ACCORDING to Fred Chaney, the rioters at the Aboriginal tent embassy have no more in common with most Aborigines than the Cronulla rioters have with most other Australians.

There is an obvious sense in which Chaney is right. But there is also a fundamental difference: at Cronulla, law-breakers were arrested and charged in large numbers; at the tent embassy, they were not.

Nor is there any question as to why this is so: the tent embassy rioters were Aboriginal, or claimed to be; the Cronulla rioters were not.

And the special treatment does not end there. That the tent embassy is inconsistent with ACT planning laws and restrictions on land use in the parliamentary triangle is uncontested; yet the ACT authorities, unfailingly harsh in enforcing planning regulations on ordinary folk, turn a blind eye.

It is impossible to reconcile these differences in treatment with the rule of law. Its basis is the law's equal application: no one -- white or black, man or woman -- has a special right to threaten violence or engage in assault. Rather, regardless of race, creed or gender, we are all deemed capable of taking responsibility for our conduct. And if that conduct violates the law, we should expect to be held to account.

That ought to apply to the protesters at the Aboriginal tent embassy exactly as as it applies to everyone else.

But that is not the message the Prime Minister and the ACT police sent. Though they have now been forced to backpedal, their message was that the protesters should not bear the full weight of the standards all other Australians must respect. This is deplorable in itself; but most important, it is the last thing Australia's Aborigines need.

This is not merely because it is abhorrent to suggest indigenous people should be treated as minors, whose behaviour must be excused if not condoned. It is also because it is notorious that Aboriginal communities suffer from endemic violence and lawlessness.

Take the young girl who the day after the riot burned an Australian flag. She was "heaps angry" because "my grandparents, aunties, uncles were all murdered, raped, sexually abused". Her claims may be exaggerated. Yet it is well-known that, in the words of a major study of Queensland Aboriginal communities, there is widespread "fighting, child abuse, infant rape, rape of grandmothers, spouse assault and homicide". Little wonder anthropologist Peter Sutton, returning to Aurukun where he had spent much of the 1970s, found, "like the Australian war graves at Villers-Bretonneux", a cemetery with "painted crosses, many of them fresh, stretching away seemingly for hundreds of metres", the devastating legacy of death from violence.

Faced with those horrors, indigenous people, perhaps more than any other Australians, merit the comfort of knowing that regardless of the assailant or the victim, assault will lead to a police response that is swift, certain and impartial.

This is not to claim that law enforcement is the entire solution to the plight of indigenous communities. But there can be little doubt that an active police presence and timely intervention in curbing rowdy behaviour are crucial in convincing potential offenders that lawlessness will not be tolerated. And that in turn reduces both the frequency of crime and the eventual extent of incarceration.

That is important because Australia's Aboriginal communities have incarceration rates that are appallingly high. But as Harvard professor William Stuntz, a giant in the field of criminal justice, famously concluded from his study of African-Americans at high risk of offending, incarceration rates are greatest precisely where the police presence is weakest and deterrence least vigorously applied. And those are the communities that also bear the greatest costs from violence itself, from the anguish it causes and from costly, though often futile, attempts at avoidance.

The mayhem at the tent embassy therefore should have been an opportunity to show that lawlessness cannot and will not be accepted: much as happened at Cronulla. Instead, a double standard was applied; and by signalling tolerance of crime, the protection that double standard offers the guilty will come first and foremost at the expense of their innocent neighbours.

Nor should anyone doubt the incident's corrosive effects on race relations. Allowing the perpetrators to get off scot-free would cement the impression of Aboriginal special treatment, strengthening resentments that, however unspoken, can only grow as repeat performances occur.

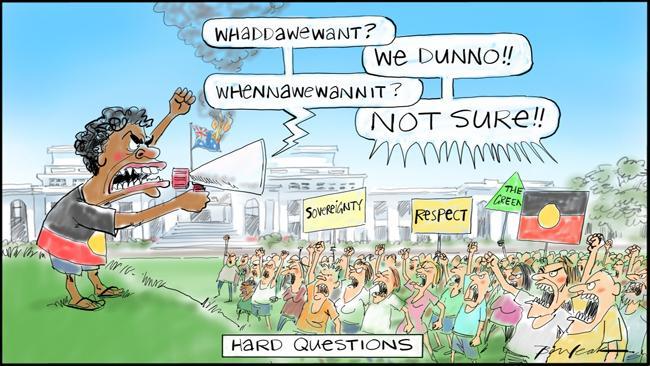

At the same time, the special treatment legitimates a victim culture richly on display in the protesters' claims that, far from being responsible for what occurred, they were "manipulated".

As those consequences play themselves out, the protesters will have achieved their goal: they will have fanned the very hostility that underpins their separatist fantasies. There is only one way to prevent that eventuating: ensure all those who broke the law on that day are speedily charged and brought to trial.

But it is not easy to be optimistic that will happen. For, as in so many areas, there is a contradiction at the heart of the government's indigenous policies. On the one hand, it has shown commendable conviction in pursuing the intervention. At the same time, however, it has wanted to appease the radical fringe and its soft liberal supporters, whose policies have contributed so much to today's failures. The result, also highlighted by the proposed constitutional amendments, is a morass that threatens what progress has been made.

That a Gillard staffer, in an attempt to embarrass the Opposition Leader, played a role in the events only makes that contradiction all the more stark. Tony Hodges is, by all accounts, an intelligent person. He would have known what he was doing in conniving with Unions ACT secretary Kim Sattler to score cheap points at Abbott's expense. That he should have thought to do so suggests a pathological atmosphere in Gillard's office and in our politics. Yet its costs will be high: for this is one of area where there has been a genuine degree of bipartisanship; and it is difficult to think of any area where continued bipartisanship would be more important.

Ultimately, the Australia Day riot was trivial in scale and significance. Properly handled, it would have faded rapidly from the national consciousness.

It is the failure to do so, and the contradictions that exposes, that are both the great danger and the real disgrace.