Xi Jinping, Peter O’Neill build China-PNG ties

When PNG hosts the APEC summit in November, the star of the show will be Xi Jinping — the new giant bestriding the Pacific.

When Papua New Guinea hosts the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation summit, its biggest international event since gaining independence 43 years ago, the star of the show will be Chinese President Xi Jinping — the new giant bestriding the Pacific.

That’s assured, with US President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin announcing that neither of them would be flying to Port Moresby to participate on November 18.

Xi — the new hero of the global elites, recently eliciting glowing praise from African leaders who gathered in Beijing — is relentlessly building credit, in all senses, in the Pacific. He has scheduled a bilateral state visit to PNG immediately before the APEC summit.

PNG’s Prime Minister and dominant politician, Peter O’Neill, is inviting leaders of the other 13 independent Pacific island countries to join in the APEC festivities. And he is allowing Xi to use PNG as a platform to host his own summit of Pacific states during his visit.

Scott Morrison also will try to get into the act by hosting a barbecue for the island leaders at the high commissioner’s residence overlooking the harbour.

Xi will use his visit to intensify Beijing’s campaign to lure away the six Pacific countries, represented at the Port Moresby gathering, that recognise Taiwan diplomatically.

The poorly received stomp-out by Chinese diplomat Du Qiwen during this month’s Pacific Islands Forum in Nauru, a Taiwan ally, has made that task tougher, however. It may be no coincidence that O’Neill declined to attend the annual PIF leaders’ meeting. Fijian Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama, an even more frequent visitor to China, also stayed away.

Their absence may have been intended to be read by Beijing as subtle solidarity.

Morrison also was a no-show in Nauru, though he had the excuse of having only just ascended to the top job. He is a certainty for the APEC summit in Port Moresby and has visited PNG before, including as immigration minister bedding down the Manus Island deal originally signed between the Rudd and O’Neill governments, and to walk the craggy Kokoda Track with Labor’s Jason Clare, now opposition spokesman on trade and investment.

Xi is expected to make a big announcement or two about PNG and the Pacific in Port Moresby, where he will arrive two days before most other leaders. That may include negotiating a free trade agreement with PNG, said by China’s commerce ministry to be “under consideration”.

It also may include a gigantic infrastructure commitment — which would be particularly momentous if it involves a project to finally link the capital, which still lacks direct links to any other major centre, with PNG’s Highlands Highway spine. This has been foreshadowed in vain several times before — with Japan putatively involved 15 years ago, and China more recently, but so far without a concrete result.

Anticipating closer relations with Beijing as a result of the Xi visit, PNG has announced that all Chinese government officials and tour groups will be able to obtain visas on arrival in PNG — complementing national carrier Air Niugini’s plans to launch direct flights to Shanghai.

Ahead of PNG’s National Day last Sunday, marking the nation’s independence from Australia in 1975, O’Neill welcomed Chinese politburo member Li Xi, the Communist Party secretary of the powerhouse southern Guangdong province, saying: “Sub-national engagement with provinces in China is important for building more business and investment in PNG.”

He welcomed investors from Guangdong to explore opportunities in many sectors, including resources, agricultural products and student exchanges.

The PNG government does not appear to be too concerned about its burgeoning debt, an increasing amount of it — more than $2 billion — already owed to China.

The approach to debt of many PNG politicians — including, it now appears, former accountant O’Neill — has been that the country will keep exploiting ever grander resource deposits and thus stay a step ahead of its creditors.

In terms of the headline projects, Bougainville was followed by the OK Tedi copper and gold mine and the Porgera Gold Mine, then by the first oilfields pioneered by Oil Search in the Southern Highlands and the Lihir goldmine, and more recently by the first major liquefied natural gas plant, with a second now being teed up.

PNG’s long-time development theory has envisioned that the people who live in the vicinity of a project would be the primary beneficiaries in terms of royalties and jobs, while the country as a whole would gain from the growing tax income, funding education, health and infrastructure for the country to attract broad-based sustainable investment, and thus more jobs.

That’s the dream. But it has yet to become the reality. Essentially, governments have overpromised and then failed to deliver.

China has become the latest “headline project” source of such revenues. And so far, so good. The money has indeed been flowing, accompanied by large numbers of Chinese workers and others — not all of them intending to return to their motherland before they have earned their fortune.

The preferred route for many of the new Chinese arrivals is to save like crazy and then go into business, overcoming through swiftly built guanxi — networks — the inevitable visa hurdles.

Thus a large proportion of PNG’s lowest level retail businesses — tiny shops and fast-food joints known locally as “tucker boxes” — have been delocalised by this recent wave of Chinese arrivals, many of whom do not speak English or Tok Pisin, PNG’s lingua franca.

Mekere Morauta — an opposition MP and former prime minister, finance secretary and central bank governor — says: “We have signs of Chinese domination already in the conduct of public finance and structure of the economy, and with Chinese doing the jobs of Papua New Guineans: driving trucks, bulldozers, tractors, sweeping roads, opening trade stores in every corner of the country. What is next?”

There is inevitably tension between perceptions of this rapidly growing China enmeshment by the large numbers of unemployed or scarcely employed Papua New Guineans on the one hand, and those of the PNG elite, many of whom have visited China as guests of Beijing and who increasingly look to China as their deus ex machina — their personal and corporate way out of any number of problems.

The attitude in PNG to the APEC summit reflects this bifurcation.

While it is perceived as a source of national pride and personal opportunity by much of the elite, outside Port Moresby it is widely seen, in the local parlance, as samting bilong Mosbi tasol — something affecting only the capital.

Within Port Moresby, despite the new highways and the road resurfacing — on which China has spent $82 million, with the work done by its own companies — and the new Chinese convention centre for the summit, costing $35m, many people are fed up with the rerouting and the disruption, including the temporary closure of some popular markets.

The mood is similar to that of many inhabitants of Brisbane during preparations for the G20 summit in 2014, with little expectation of significant lasting benefit.

Some typically irreverent PNG wits refer to it not as APEC but as Apekpek — pekpek is the Tok Pisin term for excrement.

China’s infrastructure program for PNG — each element, however small, being prominently badged as part of the new China Aid organisation — is framed as a part of the Belt and Road Initiative, whose bold infrastructure projects are intended to be driven by business plans involving loans rather than grants.

The risk is a steady deterioration in the overall relationship if the money does not flow back as agreed or if the projects falter.

This is what happened with the PNG projects undertaken by Australia’s biggest resource developers, Rio Tinto (Bougainville) and BHP (OK Tedi), which at first were viewed as transformative for the young country’s national development. Both turned sour in different ways, and neither company has any significant presence in the country nowadays.

The state-owned giant China Metallurgical Group Corporation (MCC) has developed the $2.6bn Ramu nickel and cobalt mine in Madang, which at last began producing four years ago after the company was shaken by the capacity of legal challenges to halt a deal despite strong government backing.

The courts held the operation up for years over environmental and landowner concerns, demonstrating how the rule of law must be taken seriously in a country that, for all its troubles, largely retains separation of powers.

The project demonstrates Chinese learning capacity, with MCC also benefiting from advice from Brisbane-based Highlands Pacific, which holds an 8.56 per cent stake in the joint venture.

More Chinese companies are now seeking access to PNG’s resources or rural products, or are keen to develop construction projects using soft loans from the government in Beijing.

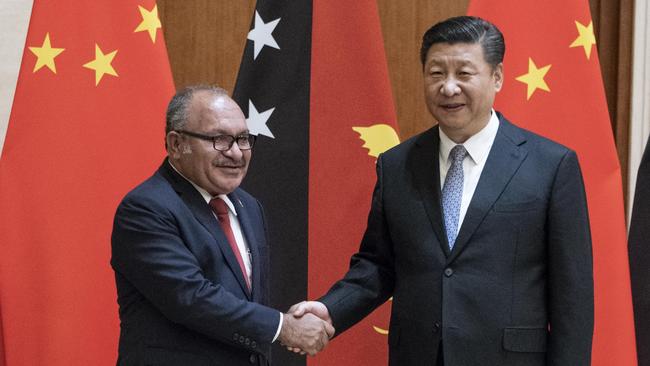

In June, in part to cement Xi’s commitment to attending the APEC summit, O’Neill led a delegation of about 100, including 19 government officials and 50 PNG-based Chinese businesspeople, to Beijing on a chartered Air Niugini plane.

After meeting Xi in the Great Hall of the People, O’Neill — likely to retain power until the next election in 2022 — declared: “Papua New Guinea is committed to deepening its strategic partnership with China, firmly pursuing the one-China policy.”

The top goal of the one-China policy is to delegitimise the idea of an independent Taiwan.

O’Neill also said he was “highly praising and actively supporting” Xi’s signature BRI scheme.

The BRI program contrasts clearly with the biggest target of Australia’s aid — $572m this financial year — to improve the nation’s governance.

China is building strong connections with PNG leaders from every party and faction, with government officials in the capital and all provincial centres, and — especially intimately — with all PNG state-owned firms. The police commissioner this year led a delegation of senior officers to China for a week’s study tour plus a week of sightseeing.

While Canberra has supplanted, for $131m, Chinese telecommunication giant Huawei’s ambition to build an internet cable link between PNG and Australia, the PNG government appears ready to revive a deal with Huawei to build key domestic connections — although Canberra may wish to seek to replace the Chinese company in that project, too.

Lae, PNG’s biggest port, recently has been redeveloped by China Harbour Engineering, via an Asian Development Bank tender, and now the government is looking to China to do the same for four smaller ports at Wewak, Kikori, Vanimo and — especially strategic given its location straddling the North Pacific and the South Pacific — Manus.

This month, China’s busy state corporations have been gaining publicity in PNG by further cementing their connections.

A CHE executive told school students the company would provide scholarships to study in China, while China Wu Yi, which wants access to land for rice production, donated tractors to the Eastern Highlands government for rice and mushroom production.

O’Neill says: “We have no competing interests over geopolitics or political issues.”

He says his government only wants “to improve the standard of living for our people and to do the best deals”.

But he has become exasperated with the failure of Canberra — whose aid this year totals about 8 per cent of the PNG budget — to respond to his repeated appeals to reduce the burden faced by Papua New Guineans seeking Australian visas.

He told his parliament last week: “After 43 years of nationhood, the people of PNG are entitled to expect the relationship with our closest neighbour to be one of maturity and respect … Our country has a rising middle class. These are people who work hard and want to have a holiday or do business in Australia, but instead they spend their money in Asia because they are treated so badly by the Australian process.”

University of PNG academic Patrick Kaiku warned soon after: “Australia conveys a patronising image of the Pacific when citing the China threat. Labelling the islands as ‘our patch’ or ‘our sphere of influence’ is an unproductive message.”

He said condescending rhetoric “will push Pacific political elites towards China”, while building long-term partnerships with PNG and other leaders and civil societies would develop “a powerful ally when corrosive effects of China’s debt-trap diplomacy or militaristic agendas need confronting”.