Townsville ‘vigilantes’ accused of stirring racial tensions

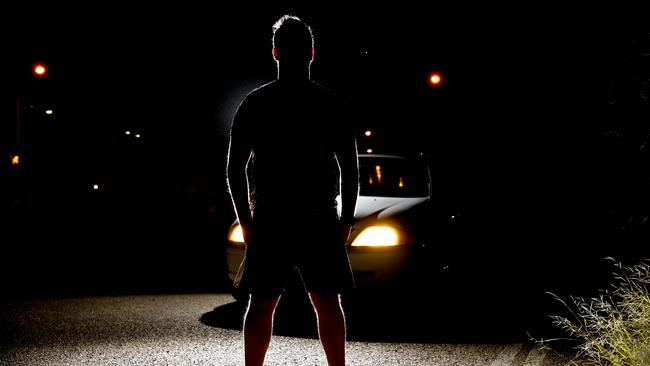

By day, he’s a house painter, quiet and unassuming. By night, Kenneth drives the streets of Townsville looking for trouble.

By day, he’s a house painter, quiet and unassuming, a young man who speaks softly and keeps a baseball bat in the boot of his car.

By night, Kenneth drives the streets of Townsville looking for trouble. It’s all too easy to find in a city besieged by a wave of youth crime.

The police are doing their best, but 20-year-old Kenneth and his mates from Townsville Against Crime have taken it upon themselves to become the “eyes and ears” of the law, patrolling from midnight to near dawn for house breakers and joyriders.

They say they are doing no more than their civic duty — a suspicious sighting is immediately called in to the police, Kenneth insists — and if something kicks off they have the right to defend themselves, like anyone else.

“We’re not into that vigilante shit, and the cops know that,” he says. “If I see someone breaking into a house I get on to the cops and if there’s people home I will try to warn them. You don’t go in, because that can turn out to be a hostage situation and no one wants that.

“You sit outside, hitting the horn or whatever to make noise, and that’s usually enough. If the crims start running you try to grab them and perform a citizen’s arrest until the police come. I’ve done that a few times.”

Others say that Kenneth’s group and those like it networked through Facebook are anything but a mobile neighbourhood watch.

“I make no bones about this … they are vigilantes and they’re probably even more dangerous than the kids they chase,” complains veteran indigenous activist Gracelyn Smallwood. “My greatest worry is that kids of all colour are being targeted.”

It doesn’t help that the offenders are overwhelmingly indigenous and that Kenneth and his compatriots are mainly white. Townsville has a history of racial unease and the depredations of a small but hardened core of troublesome young people, numbering no more than 30, according to senior police, has brought long-simmering tensions to the surface.

The problems began two years ago at a time when nearly 900 people had been thrown out of work by the collapse of Clive Palmer’s nickel plant at Yabulu, north of the city. Youth unemployment soared to 21 per cent. A community that took pride in its sunny optimism was deeply shaken as car theft doubled and burglaries spiked in what turned out to be a new form of niche crime: kids broke into homes to grab the keys to cars that were then taken for joyrides, frequently in appallingly dangerous circumstances.

This is intensely personal business for Kenneth. After being confronted at home by five intruders, who were chased away, he found himself deeply angered by stories that women living alone were being singled out as easy marks.

“I thought, at least I can defend myself, but they can’t. I decided to do something about it and I guess that’s part of the reason I’m here,” he tells The Weekend Australian.

Kenneth is cruising the backstreets of Vincent, a hardscrabble suburb, on the lookout for stolen cars. A handheld police scanner is crackling as his phone pings with messages. His is one of six patrol groups that are active and they pool information on what’s hot in the north Queensland city. He says Townsville Against Crime has 2000 online members, of whom about 20 participate in the beat work.

Earlier in the day, a stolen Kia hatchback was videoed tearing through the area and the footage has been shared with Kenneth. Whoever took it was rumbled. One of the joyriders, a T-shirted boy, pulled himself out of the passenger seat and hurled a bottle at the car tailing them, hanging precariously from the open car window. Kenneth’s first call of the night was to report that the Kia had been crashed in nearby Heatley and abandoned.

Now he’s watching for a black Mercedes-Benz C-class that’s been spotted speeding crazily on Riverway Drive.

“I think that’s it,” he says. The powerful sedan turns a corner, accelerates and disappears into the night. The smell of scorched rubber reaches into our car. “Yep, definitely stolen,” Kenneth says.

Perhaps for our benefit, he makes no attempt to chase.

We meet up with Anthony, a 38-year-old father of seven who runs Annandale Night and Day Watch, another community patrol. A burly man who works in hospitality, he admits that some groups are aggressive.

“They will force anyone off the road to go after stolen cars,’’ he says. “They make it worse for everyone … we don’t have anything to do with them.”

Anthony says he will take on offenders, though it’s not his preference.

“I’m not trying to catch these kids to flog them,” he explains. “If you do that, you’re the one who ends up in court. So you sit back a bit. But if they come at me — and sometimes they do that — I will defend myself, like anybody else.”

Both young men asked that their surnames not be published for fear they could be targeted for retribution.

Kenneth says police cars have been rammed by stolen vehicles with young offenders at the wheel, a point confirmed by district police boss Kev Guteridge.

The chief superintendent welcomes the help of the patrol groups, “a model we are seeing morphing out of neighbourhood watch”. He calls them “genuine people who are concerned about crime in this city”.

“There is no evidence before me of … these people taking the law into their own hands or acting unlawfully,” Guteridge says, rejecting the claims of vigilante action. “They are the extra eyes and ears the police need to get on top of this. When something is going on, they ring the police … they are not dealing with things themselves.”

Harrison Bell, 18, says that isn’t his experience. The city of 190,000 is big enough to offer a wealth of opportunity for kids to thieve, yet small enough for people to know who’s up to what. Bell isn’t indigenous, underlining the folly of stereotypes. Before getting his life together to train as a stockman, he cycled in and out of juvenile detention, 12 times between the ages of 12 and 17, convicted of car theft, assault, stealing and burglary. “I was in with a real bad crowd,” he says.

So he took seriously a warning that he was on a vigilante “hit list”, to watch his back. “When I used to live in Vincent you would see these big four-wheel-drives flying around, chasing kids,” he continues. “From what I could see, the police turned a blind eye.”

Guteridge denies this, insistent that “vigilante action cannot and will not be tolerated”.

Smallwood says she has been pilloried for speaking out about the demonising of young indigenous people when a small minority was responsible for nearly all the thieving. She doesn’t for a moment condone this: as she points out, her house has been broken into, too, and her brother had his cherished Ford Fairlane stolen and torched. “We’re all part of this community, we’re all being affected,” she says.

While argument rages over exactly what caused youth crime to surge in Townsville — Smallwood believes that alcohol-management plans in remote indigenous communities have enticed heavy drinkers to move to the city with their children, while Guteridge cites “intergenerational dysfunction among some families” — the nuances are lost on the victims, fed up with the constant threat.

Samantha Kingsley, 50, is grateful that Kenneth now keeps an eye on her snack bar in Heatley after enduring seven break-ins in the past 12 months. To add insult to injury, she knows the boys responsible for a number of the forced entries, brothers aged 16, 11 and 7, who were caught in the act on security cameras. Kingsley and her husband, Max, would give them hot chips when they turned up hungry and broke.

After she barred them, their father stormed into the shop, incensed. As he tells it: “The lady … took it out on the kids. She called them little turds. They didn’t hurt anyone.”

Kingsley shakes her head and sighs. “You can’t win,” she says.