Karl Lagerfeld: legend’s life of frills and spills

Karl Lagerfeld was known as much for his eccentricity as for his designs.

In 1983, more than a decade after the death of Coco Chanel, Karl Lagerfeld took over her fashion house, making it bigger, brasher and brighter.

In the process he transformed the business into one of the world’s most profitable luxury labels.

To rescue a former superbrand that had been surviving on perfume sales alone was a monumental task. Yet attempting to emulate the legendary Coco would have been suicidal: this was a woman whose creations had been worn by Jackie Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe, Marlene Dietrich and Lauren Bacall. Instead, Lagerfeld took its core elements — the tweed jackets, the pearls, the quilted bags — and manipulated them into a more modern, raw and fresh product.

As he said: “My job is to reinvent Chanel, so I have to play with the codes, kill them even, before I can use them again.”

He may have shocked the purists but soon Chanel regained its status. With bolder colours, shorter hemlines, sexier tailoring and accessories with a playful hint of the kitsch, it gradually morphed from its staid, post-Coco state into something vibrant and youthful.

Yet the early days of the Lagerfeld-Chanel partnership could be stormy, with the designer pointedly refusing to take the customary applause at the end of the 1985 winter shows. “When people behave well I conduct myself well,” was his icy riposte to those rash enough to ask about the reason.

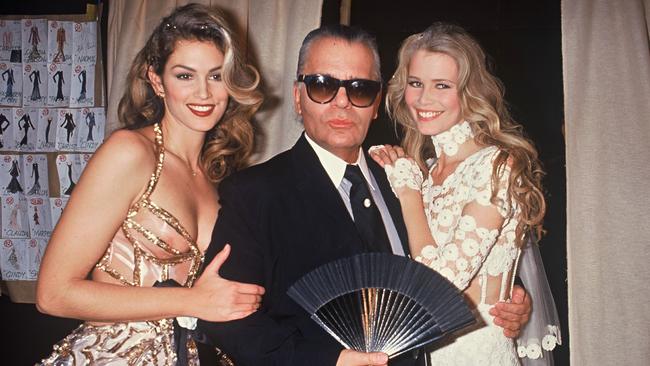

While he liked to play the part of the dilettante or the dandy, Lagerfeld was one of the fashion industry’s great eccentrics. Nowhere was that more apparent than in his uniform of dark sunglasses, crisply starched white shirts with 10cm stiff collars sitting snugly under his chin, black trousers, belt buckles encrusted with diamonds, fingerless biker gloves, chunky rings adorning every finger and his famous fan, a fluttering emblem of high camp. The trademark ponytail was treated with a white powder shampoo each morning. “I am like a caricature of myself, and I like that,” he said enigmatically. “It is like a mask. And for me the Carnival of Venice lasts all year long.”

Lagerfeld was also highly volatile and at times terrifyingly autocratic, which earned him the nickname “Kaiser Karl”.

In 2004 he was furious to discover that the clothing chain H&M had sold his designs in a UK size 16 after he collaborated with the company to produce an affordable range of clothing. “What I really didn’t like was that certain fashion sizes were made bigger,” he raged. “What I created was fashion for slim, slender people.”

For someone well-versed in weight changes of his own, such revulsion was surprising, as was this turn in direction for a man known for creating only luxury products. Yet this was Lagerfeld, a designer with remarkable intuition who lived by his own rules. “For a long time I have seen the girls in my Paris studio wearing H&M, mixing it with Chanel and other labels,” he said. “There is no in-between any more. I believe in extremes — Chanel and H&M, very expensive and very cheap.”

Despite the controversy, Lagerfeld’s H&M line sold out in minutes, sparking a string of similar designer-high street collaborations. He had spotted a trend, cultivated it and watched while everyone else followed.

Lagerfeld was also his own photographer, shooting many of the campaigns for the press kits and catalogues of Chanel, Fendi and his own Lagerfeld Gallery. His work appeared in glossy magazines around the world and in the fine-art exhibitions of European galleries. He also published his own books, opened a bookstore in Paris and in 2006 released a two-disc CD called Karl Lagerfeld: My Favourite Songs, which included an eclectic range of music from his mixtape. It featured artists such as Devendra Banhart, rock bands such as Siouxsie and the Banshees as well as classical composers such as Stravinsky.

At the same time there was seemingly no end to his ability to create controversy. Anna Wintour walked out of a show in 1993 when he employed strippers to model his Fendi collection, and there was uproar when he used a verse from the Koran in his 1994 spring collection for Chanel.

He engaged in a running battle with animal-rights campaigners over his use of fur and in 2012 he described the singer Adele as “a little too fat”; he also insulted Pippa Middleton, the sister of the Duchess of Cambridge, by saying he did not like her face and “she should only show her back”.

Karl Lagerfeld was born in Hamburg, northern Germany, the son of Otto Lagerfeldt and his wife Elisabeth (nee Bahlmann). His father was an elderly businessman who made his fortune exporting condensed milk, and who Karl sometimes claimed was Swedish. His mother was a lingerie saleswoman from Berlin and an accomplished violinist. His parents were cultured people whose idea of small talk at dinner was debating the religious philosophy of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.

There was some confusion about Karl’s year of birth, which he claimed to have been 1935 or 1938. Official sources, including his cousin Kurt, a school friend, and the baptismal register in Hamburg state it was 1933. He had an elder sister, Christel, and a half-sister, Thea, from his father’s first marriage. Both were sent away to school, making him effectively an only child.

From an early age Karl knew what he wanted. “As a child I wanted Austrian lederhosen,” he said. “I always wanted to be different from other people. I hated children. I was born with a pad of paper in my hand. I was looking at images before I could read.”

He was brought up in a mansion, had his own valet from the age of four and was educated at a prestigious private school. Despite living through World War II, when the family moved to an isolated country estate in northern Germany, he was deprived of nothing. “When I was a child my parents gave me six bicycles,” he boasted. “But I wouldn’t share. No, no, no.”

Lagerfeld’s relationship with the mother he adored was well-documented, not least because he revelled in describing her stern and unforgiving behaviour.

“My aunt told me my mother’s ambition in life was to be mean to me and to have fun,” he wrote.

She gave him little praise, tore up his diaries, banned him from attending his father’s funeral and her own, and dismissed his stammering at the age of six, telling him: “You may be a child, but I am not.”

He retained a steadfast admiration for her despite her severity. “She was right to be critical,” he said. “I needed it. I always knew I was loved.”

His awe verged on the obsessive: he wore her wedding rings around his neck, another of her rings on his finger and slept in his childhood bed.

In Hamburg after the war, Lagerfeld, then in his early teens, attended his first fashion shows, featuring designs by Christian Dior and Jacques Fath. “I loved it — the mood, what it projected, the idea of a life,” he told the British newspaper The Observer in 2007, adding that until then he had felt he had been born too late. “I had missed all this fabulous life before the war, the ocean liners, the Orient Express.”

He left home at the age of 14, unsupported by his father, and changed his name to Lagerfeld without the “t”. He finished his secondary education at the Lycee Montaigne in Paris, where he excelled in drawing and history. In 1954 his design for a woollen coat, with a high neckline and a plunging V-shaped opening in the back, won a prize from the Secretariat International de la laine, an honour he shared with Yves Saint Laurent, who had designed a dress for the event. Pierre Balmain, one of the judges, with his own fashion house, offered Lagerfeld the post of junior assistant.

After six months the young German was apprenticed to Balmain, but in 1958 he left “because I wasn’t born to be an assistant” and joined the couturier Jean Patou. That experience was “a bit slow” and after three years he went freelance. As pret-a-porter took hold in western Europe in the 1960s, Lagerfeld found his feet, designing for the Rome-based furrier Fendi and the fashion house Curiel.

Yet it was at Chloe, the French fashion house, that Lagerfeld sealed his reputation, initiating the vogue for perfumes with an eponymous scent in 1975. This, teamed with his coveted designs, notably the elegant beaded and bias cut gowns with a focus on femininity that still underpins Chloe today, ensured that profits were high.

At much the same time Lagerfeld had shared a relationship with Jacques de Bascher, a wild French aristocrat, but it led in 1974 to an irretrievable falling out with Saint Laurent, who shared de Bascher’s affections. De Bascher died from an AIDS-related illness in 1989 and is buried alongside Lagerfeld’s mother in the private chapel at the house in Brittany that he inherited from her. In the 90s he bought a home in his native Hamburg and renamed it Villa Jako in honour of de Bascher, but claimed he could not live in Germany because of “the lack of humour”. He returned to the city in December 2017 for a triumphant homecoming, using the new €789 million Elbphilharmonie concert hall for a Chanel show.

After Bascher’s death his closest companion was Choupette, a red point birman cat who had thousands of followers on social media. He allegedly once said he would marry Choupette if it were legal. Lagerfeld also called his favourite models his “Choupettes”.

By 1983 Lagerfeld was seeking new challenges and found one in Chanel, which had been left in a vacuum following the death of Coco in 1971.

Testament to Lagerfeld’s power in the industry was his durability. Despite leaving Chloe in 1983, he was asked to return in 1992. It was a short-lived affair, however, due in part to his ever expanding portfolio. No longer just a designer, he also had a fervent interest in photography, literature and illustration; he created costumes for La Scala opera house in Milan and the ballet in Monte Carlo. When his contract at Chloe was not renewed in 1996, Stella McCartney was hired as his replacement, prompting Lagerfeld’s unabashedly caustic response: “They should have taken a big name. They did, but in music, not fashion.”

For 30 years Lagerfeld’s main residence — he had at least five homes — was on the rue de l’Universite in the 7th arrondissement, an 1672sq m mansion built in the 1700s with a grand curving marble staircase. In 2007 he sold it and bought four apartments on two floors of a 200-year-old building on the Quai Voltaire, on the Left Bank overlooking the Louvre. The lower floor was devoted to the old world, featuring a library furnished with pieces from the 18th and 19th centuries as well as from his art deco collection. The upper floor was for art and furniture made after 2000.

Lagerfeld’s day was marked by a strict regime: he slept wearing a long white nightdress in a bedroom with no curtains on a four-poster bed on which the posts were made from fluorescent bulbs; daylight and hunger were his alarm clocks; meal times were scheduled for exactly 8am, 1pm and 8pm. He drank only Coca-Cola Zero, delivered on a lacquer tray, and never touched tobacco or drugs. Yet he was notorious for keeping dinner guests waiting, sometimes for up to three hours.

While dropping off to sleep at night he would read European literature of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, usually in its original language. “He does not do anything as banal as translated books,” observed Geordie Greig in Tatler in 2007, adding Lagerfeld had a library of 150,000 books, adored the poetry of Emily Dickinson and could explain the point of an architect such as Peter Behrens, who was mentor to Gropius and Le Corbusier.

Some people reported that when reading paperbacks, Lagerfeld would tear out the pages as he finished them, while others said he spoke at such speed that his sentences sounded like one long and incomprehensible word.

There was rarely any respite or down time for Lagerfeld, who was said to get nervous even at the thought of a holiday. “What I like best in the world is the job,” he said in 1986. “Yes, I am busy, but I don’t think it is busy in the sense of boring work. Work is when you are bored and don’t like what you do. I don’t know when work starts and when work stops.” On another occasion he declared that retirement was not an option: “Why should I stop working? If I do, I’ll die and it’ll be all finished.”

The Times