GREEK Prime Minister George Papandreou has balls. And his decision to call a referendum on the austerity program is hardly irrational. True, it is a gamble, and a risky one. But, like Paul Keating in 1986, he has confronted Greece with its banana republic moment, and challenged it to rise to the threat it faces. Far from expressing dismay, European leaders should have endorsed his call.

Doubtless, in deciding to hold the referendum, Papandreou will have recalled Pericles's oration for the dead in war, where the statesman contrasted the Athenians with their neighbours. The Athenians, he said, had no monopoly on bravery; but their neighbours "are brave out of ignorance". The Athenians, in contrast, "are capable at the same time of taking risks and of estimating them beforehand". That was the essence of courage; for "the man who can most truly be accounted brave is he who knows what is sweet and what is terrible, and goes undeterred to meet what is to come".

But Papandreou's decision is as much about realism as heroics. To begin with, Papandreou's own party discipline is fraying badly, with at least two Socialists voting as independents. The dissidents' position is strengthened by the fact the austerity measures are starkly at odds with the program Papandreou's party took to the 2009 elections.

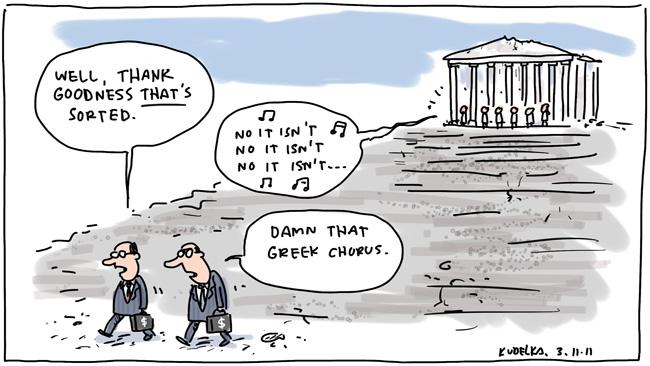

At the same time, he faces constant harassment from the conservative opposition, despite its instrumental role in the accounting manipulations that brought Greece into the euro.

And he also confronts prolonged strikes, with ongoing violence incited by self-styled anarchists and the hard Left.

The referendum, if it goes ahead, is his best chance of getting his own party into line. And it will force the opposition, which has always insisted it is pro-euro, into a box. Yes, the far Left will claim there are alternatives. But by obliging them to be spelled out, Papandreou hopes they will be shown to be hardly credible: rather, under any scenario, Greece must face a lengthy period of austerity and structural reform.

The referendum will also change Papandreou's bargaining position relative to his eurozone colleagues. They have never been willing to face the reality of Greece's position: it needs an assured window of three to five years in which to adjust. The referendum could make them more willing to provide Papandreou with tangible benefits he can offer the electorate.

None of this ensures Papandreou's gamble will pay off. Indeed, the opinion polls are not encouraging. But if Greek public opinion rejects the package, there is no way it could have ever been sustained, as mounting opposition would have rapidly destroyed Papandreou's wafer-thin majority. And if he loses, it is certain that he would also have faced defeat in the general elections scheduled for 2013, at which time the task would barely have been begun.

In making their choice, the Greeks need to address issues that go far beyond the euro. Rather, they hinge on whether Greece modernises its economy or falls back into the politics that have repeatedly brought it to the brink of disaster.

Those politics have deep historical roots. For even more than the other countries of southern Europe, the 19th-century bourgeois revolution passed Greece by. And even at the end of World War II, Greece remained trapped in the past, with simmering tensions that exploded in the savage civil war of 1946-49.

While a semblance of normality was re-established in the 1950s, politics, centred on the rival Karamanlis and Papandreou dynasties, was mired in patronage and corruption. Moreover, with the Cold War ever present, the army remained a key player in society, ultimately seizing power in the colonels' coup of 1967.

The colonels may have been anti-communist, but they were anything but pro-market. Heaping misjudged policy on misjudged policy, by the end of their rule in 1974 they had brought Greece to its knees. Unfortunately, the conservative Karamanlis government that succeeded them was scarcely better, virtually doubling the size of the state sector so as to shore up its base of support.

And its successor, under Andreas Papandreou (son of the previous centre-left prime minister and father of the current PM), took state intervention to new heights, as well as greatly expanding public spending.

In a country where government had scant legitimacy, it was impossible to get electoral support for the taxes needed to fund those expenditures. The predictable result was periodic balance of payments crises, leading to a cycle of devaluation, accelerating inflation and renewed pressure on the drachma. The euro, however defective its design, brought that cycle to an end. But it did not, and could not, resolve any of the underlying problems, any more than it could in Italy, Portugal or Spain.

As a result, the crises have taken new form, as bloated public sectors, distorted labour markets and widespread corruption undermined competitiveness and made it ever more difficult to service public debt.

That is the legacy Papandreou inherited. And as much out of necessity as of choice, he has sought to tackle not only the symptoms but at least some of the causes. Whether he will succeed is highly uncertain; but in the birthplace of democracy, he is right to put the decision to the people.

Of course markets would have preferred the devil they think they know, in the form of last week's agreement. And so would Angela Merkel and especially Nicolas Sarkozy, who viewed it as a triumph. But they are as much discomfited by their own reliance on elite opinion, rather than popular support, for the policies they have pursued as they are by the uncertainty Papandreou's decision creates.

Locked in mutually assured distrust, the eurozone may therefore still descend into mutually assured destruction. But the best hope for what comes next must lie in securing a genuine popular mandate, rather than in yet more top-down solutions from discredited elites.

That requires a greater degree of faith in the democratic process than the proponents of European integration have ever accepted. But as Sophocles writes in Phaedra, "truth is always the strongest argument". Good on Papandreou for taking it seriously.

And finally, vale to Roger Kerr, executive director of the New Zealand Business Roundtable, who died last week. Long after the rest of us are reduced to footnotes, he will be remembered as a fearless and scrupulous advocate for sensible economic and social policies and for the prosperity of his country: and most of all, as a passionate believer in reasoned argument and the power of the truth.