In anybody’s language, the sodden images of the damage wrought by Cyclone Gabrielle, from coastal Auckland down through Hamilton and the region of Gisborne, told their own story.

The apparently new style of reporting, in which Maori words and phrases are liberally peppered in the standard English, might have been a little more puzzling.

Suddenly, or so it seems, the language of New Zealand’s original inhabitants is everywhere — and not just in the news media.

Quite a number of New Zealanders, including some of the 890,000 who identify as Maori, sometimes admit to being a little baffled, too.

Maori is only spoken fluently by around one per cent of the country’s overall population of 5.1 million. But now, increasingly, it’s enjoying a popular billing like never before, with even the names of cities getting a fresh coat of linguistic paint.

Just ask Gabrielle. Auckland, the first of the cities she blew into, now gets namechecked more often as Tamaki Makaurau.

Regional Gisborne, also the site of considerable damage, is Tairawhiti. And Hamilton is Kirikiriroa, thanks.

The same holds for references to New Zealand itself, which is as likely to pop up as the undeniably pretty-sounding Aotearoa as the other one used by the rest of the world since 1840.

Maori has been one of Aotearoa’s two official languages since 1987. But much of the current ramping-up has happened on the watch of the finger-wagging Labour government over the three years New Zealand was effectively shut off from the rest of the world during Covid.

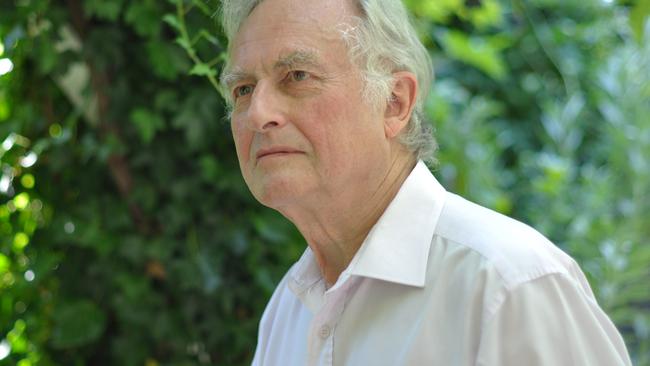

So what happened? As the British evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins discovered when he was here last week, grasping the official answer to that requires a little work “because every third word of the relevant documents is in Maori”.

Not to mention the host of government departments to have had a splash of fresh linguistic paint on their names: Waka Kotahi for what was the NZ Transport Authority, Te Tari Ture o te Karauna for the Crown law Office, Te Tari Arotake Matauranga for the Education Review Office, and so on.

And woe betide any public servant who’s not fully on board. Almost 40 years ago, a heroic government toll operator, Naida Glavish, almost got fired for having the temerity to insist on using the familiar Maori greeting of “kia ora”. These days she might find herself in similarly hot water for offering a hearty “good morning”.

For some, of course, the changing times are no more than a long-overdue mark of respect to the first inhabitants of these shaky Polynesian isles, no more controversial than the aboriginal invocations one might often hear in many Australian settings. What good is an official language, after all, if people aren’t using it?

Yet other nations have many languages within their folds, and people somehow seem to be able to converse in one or the other without creating a new pidgin along the way? Other countries simply require kids to learn the other language as a separate vernacular at school. For some reason, this isn’t a starter in New Zealand, where the burden of instruction falls instead on reporters and bureaucrats who more often than not are themselves not fluent in the language.

Might it be, as Dawkins put it in a bemused article in the UK Spectator after his NZ tour: “Self-righteous virtue-signalling, bending a knee to that modish version of Original Sin which is white guilt”?

Others have more practical concerns. In the field of mental health, for example, hundreds of new Maori words have been coined for academic use.

What used to be known as autism, for example, now appears as takiwatanga, which means to have “one’s own sense of time and space”. But how this blast of folksiness fits with the diagnostic criteria for the debilitating spectrum of disorders affecting communication and behaviour is really anybody’s guess.

Even globally recognised trademarks, which are almost only ever transliterated as they migrate across language groups, have undergone a similar transformation. Among the latest: Pukamata instead of Facebook, if you please.

Most striking of all, perhaps, is the fact that the institutions most zealously promoting the new style are themselves sorely lacking for Maori faces at their helms.

Other than a smattering of boutique agencies, usually those dedicated mainly to indigenous affairs, none of the larger government ministries in New Zealand is headed by a Maori.

The same is true of the roll of all-caucasian vice chancellors at the country’s eight publicly funded universities. And none of the major mainstream media outlets in New Zealand has ever had a Maori running the show.

Not to mention the resolutely all-white retinue of Labour leaders since the party of equality’s inception in 1916.

Shane Jones, a one time Labour Maori MP, says a lot of the current activity seems like a waste of effort while larger social and economic concerns for Maori, remain unaddressed.

Jones, who is fluent in both lingos, has called on government ministers to focus instead on “the development of our people and less daubing every new report or project, that never gets delivered anyway, with a yet more romantic Maori name.”

Many Kiwis — a Maori word, by the way — would likely agree.

David Cohen is a Wellington-based journalist and author

Australians who followed the media reports of the recent ghastly weather in New Zealand might have been struck by a gale of apparently new words amid the billowing meteorology.