When the first Abbott government ministry was named after the Coalition’s election victory in 2013, the last person listed in descending order of importance was Nationals MP Michael McCormack, named as the “parliamentary secretary to the minister for finance”.

That was less than five years ago, and yesterday the former newspaper editor and MP for Riverina in southwest NSW vaulted to No 2 on the ministerial list as Deputy Prime Minister and Nationals leader.

Looking like a vacuum in the space left by the larger-than-life Barnaby Joyce, just eight years after entering parliament, the see-through McCormack has become Deputy Prime Minister and the man to hold the reins when Malcolm Turnbull is absent.

But this is not because of some meteoric rise or undeniable brilliance that has pushed McCormack to the top of his party and into the most senior and secret councils of Australian government; it’s a result of paucity of talent within the Nationals and, unfortunately, a symptom of a wider diminishing experience and talent in federal politics.

The churn of leaders, ministers and MPs on all sides since the fall of the Howard government and the beginning of a dismal decade of political power plays and voracious publicity has dramatically reduced the experience of our federal parliamentarians and the quality of government.

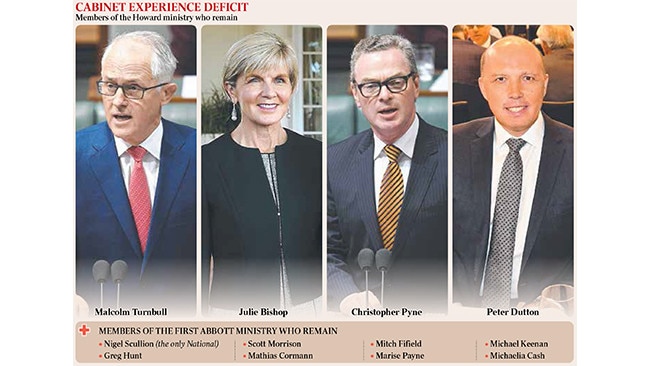

There are now only four Coalition ministers with experience from the Howard government, all Liberals: Turnbull, Julie Bishop, Christopher Pyne and Peter Dutton. There are only 12, including those four, from the first Abbott ministry of 2013 in frontline positions. The other eight surviving Abbott ministers are Nigel Scullion (the only National), Greg Hunt, Scott Morrison, Mathias Cormann, Mitch Fifield, Marise Payne, Michael Keenan and Michaelia Cash.

In 2013, even after seven years in opposition, Tony Abbott, who had become leader of the Liberal Party after 15 years in parliament and prime minister after 19 years’ service, named 22 ministers and parliamentary secretaries who had served under John Howard.

After running on a record of “experience” in government and demanding Labor give government “back to the adults” in 2013 the Coalition is looking decidedly short of long-term experience.

Since Turnbull became Prime Minister there are or have been sitting on the backbench a former prime minister, a former deputy prime minister, a former treasurer and more than a dozen former senior and junior ministers.

The biggest single loss of Coalition ministerial experience was after the Turnbull removal of Abbott as prime minister in 2015 when Abbott, Joe Hockey, Kevin Andrews, Eric Abetz, Ian Macfarlane and Bruce Bilson — all Howard ministers — were dumped to the backbench.

Joyce’s move yesterday from the frontbench to the cockies’ corner of the Nationals backbench in the House of Representatives is just another bleeding of political talent and experience from the Coalition and the body politic.

But McCormack’s rise to leader after less than 10 years in parliament and five years on the frontbench is not an aberration: Joyce himself was elected in 2016 as Nationals leader less than 10 years after entering the Senate and less than three years after being elected to the House of Representatives. In contrast his predecessor, Warren Truss, was in parliament from 1990 and elected leader only 17 years later.

Instead of long-term ministries building experience in governance, the turmoil of leadership challenges creates a ministerial turnover that leaves governments in exile sitting on the backbench and ripe for retirement and further loss of experience.

On the Labor side, Mark Latham, Kevin Rudd, Julia Gillard and Bill Shorten were elected Labor leader with barely 10 years’ experience or much less, and with virtually no experienced ministers to call upon.

Rudd, who joined parliament the same year as Gillard, became prime minister in less than 10 years, and Gillard replaced him when she had barely more than 10 years’ experience.

When Rudd was elected in 2007 — after Labor was in opposition for more than 11 years — there were only two MPs with any experience in the former Keating government he named in his first ministry: John Faulkner and Warren Snowdon.

Today, after five years in opposition, there are 15 members of the Labor frontbench, including Shorten, who can boast relatively long ministerial experience in the Rudd and Gillard governments, including Anthony Albanese, a former deputy prime minister, Tanya Plibersek, Penny Wong, Chris Bowen, as a former treasurer, Tony Burke, Richard Marles, Joel Fitzgibbon, Mark Butler, Mark Dreyfus, Jenny Macklin, Brendan O’Connor, Julie Collins, Catherine King, Jason Clare and Ed Husic and Shayne Neumann as parliamentary secretaries.

It is now Labor’s strategy to portray the Turnbull government as being in chaos, divided and unable to govern as ministers are pushed aside or forced to resign.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout