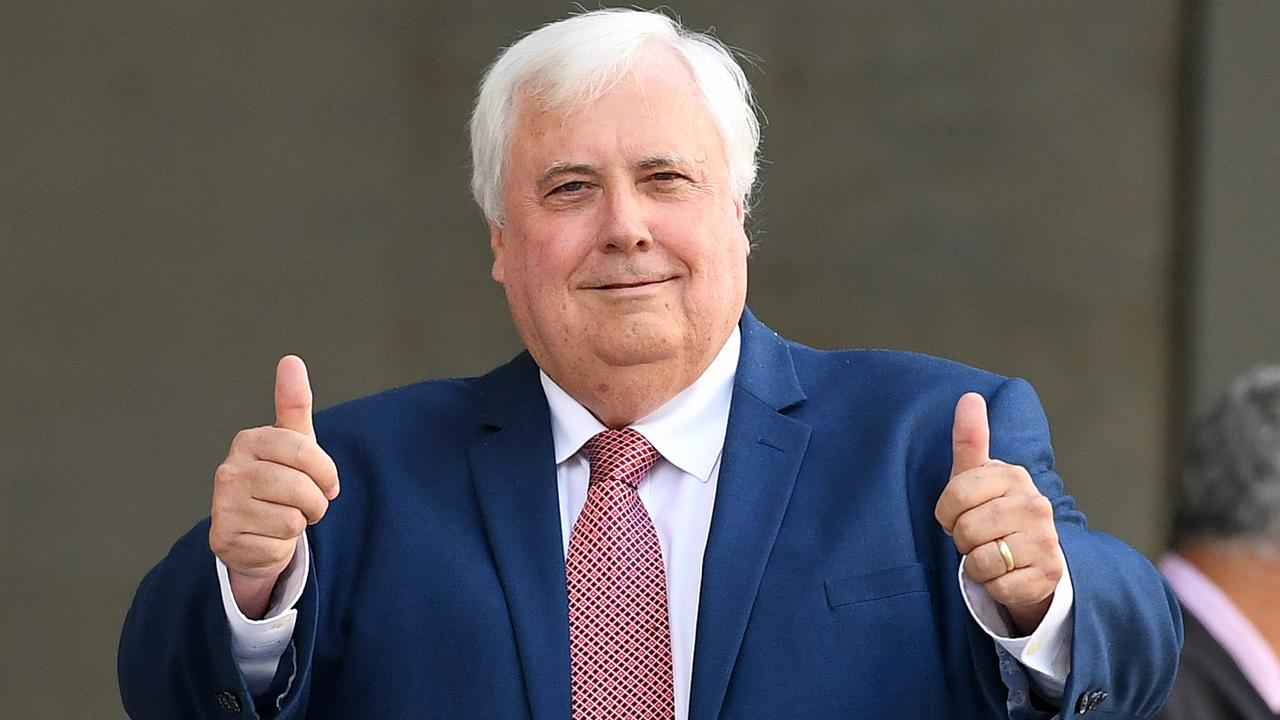

Clive Palmer ‘wanted to hang on to cash’: Clive Mensink

Clive Palmer went cap in hand to the Queensland government for a bailout of his nickel refinery because ‘he did not want to pay’.

Clive Palmer went cap in hand to the Queensland government for a taxpayer bailout of his nickel refinery not because his companies could not afford it but because he did not want to pay, his nephew has revealed.

During cross-examination in the Queensland Supreme Court yesterday, Clive Mensink conceded Queensland Nickel’s creditors would “probably” never be paid the $300 million they were owed after the company’s collapse. He admitted the refinery’s complex corporate structure meant his uncle, Mr Palmer, a federal MP and businessman, could legally dodge paying the debts to employees and suppliers.

An attempt by Mr Palmer’s companies QNI Metals and QNI Resources — the joint-venture owners of the cash-strapped Townsville nickel refinery — to slap injunctions on QN’s administrators yesterday appeared to backfire, as Mr Mensink was forced into the witness box to be cross-examined.

The Palmer-controlled companies are attempting to block demands from administrators FTI Consulting to pay $190m in debts incurred by QN. Mr Palmer is also trying to stop receivers being appointed to QNI Metals and QNI Resources, which could lead to a raid on the companies’ assets. Mr Mensink is the sole director of all of the businesses.

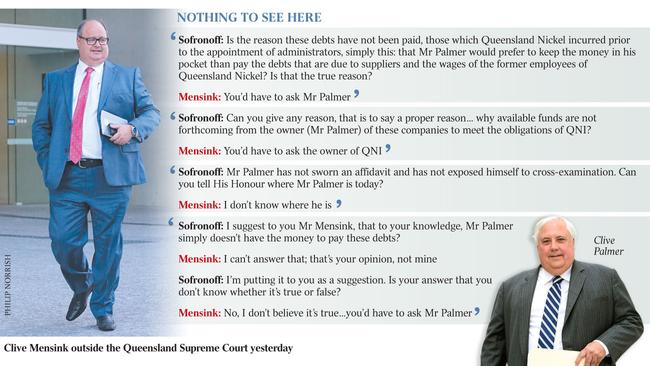

In court, veteran silk and former Queensland solicitor-general Walter Sofronoff QC, for FTI, asked Mr Mensink, the refinery’s then managing director, why Mr Palmer’s joint-venture companies did not shell out to keep the refinery afloat if they had the money, instead of seeking taxpayer bailouts and bank loans late last year.

Mr Sofronoff: “(Is) the reason the debts of Queensland Nickel remain outstanding … because the joint-venture partners don’t have the money to pay, or because they have the money but choose not to pay them?”

Mr Mensink: “Well, they don’t want to pay them.”

Mr Sofronoff: “You don’t want to pay them? Why not?”

Mr Mensink: “Because, at the moment, at the time, it was losing a lot of money.”

Later, Mr Mensink admitted that creditors of QN would “probably” never be repaid all of the money owed to them.

The barrister then turned his attention to Mr Palmer, the ultimate owner of all of the companies, and his absence from court.

The federal MP was not exposed to cross-examination because he did not file an affidavit, as Mr Mensink did.

Mr Sofronoff: “Is (it) that Mr Palmer would prefer to keep the money in his pocket than pay the debts that are due to suppliers and the wages of the former employees of Queensland Nickel? Is that the true reason?”

Mr Mensink: “You’d have to ask Mr Palmer.”

Later, Mr Sofronoff suggested Mr Palmer — a self-proclaimed billionaire — simply did not have the money to pay the debts. Mr Mensink batted away the volley. “No, I don’t believe (that’s) true … you’d have to ask Mr Palmer.”

Mr Palmer did not answer The Australian’s questions, but has repeatedly denied any responsibility or wrongdoing in relation to QN’s collapse.

Mr Mensink told the court that due to a historic joint-venture agreement outlining the corporate structure of the refinery, Mr Palmer and his companies could strip profits and incur debts at the refinery, but avoid liabilities and keep trading simply by changing the management company.

“The agreement does allow that, yes,” he said.

This corporate switch occurred in March, but failed to keep the refinery afloat. The court heard that Mr Palmer secured $23m in conditional finance from Sydney-based non-bank commercial lender Chifley Securities for his botched rescue plot.

The court heard that maintenance at the Yabulu plant was in a parlous state. Mr Mensink admitted he had received an engineering report that warned a tall exhaust stack was at risk of collapsing within one year. However, he did nothing to fix the stack.

“We just hadn’t got around to fixing it,” Mr Mensink said. He added that workers were told not to go too close to the structure.

“At that stage, I was busy, trying to secure funding for the refinery,” he said.

The hearing aired new details of QN’s creditors. The court heard that when QN collapsed into administration the company had debts of at least $53m to unsecured creditors. About $7m was owed to New Caledonian nickel concentrate supplier Vale, while Singapore-incorporated Trafigura was owed about $600,000 for fuel oil it supplied to the refinery.

The court heard that rail group Aurizon was owed $7.8m by QN in November. In March, by which time Aurizon was owed about $18m by QN, it terminated rail contracts with the refinery.

Creditors are expected to vote to liquidate QN at a meeting in Townsville tomorrow. Queensland Supreme Court judge Martin Burns reserved his judgment.