Typical pugnacious performance from man who won’t go quietly

Malcolm Turnbull always knew he was likely to be taken out of the prime ministership in a box.

Malcolm Turnbull always knew he was likely to be taken out of the prime ministership in a box, and yesterday he made it clear he would go down fighting.

He accused his enemies in the Liberal Party — no need to name his nemesis, Tony Abbott — of bullying colleagues in a relentless insurgency to pull the party further to the Right.

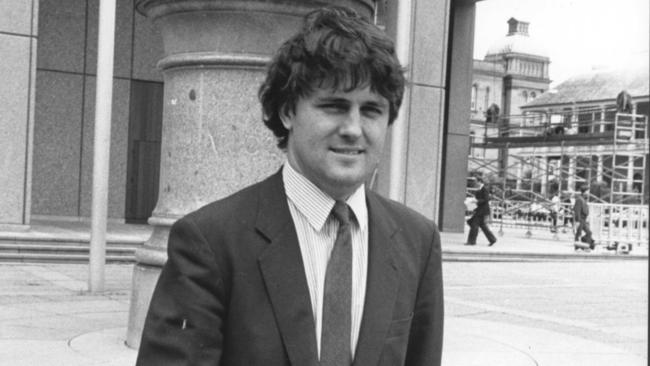

It was a typically pugnacious performance. Despite his posh schooling, his Rhodes scholarship and his barrister’s waffle, Turnbull has always been an all-out streetfighter, ambitious protege of media mogul Kerry Packer and NSW Labor premier Neville Wran.

MORE: Turnbull’s ruthless road to revenge

Had that fighting spirit been evident through his time as Prime Minister, it might not have come to this. But Turnbull has been kept on a short lead for the past three years.

As a young journalist for The Bulletin, Turnbull wrote: “There’s nothing the matter with being vicious. In fact there is not nearly enough venom and malice in this pussy-footing society of ours.”

That aggression manifested itself in the kind of dice-rolling that propelled his career in the law, business and politics: battling Margaret Thatcher’s government in the Spycatcher case; skewering Packer’s bid for Fairfax in 1991; bringing out wads of his own cash to barge his way into preselection and parliament; tearing down two Liberal leaders, in Brendan Nelson and Abbott.

Turnbull’s aggression was born of the high expectations of his mother, Coral Lansbury, who abandoned him when he was eight, parting with his father and moving overseas. Lansbury used to joke with her friend Dame Leonie Kramer about whose son would become prime minister first. On the ABC’s Australian Story in 2009, Turnbull reflected that perhaps he had tried so hard in life because he was trying to win her back.

As Turnbull’s old editor Trevor Kennedy — later co-investor in a string of dotcoms, including OzEmail, which made them both rich — toasted him at his 30th birthday: “Malcolm probably wouldn’t even be satisfied with being prime minister of Australia. He’d probably rather be prime minister of the world!”

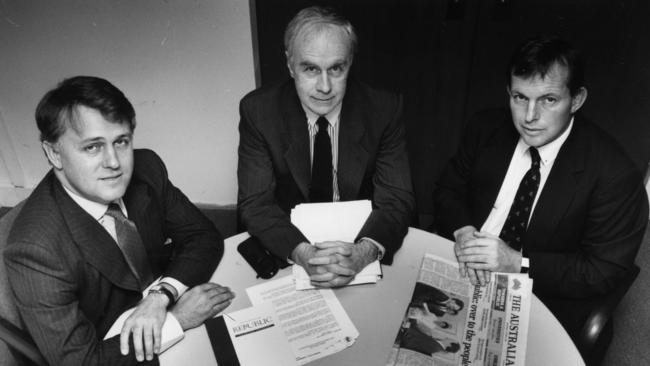

Turnbull’s appetite for risk also led to epic defeats: spending millions on the Australian Republic Movement, which went down in the 1999 referendum; staking his leadership on the concocted claims of Treasury mole Godwin Grech.

Turnbull took the prime ministership on terms that did not allow him to be himself. They were buried in the secret agreement between the Liberals and Nationals, never revealed to the public, which stopped Turnbull taking serious action on climate change, going soft on border protection, allowing a free vote on marriage equality or reopening the republic debate.

No doubt he would say it was all worth it. He took over as Prime Minister three years ago, brimming with enthusiasm. These were the most exciting times in human history. He promised an end to shouty politics, with adult conversations about difficult decisions. The sensible centre. The public responded with goodwill and soaring polls. Had he called an election in early 2016, Turnbull might have won a thumping mandate that would have allowed him to break the shackles and remake the party in his own mould.

Instead, he baulked — at an early election; at GST reform; at anything much beyond good cabinet government and jobs and growth. The public, realising they were not getting the

Turnbull they thought they knew, lost interest. Just another politician.

Prime ministers do grow into the job. In the wake of his narrow 2016 victory, there have been glimpses of something new: Turnbull the statesman, wrangling US President Donald Trump, attempting a tense diplomatic reset with China. Last week, at the launch of an essay on Australia’s relationship with Indonesia, a high-powered panel spoke with feeling about the Prime Minister’s friendship with President Joko Widodo.

But Turnbull, like Julia Gillard, has never been able to escape from the manner of his ascension to the top job. Abbott, like Kevin Rudd, was never going to go quietly.

In the end, ironically, Turnbull has lost the Lodge for failing to roll the dice, for capitulating. In his backdown on the national energy guarantee last Friday, Turnbull gave his enemies everything they wanted, again, and they knifed him anyway. In fact they knifed him because of it.

As he sat at the dispatch box yesterday, for almost certainly his last time, Turnbull had a low-voiced conversation with his opponent Bill Shorten. There was even a smile. It was hard not to wonder what was said, and ponder whether Turnbull might have been more at home on the other side of the house. For many Liberals, the Wran protege, Keating Republican and Rudd emissions trader simply was never in the right party.

Whether the blame lies with Abbott’s insurgency above all, or with Turnbull’s own flaws, the Prime Minister’s inability to unite and lead the Liberal Party has reduced the parliament to chaos. It is all about him.

Paddy Manning is author of Born to Rule: The Unauthorised Biography of Malcolm Turnbull.