Watchdog a law unto itself

VICTORIA'S Office of Police Integrity seems to have stepped well over the mark in investigating senior police.

PHILIP Priest QC, a leading criminal barrister renowned for his radar in detecting lying police and shonky investigations, had spent months with his legal team examining the prosecution evidence. It was a weighty brief comprising the product of hours of secret intercepts of telephone conversations, surveillance in Melbourne by covert operatives, highly protected operational briefings, and transcripts of interviews of senior police, investigators and support staff.

In all of the hundreds of pages of material there was a common denominator: Victoria's controversial Office of Police Integrity, the architect of Operation Diana, as it targeted the then assistant commissioner Noel Ashby, his mate, the then police media chief Stephen Linnell, and Ashby's industrial ally, the Police Association's then secretary, Paul Mullett.

In late June 2009, Priest summarised the case on behalf of his client, Ashby, and wrote a scathing confidential memo in which he cited the OPI for conduct he believed amounted to perverting the course of justice.

"It is clear that the OPI's conduct in the investigation of Mr Ashby has been reprehensible," Priest wrote in the memo obtained by The Australian. "[The] practices of the OPI in their handling of witnesses, and the moulding of witnesses' evidence, have been revealed by cross examination.

"The behaviour of the OPI both with respect to the methods used generally in this matter and specifically with respect to discovery has wide ramifications for all serving police no matter their rank.

"The OPI hid documents from the defence. Such documents as we were able to flush out were heavily edited. The reasons became clear. There is much for the OPI to hide.

"Again, if the OPI is a law unto itself with respect to an assistant commissioner, it is reasonable to assume that it will be a law unto itself with respect to all ranks.

"The reason why there is a refusal to call [a named OPI investigator] is obvious: there is a sig

nificant unwillingness to subject OPI investigative practices to scrutiny."

Eighteen months earlier, the OPI had staged a series of public hearings in which numerous telephone conversations were played. The embarrassment of Ashby, Linnell, Mullett and others was acute.

Their careers were ruined during the public hearings as their chit-chat and sledging of professional colleagues and enemies filled the OPI hearing room. Audio files were given to media organisations and the sound bites became fodder for weeks on morning radio.

For the most part, their conversations amounted to office gossip and political manoeuvring to advance career prospects. But there was an extremely serious assertion made by the OPI, that a then-serving police officer and union delegate, Peter Lalor, had been tipped off in August 2007 by a union contact, via Linnell-to-Ashby-to-Mullett, that Lalor was the target in another police operation, Briars, which was investigating alleged police links to a murder.

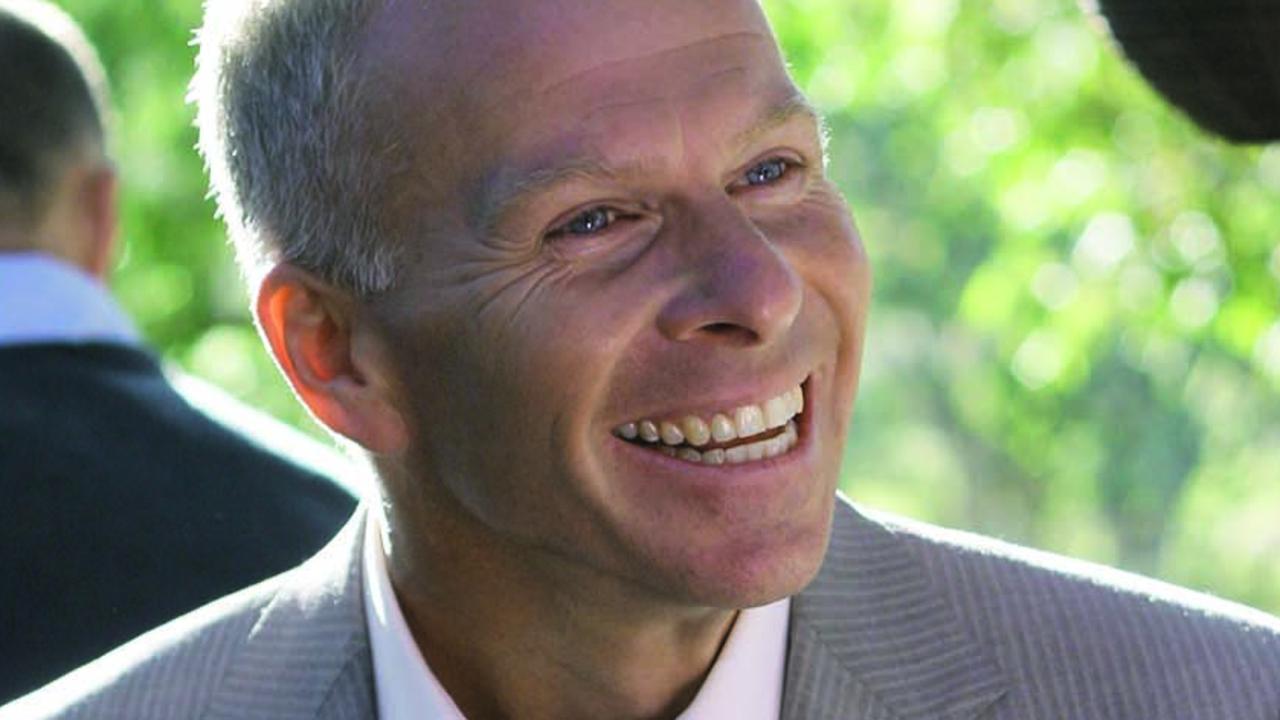

Ashby was a familiar face to Victorians. He was a dedicated career officer who had vast operational and policy experience.

He had solved murders and brutal rapes when he worked in crime, and he had developed planning and strategy as a key part of the hierarchy.

He was a networker, a polished media performer in his role as assistant commissioner with responsibility for traffic, and politically savvy. He believed he was a strong chance to be the next chief commissioner.

After the OPI's public hearings in November 2007, Ashby was disgraced, lampooned, unemployed and facing a stretch in prison.

As the transcripts of their telephone conversations show, Linnell and Ashby spoke often and candidly, and Ashby and Mullett spoke often too. But were they corrupt criminals, or frantic gossips?

Would Mullett, one of Victoria's most highly regarded detectives and noted crim-catcher, before he became an industrial advocate, have warned Lalor?

The claims that Lalor had been tipped off, that he was a target in Operation Briars, were strenuously denied. There was scant, if any, evidence that Mullett was even told by Ashby of the alleged murder connection; or that Lalor had learned of Operation Briars from the union or Mullett.

And after the smoke had cleared with the fanfare after the public hearings run by the OPI, the Director of Public Prosecutions did not attempt to prosecute over the murder tip-off claim, leaving Ashby and Mullett facing perjury charges over their testimony to the OPI.

Like former police commissioner Christine Nixon's recollections during her recent testimony to the bushfires royal commission, they had left information out. Linnell pleaded guilty and walked away.

But the more that Priest, deputy chairman of the Victorian Bar Association's ethics committee, examined the evidence against his client, Ashby, the more convinced Priest became that it was the OPI that needed scrutiny.

He zeroed in on chunks of evidence that depicted the OPI's conduct in its covert investigation and its subsequent public hearings that had destroyed the careers of Ashby and Mullett, a powerful political figure as secretary of the Police Association and a relentless industrial advocate on behalf of about 11,000 sworn police officers in Victoria.

Priest's scathing memo summarises prima facie evidence which he believes the OPI misused powers as it "trampled on the rights of an assistant commissioner".

If the OPI acted this brazenly and unlawfully while investigating a top officer, Priest surmised, "one is left to wonder how the ordinary rank and file will be treated".

Priest smelled a rat in the modus operandi of the OPI which, he believed, had failed its own integrity test, may have acted illegally and perverted the course of justice. For legal reasons, several of Priest's criticisms cannot be published here. But the Police Association has now asked him to investigate further. Mullett and Ashby are in no doubt that the OPI's motive from the start was to oust the two men. Priest has been asked to advise on remedies for damages for Mullett, who was acquitted of the remaining two charges when the DPP withdrew its case last June, and for Ashby, who beat the case three months ago when it was found that all of the OPI's evidence was useless because the OPI had not properly sworn its delegate, Murray Wilcox QC. The OPI has removed from its website every reference to the case, which became its biggest embarrassment.

Until Operation Diana, Mullett and Ashby cultivated influential relationships in Victorian policing and politics. They had identified their professional enemies - among them Nixon and the other contender tipped to succeed her, Simon Overland - and shared intelligence on their flaws.

We know this because the OPI had been bugging Ashby's phones, his office, his wife's phone and the phones of his teenage son and daughter. Undercover agents from interstate agencies were recruited to follow him to and from his workplace at Victoria Police Centre, to coffee meetings (where the sugar bowls were fitted with electronic listening devices), and hotels.

For months, the OPI combed Ashby's personal and professional life and, subsequently, the private conversations of his children without him suspecting he was a target of anything.

His office was entered and searched by an OPI investigator without a warrant late one night so that his diary could be removed, copied and returned without his knowledge, while every word of his often colourful expletive-riddled conversations, in which he criticised the judgment and operational experience of Overland, was transcribed.

Ashby and Mullett were the OPI's most significant scalps by a big margin. Their humbling was supposed to signal to the public that the OPI had come of age as a serious agency targeting police corruption, and it silenced some critics who wanted a royal commission and a permanent agency that would not limit its investigations to police, but would also be empowered to investigate corrupt politicians and public servants.

The demise of Ashby and Mullett was also a convenient outcome. The OPI, Nixon, and those closest to her, were staunchly and openly opposed to Mullett, who stood up against her reform agenda and accused her on behalf of his members of turning Victoria Police into a bureaucracy to the detriment of its operational capacity.

Mullett had regularly, and publicly, lampooned the OPI as a retarded Spanish Inquisition, and he deeply resented the roles of both the OPI and Nixon in having him repeatedly investigated over allegations made by members of an opposing faction in his union that he was a tyrannical bully.

Sources have told The Australian that senior OPI figures "absolutely hated" Mullett. Before Operation Diana, the OPI had a strongly adverse view about him and it had made this plain in its report on his alleged bullying.

Mullett also suspected that the OPI was a serial leaker to the media of confidential information against police. As a detective, Mullett's crime-fighting skills and bravery were the stuff of legend, earning him two valour awards, but he regarded OPI investigators as amateurs.

His relationship with Ashby, something Nixon had encouraged by asking Ashby to become closely involved in 2007 enterprise bargaining negotiations with Mullett, meant the two men spoke often on the telephone.

Ashby believes the relationship painted a target on his back with the OPI.

As Australia's newest and most inexperienced agency empowered to combat wrongdoing by police, the OPI has been Victoria's standing substitute for a broad, cleansing and transparent royal commission that Premier John Brumby and his predecessor Steve Bracks have refused to establish in spite of numerous pleas from eminent retired judges and corruption fighters.

Having armed the OPI with extraordinary powers while lowering the bar on the OPI's accountability, leaving its operational decisions and modus operandi effectively exempt from formal oversight, Labor politicians and the heads of Victoria Police - from Nixon to the man who succeeded her, Overland - have repeatedly expressed confidence in the OPI's capabilities.

The OPI, in turn, has been determined to ensure that powers and funds bestowed on it are put to good use. It needs scalps.

It is, on its face, a potentially dangerous set of circumstances for a newly invented agency: the OPI is under enormous political, community and media pressure to prove its effectiveness by taking on bent cops; it is guaranteed political patronage derived in large part from the Victorian government's rejection of the alternative of a broader anti-corruption body that could investigate political and public sector corruption; it enjoys sweeping coercive powers that remove the right to silence and prevent people being called to the OPI for secret hearings under oath from disclosing anything to anyone other than their lawyer; it enjoys operating without scrutiny of its methods and motives; and it has recruited many staff with limited experience as investigators.

In this environment, say Ashby and Mullett, an open inquiry is needed to ensure the OPI can be trusted to follow the rule of law and not to run investigations for political or other purposes.

An OPI spokesman declined to comment yesterday.