LOREE Rudd remembers her brother Kevin sitting dreamily in the cow shed while the rest of the family tackled the more mundane chores of animal husbandry. “He preferred to design castles out of the cow feed,” Loree once told essayist David Marr.

Was it possible, even then, that the young romancer destined to be our 26th prime minister was working on an early version of the Seamless National Economy Agenda?

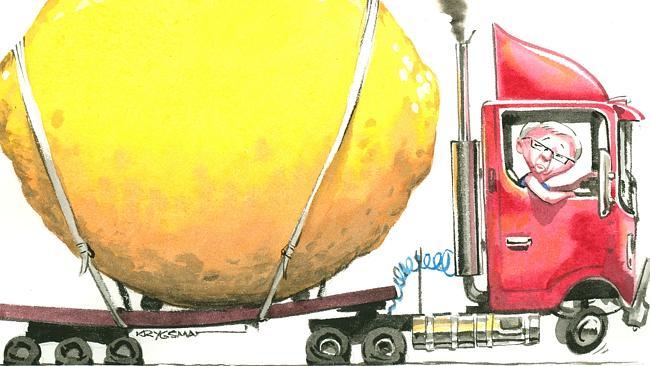

An improvised fortress constructed from stockfeed that collapses under the slightest pressure is an apt metaphor for the National Heavy Vehicle Regulator, a late-developing legacy of Rudd’s dream of coast-to-coast harmonisation.

The NHVR will save the economy $1.5 billion or $2.4bn a year, depending on which of Anthony Albanese’s press releases you pick. It would take truck regulation away from the Mensa-challenged mutton-heads assumed to be in charge of the states and hand it to an omni-benevolent commonwealth bureaucracy.

Albanese was tweeting like a clucky dad two weeks ago when the NHVR opened for business. “After years of confusion and costly red tape, all trucks, buses and other vehicles weighing more than 4.5 tonnes come under the new Heavy Vehicle National Law,” he wrote in a press release.

Sadly, however, the launch of the national truck regulator - 13 months behind schedule - has been a colossal disaster, as Albanese could have predicted if he had had his ear to the ground.

The transport of oversized and overmassed (OSOM) loads has been virtually frozen. The mining and construction industries have been hit particularly badly. Operators, drivers and contractors are seething. The streamlined, seamless, one-stop shop is a lemon.

Under the old state-run system, OSOM permits could be issued in a matter of hours, but by the middle of last week well over 2000 applications for special load permits had been lodged, but only 250 had been issued.

Civil Contractors Federation chief John Stewart said on Friday: “The heavy machinery and materials many companies need to operate are grounded due to ridiculous bureaucratic red tape and incompetence.”

The theoretical benefits of harmonised state and federal truck regulations are clear. But the potential pitfalls are great, and the transition costs daunting.

The easy steps of economic integration were taken long ago in the journey of federation. Rudd’s Seamless National Economy Agenda was forced to look for smaller targets.

In any case, the Canberra bureaucracy is hopeless at practical tasks (as home insulation royal commissioner Ian Hanger is about to discover) even when it decamps to Brisbane as a sop to the Queensland government.

The NHVR’s early clunky moves betrayed its public service parentage. Industry would be consulted, working groups established, expert panels appointed and stakeholders engaged.

A newsletter, the Road To Regulator, kept readers updated with the gusto of Pravda lauding Stalin’s Five Year Plan. The inaugural industry consultation forum in 2010 “was declared a success”, demonstrating the NHVR’s “commitment to genuine stakeholder engagement”.

By May 2012, however, with less than eight months to launch day, there were signs of panic. Chief executive Richard Hancock admitted there were “a range of outstanding issues” still to settle.

Queensland had a new government, and its new Premier, Campbell Newman, was asking questions. The state’s permit-issuing system was the best in the country. Queensland’s bureaucrats and transport operators had become adept at bypassing red tape and finding short-cuts through the system. Why reinvent the wheel?

It was becoming clear that the NHVR would not be up and running by January 1, 2013, and the launch date was put back to July. Last May, it was put back again until September.

“I think everybody wants to make sure that when it goes live that everything is ready,” said Hancock.

In August, Hancock revealed there were “integration issues” with the new IT system and the launch was put back another month. October 1 came and went. Then, shortly before Christmas, Hancock told Trailer magazine: “We can confidently say we will be ready on 10 February.”

His confidence was misplaced. The new system, years in the making, was overwhelmed as soon as it went live.

Facebook’s frown deepened. “WTF???” posted Julie, four days after the scheme began. “We’ve been trying since Monday for one OSOM permit many many phone calls including wrong advice from them.”

A late-evening text from a former colleague 12 days ago alerted Newman to the emerging disaster. The Queensland government told Canberra it was stepping in. Newman describes the new system as “a bucket of custard” and is threatening to pull out of the NHVR altogether if the problem is not fixed.

On Friday, the Victorian government followed Queensland in reopening its own licensing operations.

Hancock, who has become a master of understatement, admits: “There have been challenges in adjusting to the new national law.”

Diesel News editor Tim Giles says parts of the heavy haulage industry are at a standstill.

“The first thing the NHVR has had to do properly is a dismal failure,” he wrote last week. “The rest of the trucking industry are losing confidence fast as to whether Hancock and his team can do the job at all.”

The OSOM debacle has brought other grievances to the fore. The industry is obliged to pick up $135 million of the cost of running the NHVR, $60m more than it paid under the old system.

The NHVR has been working on policy safety proposals that would require expensive investments in GPS technology for questionable results. The regulator is making decisions beyond its pay grade.

The “teething problems” - as the regulator likes to call them - may yet be sorted out. The notion that centralising truck regulation might constitute genuine micro-economic reform, however, seems fanciful.

It looks instead like a folly devised by a “man of system”, as Adam Smith might have described Rudd and many of his ministers.

“The man of system seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess board,” wrote Smith.

The man of system falsely considers that each chess piece moves only according to his hand. In reality, it has “a principle of motion of its own, altogether different from that which the legislature might choose to impress upon it.”