TOMORROW the nation goes back to work with no clarity whatsoever as to the government's fiscal strategy. Yet exactly a year ago, the Prime Minister was unambiguous.

Here is what she said in the lead-up to Australia Day last year: "One thing you can see from around the world, it is the right time for governments to be clear on their fiscal strategies and we are clear on ours."

"My firm conclusion is that handing down a budget surplus in May is the right call in the present economic circumstances."

Having now abandoned that commitment, the government, instead of putting any alternative in its place, has focused on finding excuses for its backflip.

Spending, it claims, has been squeezed so hard you can hear the pips squeak, but slow world growth has held back revenues. Simply put: "The international economy ate my homework."

That explanation doesn't stand up to scrutiny. And even worse, it entirely misses the lesson the advanced economies' difficulties make clearer every day.

That lesson is that once fiscal sustainability is lost, restoring it is an immensely costly and painful process: indeed, as with disinflation in the 1980s, it is far costlier than had been originally believed.

Moreover, the less credible governments' fiscal strategies are, the greater are those costs, making it even more important for governments to articulate and respect sensible fiscal principles.

A starting point must be honesty about the fiscal situation and its causes. Here the relevant facts are straightforward.

In 2008-09 and 2009-10, Labor massively increased government spending, taking it to a higher share of GDP than at any time since 1993-94. That surge was meant to be wound back once the economy recovered; but though growth was well above trend by 2011-12, the increase was never reversed, with new spending programs being ramped up as stimulus measures were phased out.

As a result, since Labor was elected, per capita government expenditure has increased by 3 per cent a year in real terms, more than double the rate at which it grew under John Howard.

Financing such a binge was never going to be easy. But the 2008-09 budget was not unreasonable in estimating it would take revenues six years to catch up. So prolonged a deficit, however, didn't suit the government's electoral strategy.

With the 2010 election looming, it announced it would "bring this budget back to surplus in three years, three years early", thanks to an 11.8 per cent surge in expected revenues.

That forecast surge was never plausible: it involved tax collections increasing more rapidly than at any time since 1986-87, when an overheating economy and raging inflation produced a 13 per cent increase in revenues.

No surprise then that actual revenue growth has fallen well short of that forecast: and with spending still at record levels, that the budget remains in deficit and net public debt continues to rise.

The government therefore has no one to blame for its fiscal woes but itself. To say that, however, hardly means one should ignore the international situation. On the contrary, that situation makes the government's lack of a credible fiscal strategy even more lamentable. Here, too, the facts are simple: recovery from the global financial crisis has been far slower and more uneven than expected.

In April 2010, for example, the International Monetary Fund forecast that by 2011 the advanced economies would be growing at 2.4 per cent; instead, with growth at 1.6 per cent, the advanced economies' GDP is 10 to 15 per cent below its long-term trend.

In part, that shortfall reflects forecasters' underestimate of the extent to which the imbalances before the GFC had distorted the capital stock, for instance by inducing over-investment in the construction industry and in all the activities that depend on it.

As that capital was written off and production capacity decommissioned, the level of output the advanced economies could achieve was reduced, with some studies pointing to a fall as large as 9 per cent of GDP.

But to make matters worse, the fiscal position of most advanced economies proved both weaker and more vulnerable to sharp downturns than had been thought.

Seemingly strong fiscal positions crumbled as hidden liabilities emerged, including the cost of bailing out banks and of guarantees on misjudged infrastructure projects. Merely stabilising those fiscal positions, much less restoring long-run sustainability, has turned out to be extremely costly in job losses and forgone output, especially in economies with bloody-minded unions, rigid labour markets and little or no wage flexibility.

The world economy is, in other words, paying dearly for past policy errors - precisely as occurred with runaway inflation in the 1980s and early 90s.

That restoring fiscal sustainability involves very high costs is a lesson that should resonate in Australia, all the more as the Coalition governments in the states are grappling with those costs every day.

Much like Jeff Kennett in 1992, Campbell Newman has been left with Labor's fiscal mess: not merely the sheer growth in Queensland's public debt but the fact that so much of that debt was wasted on assets, such as the $3 billion Western Corridor Recycled Water Project that audits have shown to be virtually worthless.

Just as Kennett had to take harsh spending decisions to bring debt under control, so Newman has had to make cuts that are understandably unpopular.

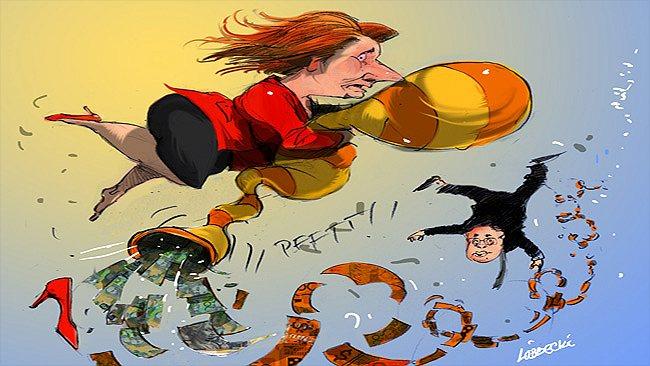

There is, however, a crucial difference between Kennett's position and today's Coalition premiers: Kennett received more than tacit support from the Keating government, which recognised Australia's stake in repairing public balance sheets. But Julia Gillard and Wayne Swan are not in that class.

The national interest means little to them when there are cheap points to be scored. And rather than get their own house in order, they find it far easier to burn down the house next door.

Little wonder then that the Gillard government's fiscal credibility is in tatters. But however bad that may be, the real pity is where it leaves ordinary Australians: exposed to high adjustment costs in future.

And with no sign of the government learning the lessons of international experience, it is only a matter of time before those costs come home to roost.