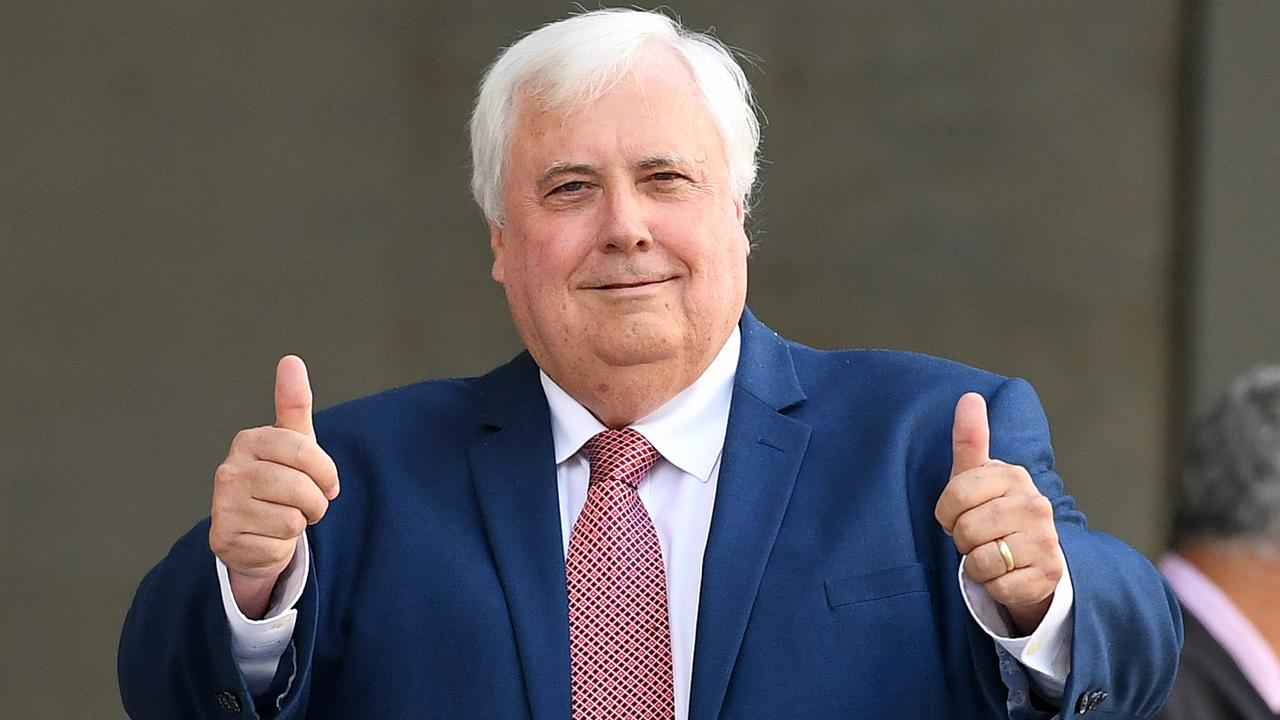

Clive Palmer in frame for $60m clawback of donations and loans

Administrators want to claw back at least $60m in donations and loans from Clive Palmer’s Queensland Nickel refinery.

Clive Palmer’s teetering business empire is under increasing pressure as administrators investigate clawing back at least $60 million in donations and loans from the MP’s Queensland Nickel refinery to other Palmer-controlled companies.

Preliminary forensic analysis of the Townsville refinery’s books is understood to reveal Queensland Nickel acted as a cash cow for the Palmer group of companies, helping to prop up enterprises such as the Palmer United Party and his ailing Coolum golf resort.

Voluntary administrators FTI Consulting — appointed by QNI on Monday after 237 workers were sacked last Friday — are scrutinising whether any of the payments were uncommercial transactions and could be forcibly retrieved, should the nickel operation collapse into liquidation.

Controversy surrounds more than $21m in political donations from Queensland Nickel to Mr Palmer’s political vehicle in the past two financial years, including one of $288,516 made amid financial strife late last year. The refinery’s most recent set of financial accounts also shows that Queensland Nickel “forgave” $38.3m in loans to other companies owned by Mr Palmer in 2014-15, following on from $6m in forgiven loans in 2013-14.

Investigations are believed to have found Mr Palmer at the helm of a complex web of companies and loan accounts, and the refinery acting as a “cash flow business” for the benefit of other Palmer entities.

The company’s move to sack the 237 workers left it with a bill of up to $16m in unpaid redundancy entitlements that Queensland Nickel does not have the cash to meet. That decision, along with others made during the company’s final months, will be closely examined to ascertain whether Queensland Nickel was trading while insolvent. There will be no more job cuts in the short term. Queensland Nickel collapsed into administration with debts of about $70m. Rail operator Aurizon is the biggest unsecured creditor, owed about $20m, while redundant workers have the next largest claim. Workers will be given priority over other unsecured creditors.

Mr Palmer, who faces the prospect of losing his seat in federal parliament if he is declared bankrupt, will register himself as an unsecured creditor after using $2.5m of his own money to pay workers over Christmas.

The Australian revealed yesterday that two Palmer-controlled companies — China First and Waratah Coal — lodged claims on the Personal Property Securities Register to become secured creditors over all of Queensland Nickel’s assets four days before it sank into administration. Corporate lawyers and insolvency experts said the move could be interpreted as an attempt by Mr Palmer’s interests to leapfrog the claims of other creditors, including workers.

Queensland Nickel executives insist both companies have not yet provided financial assistance to the refinery, and are not considered secured creditors. If the Palmer companies do stump up cash or assets to prop up the refinery and the operation then falls into liquidation, China First and Waratah Coal would be thrust into the fight over QNI’s assets.

There was also a flurry of directorship changes across Mr Palmer’s network of businesses during Queensland Nickel’s final days. Clive Mensink, Queensland Nickel’s managing director and Mr Palmer’s nephew, resigned his directorships of some Palmer-related companies and was replaced by Mr Palmer’s wife, Anna.

As anger continued to build among current and former refinery workers, Mr Palmer accused Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk and the LNP opposition of using the refinery crisis to politically grandstand. He also said “untrue and alarmist” reporting by media outlets owned by News Corporation — publisher of The Australian — was driven by a vendetta of Rupert Murdoch after Mr Palmer called his ex-wife a Chinese spy.

“Queensland Nickel is a serious issue, not a political football,” Mr Palmer said. “We continue to see media misrepresentation about the refinery. The media are fuelling political debate on the issue when it is a matter that is seriously challenging QNI and the people of north Queensland.”

He said he would not comment further until after the first meeting of creditors in Townsville next Friday.

Mr Palmer and Mr Mensink have blamed the Queensland government for the refinery’s financial woes after Treasurer Curtis Pitt refused to allow the government to act as guarantor for a $35m bank loan to the refinery.

The Australian understands Mr Pitt’s representatives will meet administrators next week, when FTI will seek to discuss government assistance.

QNI needs a cash injection for it to survive until along-awaited improvement in the nickel price.

Australian Workers Union northern district secretary Rod “Cowboy” Stockham said current and former refinery workers were growing increasingly frustrated.

“For (the 550 remaining refinery) employees, there’s an equal amount of frustration and fear,” he said. “The first thing (redundant) workers want to know is ‘Any work around?’ and the second is ‘How are we going to get our (redundancy) money?’ ”

Sacked workers will not receive redundancy entitlements until creditors agree on a deed of company arrangement, or the company goes into liquidation. If the latter occurs, workers can access the federal government’s Fair Entitlement Guarantee safety net scheme, which pays out entitlements at a capped rate.

The interwoven nature of the financial interests of Mr Palmer’s companies and the importance of inter-company loans to the functioning of his business network was highlighted in a sworn affidavit last year by Daren Wolfe, chief financial officer of Queensland Nickel and the group financial controller for a host of Mr Palmer’s private companies.