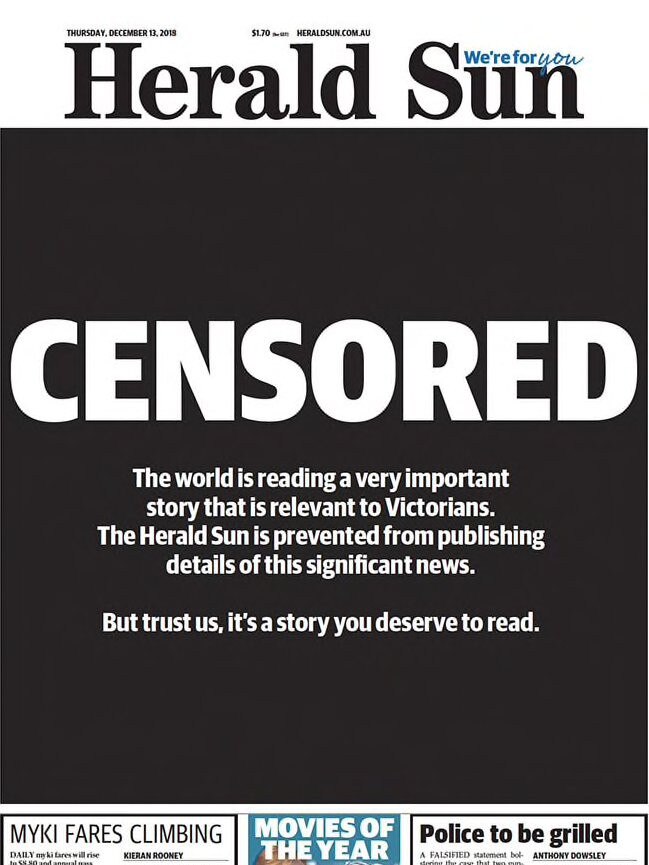

On December 13 last year the front page of the highest-selling newspaper in the nation, Melbourne’s Herald Sun, was mainly black. It looked like the publication was a visual dirge for some fallen hero. It was, in fact, lamenting the death of transparency in our legal system.

The word “Censored” broke up the page with a screed underneath reading: “The world is reading a very important story that is relevant to Victorians. The Herald Sun is prevented from publishing details of this significant news. But trust us, it is a story you deserve to read.”

The news, as everyone now knows, was the conviction of Cardinal George Pell on child sex charges. People were freely reading about this court decision overseas while Australian media was banned from reporting it.

On social media there was consternation. Educated and informed people posted expressions of anger, suspicion and frustration about this news being suppressed. There were claims that Pell was being given special treatment because of his status.

Extraordinarily, citizens of this country were not to know about this verdict nor the stalemate at a previous trial when a jury could not be convinced over the same charges against Pell. There was an impervious pall over the entire Pell proceedings.

Inside the media, while news organisations and their lawyers were frustrated and actively considering all their options, there was less surprise at the existence of the suppression orders because experienced journalists are used to the imposition of such orders and the way they work. Almost everyone in the media knew of the verdict and the reason for the suppression — to prevent the contamination of another trial on similar charges.

As we all found out this week, the suppression order on the December verdict was lifted when the second case fell over. News organisations had been preparing for this eventuation for weeks but still, such was the gravity of the conviction, there was astonishment and drama when the news broke.

There was never any doubt we were all going to know the relevant facts eventually but seldom, if ever before, has such a newsworthy verdict been held from public consumption for so long, especially while international interest was being sated.

Unsurprisingly, this has prompted renewed debate about suppression orders. Even before the verdict was suppressed, much of the Pell trial evidence was banned from publication as, it must be said, is often the case in sexual abuse trials.

Law Council of Australia president Arthur Moses is pushing for a review of suppression laws. “At its core, this issue involves striking the right balance between open justice, including the public interest in court reporting, and the right of the individual to a fair trial,” he said.

“While suppression orders and closed hearings are appropriate in particular cases, such as family court hearings and when hearing evidence from child witnesses, or where an accused may otherwise be unable to obtain a fair hearing, their need should always be balanced with the broader public interest in open justice.”

Borders have always played havoc with suppression orders. Back in 1999, while an Adelaide court was hearing gruesome evidence about the Snowtown murders, most South Australians were oblivious to the horrors; that is, until they travelled interstate and picked up the newspapers in the airports.

In such a way news, of course, travelled — and instead of reading it in their own papers or hearing it on local television or radio, South Australians picked up potted versions from friends. National media programs had to tailor their bulletins to ensure they didn’t breach SA law.

In the digital age, these types of complications have made suppression orders more difficult to enforce and more redundant in practice. The internet and social media know no boundaries and often show scant respect for laws of defamation or contempt.

In such circumstances perhaps it is better to allow more transparency and allow cases to be covered by experienced and responsible reporters, rather than leave the mainstream media to follow the blanket suppressions while social media flagrantly disregards them.

The current arrangements fuel ignorance and resentment towards the legal system rather than the respect and understanding that transparency should bring.

And if the concern in the Pell case was to ensure he wasn’t the victim of mob mentality in the vein of Lindy Chamberlain (or John Proctor) then that battle was lost long ago. Again, for all the challenges of crowd behaviour in public controversies, transparency is usually the best antidote.