ON the eve of the 1983 election, Bob Hawke made the craziest election commitment of all: the pledge not to break a promise.

He told a willing crowd at his campaign launch: “I believe the Australian people have had enough of election promises made only to be broken.”

He went on to assure voters that he would maintain controls on mortgage interest rates, continue assistance for the footwear, clothing and textile industries, fund a separate ABC rural network, construct the National Museum, introduce a national Bill of Rights and fixed four-year terms and wipe out (yes, wipe out) the tax evasion and avoidance industry.

Which goes to prove that a tally of promises kept and those supposedly broken is a hopeless measure of a government’s worth.

There was barely a hint in Hawke’s campaign speech of the reforms by which he came to be judged as one of Australia’s most successful prime ministers. The Hawke government’s fiscal conservatism did not emerge until his first budget, and even then its significance was lost on all but a few.

For Tony Abbott the gotcha game begins at 7.30 tonight when the nitpickers comb through his government’s first budget.

He should prepare for a torrid week, for the expert class has not afforded him the latitude prime ministers customarily enjoy in their early days in government.

There is a justifiable apprehension in Coalition ranks about how tonight’s budget will be received and the damage to the Liberal Party brand in NSW has not helped to steady the nerves.

One wag suggested NSW Premier Mike Baird could best deal with the problem by adding ICAC to the dangerous dog register. Say what you like about rottweilers, but at least they possess a rudimentary sense of natural justice.

Moments like this call for the advice from older and wiser heads, and former Howard government minister David Kemp’s Alfred Deakin lecture last week on the nature of good government was particularly well timed.

Kemp took issue with the current political orthodoxy that “good government is simply doing after the election what the party promised before … almost regardless of what it has a mandate to do.”

He is troubled too by the modern notion that the task of a government is to balance the demands of special interests. The story of Labor provides a cautionary tale in the fate of a party that fails to resolve the tension between the noisy demands of a few and the interests of the many.

Kemp urged his party to look to the example of Robert Menzies, for whom “the capacity of a political party to rise above the crush of special interests was fundamental to good government.”

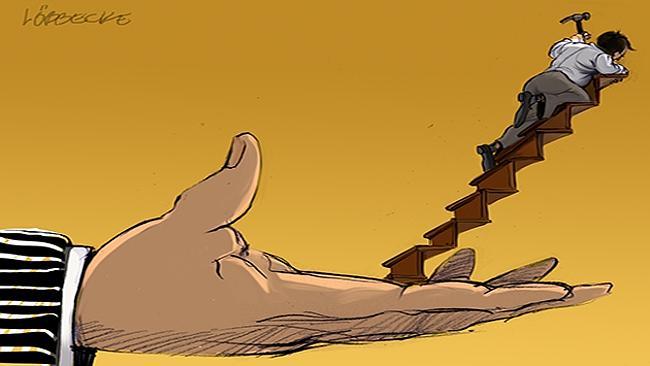

Menzies’s measure of good government was the extent to which it served the broad public interest, which the tried and tested philosophy of liberalism means allowing ordinary citizens to pursue self-interest

People’s natural desire “to achieve better lives for themselves and their children, to make their own ways of life … freedom that encourages people to plan and save to realise their dreams” was “the driving force of improvement in the world,” Kemp said, not government central planning.

“It is the role of government to tend and foster these qualities, to respect the citizens, and persuade them with reasoned argument, to represent their best side and be their agents in putting in place the policies that will preserve their democratic rights and their capacity to realise their potential.”

The notion of trusting individuals to make a good account of themselves without a leg-up from government or heavy-handed regulations is alien to modern progressive thinking.

Anthony Albanese told Insiders after last year’s election that history would judge the Gillard government kindly, boasting “we got through almost 600 pieces of legislation”.

The dogma of the New Left insists that the answer to every economic and social ill is assertive government.

The Right, however, appears to have become fixated on a metric of its own; that a government’s worth is determined by a single measure; government spending as a proportion of GDP.

Economic dries are genuinely shocked at the prospect of a debt levy for high-income earners, regarding it as a fundamental breach of faith. The Abbott government is squibbing it by increasing revenue when there are plenty of dumb spending programs that can be axed.

They are right of course on one level; government spending is out of control and the bloated public sector is an unproductive drag on the economy. Yet reducing government spending is not an aim in itself, since the illiberalism that crushes private incentive is not purely economic.

The most objectionable consequence of open-ended welfare is not that it depletes the budget but that it drains the national stocks of ambition, initiative and enterprise.

The business of life becomes foundationless as we head towards the dystopia Menzies once predicted, populated by state-supported boneless wonders. “Leaners grow flabby; lifters grow muscles,” Menzies said in his 1942 Forgotten People radio talk. “Men without ambition readily become slaves.”

The purpose of deregulation, the reform of higher education, free trade initiatives, removing the incentive to join the ranks of disabled pensioners, raising the retirement age and many other Coalition reforms should not be merely balancing the books.

Their success must be measured by their capacity to help Australians to make the best of their lives. Forget the Left; the centre Right too needs a refresher course in the principles of liberalism that have built the prosperity of Australia for 200 years. There is no mathematical formula by which to judge an administration. Good policy will inevitably reduce the size of the public sector, but prudence demands more than a hairy-chested obsession with spending cuts.

Make no mistake, Joe Hockey’s budget today must include a credible plan for a swift return to surplus, but for the heirs of liberalism, that is not the only test.

As Kemp told the party last week: “Good government must be based on the acknowledgment that it is individuals who matter.”