Trump’s Iran gambit alienates his allies

There is little to be gained from Donald Trump’s decision to exit the Iran nuclear deal.

The latest episode of Donald Trump’s wrecking-ball approach to the Middle East and his Western allies played out yesterday as he opted out of the multilateral nuclear agreement with Iran so painstakingly negotiated by his predecessor in partnership with the other permanent members of the UN Security Council and Germany. There is little doubt that the authors of the agreement were one of his targets.

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action was perhaps the signature foreign policy achievement of the Obama administration, and that alone appears to have been sufficient reason to nix the deal.

Because outside of petty vindictiveness there is little to be gained from Trump’s decision. Indeed the opposite is likely to be true. The agreement came about because it was felt that the multilateral sanctions regime in place, while effective, could not be maintained forever. It had achieved its purpose by bringing Tehran to the negotiating table and it was time to gain a tangible policy outcome from those sanctions.

The agreement had limitations that all signatories acknowledged and accepted. But it was signed nevertheless, and Trump’s own State Department and the International Atomic Energy Agency have both confirmed that Tehran is abiding by the agreement. It is a rare outcome indeed that is able to hand Tehran the moral high ground, yet Trump has somehow managed to achieve this by pulling out of an agreement that all signatories agree is being complied with.

The public justifications for taking this action had little to do with his own political calculations for doing it.

During his speech Trump cited Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s anti-Iran television presentation (given in English) last week when he said: “Today, we have definitive proof that this Iranian promise (that their nuclear program was for peaceful purposes) was a lie. Last week, Israel published intelligence documents — long concealed by Iran — conclusively showing the Iranian regime and its history of pursuing nuclear weapons.”

The trouble with this, though, is that the salesman and the product were both suspect. The information was largely a rehash of what was already known and understood years ago, before the negotiations were undertaken.

And Netanyahu, who is facing his own domestic political problems, has some credibility problems when it comes to foretelling outcomes in the Middle East.

Speaking before the US congress in 2002, while trying to convince the US about the threat posed by Saddam Hussein, he claimed: “There’s no question that (Saddam) had not given up on his nuclear program ... every indication we have is that he is pursuing, pursuing with abandon, pursuing with every ounce of effort, the establishment of weapons of mass destruction, including nuclear weapons. If anyone makes an opposite assumption or cannot draw the lines connecting the dots, that is simply not an objective assessment.” Adding an optimistic flourish to his claims, he declared: “If you take out Saddam, Saddam’s regime, I guarantee you that it will have enormous positive reverberations on the region.”

Looked at objectively, it isn’t exactly clear what Trump is trying to achieve, because there is no US policy that has replaced the JCPOA. In his speech he claimed that “we will be working with our allies to find a real, comprehensive, and lasting solution to the Iranian nuclear threat (including) efforts to eliminate the threat of Iran’s ballistic missile program, to stop its terrorist activities worldwide, and to block its menacing activity across the Middle East”.

Any of these aims could have been achieved by staying in the nuclear agreement.

What Washington is left with is a series of current and previously existing unilateral sanctions that were never comprehensive enough to force Tehran to negotiate on their own, and a group of close allies who urged Trump not to leave the deal.

The US had to painstakingly build up an international consensus on multilateral sanctions to change the direction of Iranian policy. Trump is philosophically unwilling and his close advisers incapable of building up any form of consensus that may force Iran to negotiate in the foreseeable future.

His European partners are pretty upset, albeit in a muted European kind of way. The joint press statement from British Prime Minister Theresa May, French President Emmanuel Macron and Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel was about as forthright a criticism of Trump as one sees in these type of diplomatic messages.

When three of your closest allies state, “It is with regret and concern that we, the leaders of France, Germany and the United Kingdom, take note of President Trump’s decision to withdraw the United States of America from the joint comprehensive plan of action”, it is hard to be optimistic of any of Trump’s negotiators finding much co-operation from Europe.

Even in Canberra, Foreign Minister Julie Bishop expressed “disappointment”, and Malcolm Turnbull added his “regret”, over the decision.

It was difficult to determine whether Trump thought he was going to achieve a renegotiated deal with the Iranians, because in his own mangled way he managed to say both things. In his speech he claimed: “Iran’s leaders will naturally say that they refuse to negotiate a new deal. They refuse, and that’s fine. I’d probably say the same thing if I was in their position. But the fact is, they are going to want to make a new and lasting deal, one that benefits all of Iran and the Iranian people.”

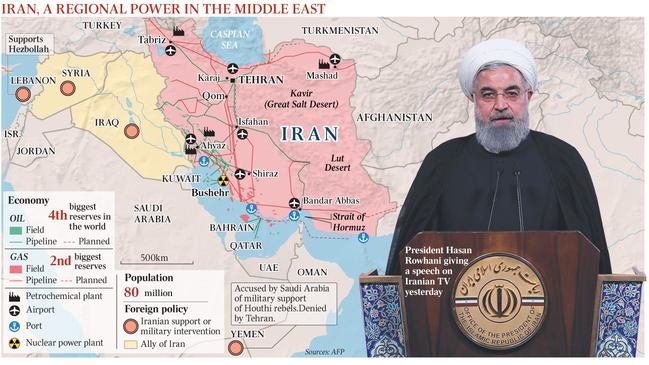

Regardless of whether Trump believes they will or won’t negotiate, there are absolutely no incentives for Tehran to negotiate. President Hasan Rowhani and Foreign Minister Javad Zarif exhausted their domestic political capital in cementing the JCPOA. Their conservative political enemies will be using the American withdrawal to beat Rowhani and Zarif over the head with politically, and all parties will simply reaffirm the anti-US narrative that Washington can never be trusted.

Iran has a few cards left to play, though, and Iranians have the patience and foresight that the White House lacks. Rowhani is under enormous domestic pressure to minimise the fallout from Washington’s withdrawal. He desperately needs the foreign investment that the deal was designed to usher in, but he also needs to reassert Iranian resolve in advance of discussions with the European signatories. Hence his dual approach to the issue in the short term.

He has held out the prospect of abandoning the deal if need be, saying: “If needed, we will resume our nuclear enrichment at the industrial level without any limit. From now on, everything depends on Iran’s national interests.”

There is time for Tehran to rearrange things, as the complex provisions of the JCPOA mean that the removal of sanctions waivers on various types of transactions only comes into effect after 90 days in some cases and 180 in others. But the Iranian government’s preference is to remain in the deal despite Trump’s withdrawal. Rowhani’s economic challenges, particularly persistent unemployment, are immense and a discontented population is a threat to regime stability. It needs foreign investment in labour-intensive sectors. Which is why Tehran will try to negotiate around Washington to try to clarify the agreement’s utility to Iran.

Rowhani said as much when he told the public: “I have ordered the foreign ministry to negotiate with the European countries, China and Russia in coming weeks. If at the end of this short period we conclude that we can fully benefit from the JCPOA with the co-operation of all countries, the deal would remain.”

Of course there is already economic pain for Iran. Washington’s extant unilateral sanctions and uncertainty over the JCPOA as a result of Trump’s anti-agreement rhetoric haven’t done much for investor confidence and foreign investment has been disappointing to say the least. And during my recent trip to Iran the impacts of the currency crisis engendered by the same lack of confidence in the future, including capital flight and the plummeting value of the rial, were all too obvious.

A ban on official (and unofficial) currency trading came into effect just before I joined the queue to change my US dollars for rials. For Iranians who travel overseas or who seek to support family who are studying abroad and need access to hard currencies, times are hard. For Iranian youth who seek a range of worthwhile employment opportunities, times are also challenging. But Iran does have economic suitors. Anyone who has travelled to Iran over the past few years can’t help but be struck by the amount of Chinese economic activity in the country. Beijing is likely to be delighted by Trump’s vacating of the agreement and will see it as simply providing justification for further acceleration of the bilateral economic relationship.

The impact on regional security of Washington’s decision is unlikely to become apparent for some time. Israel and the usual suspects among the Gulf states (Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain) welcomed the move. But Iran will not want to give any of its critics an opportunity to scupper the possibility of Iran making the agreement work and establishing viable ways to work around sanctions through its European partners and China. And it will want to maintain the moral high ground as the aggrieved party in a dispute over an agreement that it honoured for as long as possible.

Evidence of overt military action in the Middle East on the part of Iran or increased activity from proxies above a certain level would endanger the achievement of Tehran’s bigger strategic aim. Israel will continue its increasingly aggressive targeting of Iranian military and logistics facilities in Syria, which it considers pose a potential threat to itself directly or through the Lebanese Hezbollah militia. Tehran’s response to these actions has been muted to date, but it will be interesting to see how restrained it will continue to be, particularly Tehran is unable to sustain the JCPOA.

Insofar as this move has any strategic vision, the hope from Washington may well be that increased economic pressure on Iran could lead to a popular uprising against the Iranian government and bring down the system. But this fails to take into account the nature of Iranian society.

It is a country of more than 80 million people with a strong sense of nationalism. Despite a tight regime of multilateral, UN-backed sanctions along with a fair degree of domestic economic mismanagement, it was able to develop a “resistance economy” and withstand such unified international pressure for years.

The landscape that Iran faces today is, in many ways, less threatening than it was then. While its economy is still relatively weak, the first rule of forestalling internal discontent is to externalise the threat, and Washington’s punishment of Tehran despite its adherence to the agreement makes the externalising narrative an easy one to construct.

And with its experience in sanctions circumvention, plus the lack of unity between Washington and its allies, Tehran will be doing all in its power to exploit the differences so publicly on display among Western alliance partners over this issue.

Trump’s mantra of “America first” may well have won him an election and plaudits from his base, but in the complex world of international relations, unilateralism has significant shortcomings. Washington’s Iran policy is likely to prove this once again.

Rodger Shanahan is a research fellow in the West Asia program at the Lowy Institute.