An Asian marvel we ought to know better, not least because it's got Seoul

AUSTRALIANS may be forgiven for knowing next to nothing about North Korea. It takes a deal of effort to get in there and few North Koreans can be encountered in Australia.

That is, unless you happened to be walking your dog along a beach near Lorne on Victoria's Great Ocean Road one night 10 years ago, when you would have stumbled across a botched landing from a North Korean freighter involving a large quantity of heroin. But any resulting chat was unlikely to have included building Australia's role in the Asian Century.

Australia's official imports from North Korea last year reached a minuscule $8 million, most comprising oil products and, intriguingly, office machines. Zero exports were recorded. South Korea, however, is a different matter. It is our third biggest export market, buying $20 billion of our products last year: chiefly iron ore and coal for steelmaking, oil and beef. Our largest single customer anywhere is South Korean steelmaker POSCO.

About 100,000 Koreans live permanently in Australia and, temporarily, more than 20,000 students - the third highest student group after China and India. Next to young Britons, young Koreans take the most working holiday visas here. This year is the 60th anniversary of the end of the Korean War, in which 17,000 Australians fought and 339 died.

South Korea, like Australia, views itself as a middle power in our region, although its population at 50 million is about twice ours. It is a US ally, a lively democracy, with open media and courts that mostly operate fairly.

So why do so few Australians know anything about the country? Perhaps because we visit so rarely, despite its pop culture and arts, so eagerly sought elsewhere in Asia, and despite its extraordinarily beautiful countryside - with Seoul surely the only capital on the continent that is built on and around tree-clad mountains, now in their autumnal reds and golds.

Last year's Asia white paper at first removed Korean as a proposed priority language for young Australians, although it was reinstated some months later.

Here, then, in the interests of helping bridge the river of ignorance dividing two countries that should be friendlier, are some things about South Korea that you may not know:

Most young South Koreans have little interest in North Korea and pay it scant attention - even though Seoul is within artillery reach of the border.

Ross Gregory, a successful and entrepreneurial Australian in Seoul, a fluent Korean speaker, a senior finance executive and investor in restaurants and gyms, says 20 years ago Koreans might have spoken in casual conversations once a week or even once a day about the north: "They were genuinely sad about the situation."

But now it may come up as rarely as once a year. Young South Koreans won't have a bar of the notion of unification; they would have to bear a huge cost burden, and their personal interests are enlisted elsewhere in the world.

Despite the country's continuing economic success, Koreans are reluctant to have children, in part because of the high cost of housing and education.

A Korean friend of a friend spends $10,000 a month on after-school coaching for his two children, but although he has a high-powered job this is stretching his salary perilously. Some Koreans return home in their 30s, perhaps after a marriage has failed. They are called "kangaroos": returning to the pouch. Unlike other north Asian countries, South Korea allows some immigration, chiefly of young wives for older farmers who cannot find Korean women willing to share the agrarian lifestyle. More than half come from China and Vietnam.

One of the most popular figures on television is 36-year-old Sam Hammington, a New Zealand-born Australian and a Swinburne University graduate who first came to South Korea as an exchange student 15 years ago and picked up a remarkable capacity to speak humorously in Korean. A full figure, he goofs around and plays for laughs, chiefly on the show Real Men. He and his Korean bride wore the outfits of an emperor and empress at their wedding a fortnight ago.

South Koreans form the biggest group of expatriates in China. Big cities such as Beijing and Shanghai have whole Korean suburbs, chiefly comprising managers and technical staff working in the vast manufacturing operations run by Korea's big brand names, including Samsung, Hyundai, LG and Kia. South Korea may have recently overtaken Taiwan as the biggest investor in China.

Anti-Japanese feelings have strengthened in recent years in South Korea, despite the many obvious affinities between the close neighbours. It was Japan, stepping in to rule Korea for more than 40 years, that brought to an end the five centuries of the Joseon dynasty at the start of the 20th century. Recently Koreans celebrated with nationalist, anti-Japanese fervour Dokdo Day, named in honour of two islets and 35 smaller rocks also claimed by Japan, which calls them Takeshima. South Korea has built a helipad, lighthouse, police barracks, desalination plant and mobile phone towers on the 0.19sq km of land and recently staged a fashion show on the rocks.

The country's first female leader is President Park Geun-hye, who grew up in the Blue House, the presidential residence, because her father, Park Chung-hee, led South Korea from 1963 to 1979 and is widely credited with the nation's extraordinary industrialisation. After the Korean War, UN development experts advised the agrarian country to learn from Kenya. Park Chung-hee instead turned it towards manufacturing. Today the average Korean is 23 times better off than the average Kenyan. Park Geun-hye's mother was assassinated by a Japanese-born North Korean in the National Theatre in 1974. It is said that when Park Chung-hee learned his wife had succumbed to her injuries, he was making a speech; he acknowledged the news but kept talking.

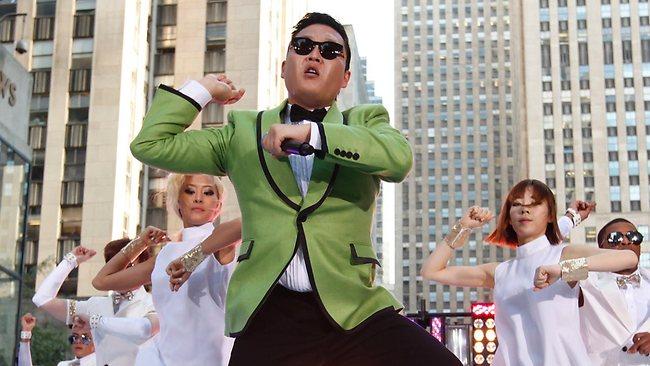

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon is a South Korean, as is World Bank president Jim Yong Kim. But more famous by far is Park Jae-sang, the performer known by his stage name Psy, whose Gangnam Style is the most watched video of all time. Gangnam is a busy, modern office district in Seoul, its apartments affordable only to the very rich.

The best known Australian business figure in South Korea is John Walker, who introduced Macquarie Bank there in 2000 and is a regular on international roadshows spruiking the country. He has led the bank into a remarkably profitable role and chairs the Australia Korea Business Council. Walker is also the author of an acclaimed series of illustrated children's books with Korean themes, published in English and Korean, that reflect his love of the country's mountains and wildlife.

To help keep up the pace, South Korea is halfway through building at Incheon, west of Seoul, a "free economic zone" that covers an area three times the size of Manhattan, to include what it claims will be the biggest port in the region, as well as one of the world's busiest airports. South Korea is at the geographical centre of a region that produces one-third of global gross domestic product.

Its own famous brands, and companies such as Cisco and GE, which are establishing research centres there, are pioneering products that include: a fridge with a camera inside that can show on your smartphone what's left and what you need to buy; apartments with a concierge system built into your smart TV through which you can talk to someone at a remote centre who will arrange to supply your needs; and a table top that charges, and connects to WiFi, electronic gadgets such as phones or tablets that are placed on it.

Korea used to be known as the Hermit Kingdom. It's hardly that today. It's the ultimate wired world.

Rowan Callick visited South Korea as a guest of the Korean Trade-Investment Promotion Agency.