its mines are sufficiently up to speed to meet its growing demand.

Soon enough — within weeks or a couple of months at the most — the arrangements concerning the uranium safeguards agreement will be finalised and we will in due course export uranium to India for its growing nuclear energy industry. Over time there will be massive opportunities in the export of natural gas.

The one big gas contract that India signed came at the height of the gas price boom, so Australian gas has the reputation of being unduly expensive. Certainly Australia has an uncompetitive cost structure and will need to address that over time. But West Australian Premier Colin Barnett visited India a few weeks ago and came away convinced that West Australian gas would be competitive in India within a couple of years. The potential for a long-term energy partnership of the type that Australia had with Japan is enormous.

Commodities will dominate our trade with India for a long time, as we have the opportunity that we had previously with China and Japan to provide a big chunk of the resources needed for Indian national development.

But already India is changing Australia, and for the better, and the opportunities beyond resources are enormous.

Of Australia’s population of 24 million people, about a half million have an Indian background.

There are 46,000 Indian students in Australia, a number that this year represented an increase of nearly a third on the previous year. Nearly a quarter of a million Indian tourists visited Australia last year.

In the long run, beyond resources and infrastructure, the opportunities offered by agriculture and training, and indeed most services areas, are vast.

Australia can not only make money out of India’s growth, it can make a serious contribution to human welfare.

Modi understands that he must not lose the support of the poor. His government has brought an additional 130 million people into the formal banking sector.

This kind of monetisation of previously subsistence agricultural communities is the once-in-history chance to change a people forever.

India will need to train 500 million people over the next decade.

Australia has world-class expertise in training and agriculture. The potential for Australian companies and institutions to earn honest income, and at the same time contribute to the betterment of the human race, in these two endeavours in India is enormous.

Beyond all this, there is a huge geostrategic common agenda between the Modi and Abbott governments.

The challenge and opportunity that India offers to Australian policymakers are just as great as that which China and Japan previously offered.

Are we up to it?

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout