Trump sanctions could mean trade war with China

If sanctions follow tariffs, Australia could get caught in US-China crossfire.

Just before Donald Trump left for Asia in November, his hardline Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer, gathered the entire White House economics team into the room for an extraordinary meeting. He told them simply that the US-China economic relationship was “bullshit”.

According to political website Axios, Lighthizer — a key trade figure in the Reagan administration — “laid out the history of the last 25 years of US-China relations. He went through what each ‘dialogue’ was called under presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama. His point: every administration comes up with a new catchword and strategic framework to describe the US-China relationship, but the trade deficit with China just keeps ballooning by the billions.”

The 70-year-old Lighthizer, a protectionist deeply hostile to China’s state-controlled trade practices, is the driving force behind what promises to be one of the pivotal moments in Trump’s presidency — the decision to confront China on trade.

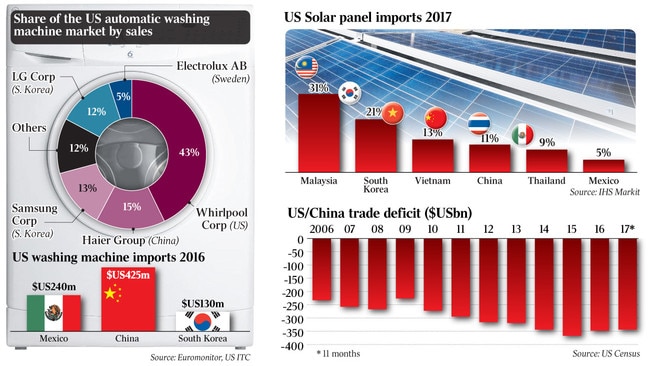

The President last week fired the first salvos in what could eventually spiral into a full-blown trade war when he slapped steep tariffs on imports of washing machines (up to 50 per cent) and solar panels (30 per cent), a move that was directed mostly at China.

But the real punch is yet to come. Very shortly, possibly within weeks, Trump is expected to unveil a long-threatened list of trade sanctions against China.

The size, extent and nature of those sanctions are unknown: they are the source of intense speculation in Washington. But they threaten to reverberate around the world — not least in Australia, which may be hit indirectly by US tariffs on steel, and more broadly by the ugly spectacle of a trade war between our major trading partner and closest ally.

In recent weeks Trump has signalled that after a year of mostly empty rhetoric on China he is now prepared to act.

There is no doubt that Trump is angry, given that the US trade deficit with China — which in 2016 was a whopping $US347 billion — is still growing larger by the month.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos last week, Trump launched a thinly veiled attack on China, criticising countries with “predatory” trade practices

“The United States will no longer turn a blind eye to unfair economic practices including massive intellectual property theft, industrial subsidies and pervasive state-led economic planning,” he said.

Tomorrow night Trump will deliver his first State of the Union address amid speculation that he will further escalate his rhetoric against Beijing, if not quite going as far as using the occasion to announce new sanctions. It has been a long time coming.

Trump came into office with the expectation that he would move quickly to impose his promised trade sanctions on China.

He had campaigned aggressively against Beijing, believing that the trade deficit allowed cheap imports to flood into the US, which in turn caused factories to close and cost American jobs.

“We can’t continue to allow China to rape our country, and that’s what they’re doing. It’s the greatest theft in the history of the world,” Trump told a rally in 2016.

He declared China a currency manipulator and threatened tariffs of up to 45 per cent on Chinese imports.

But when Trump came into office the foreshadowed trade war with China was placed on the backburner.

This was for two reasons.

First, Trump suddenly needed China’s help in trying to curb the increasingly belligerent behaviour of North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un.

“If China decides to help, that would be great,” Trump wrote among a cascade of tweets on the issue. “If not, we will solve the problem without them!”

But when Trump received advice that a major military strike against North Korea would be, in the words of Defence Secretary James Mattis, “tragic on an unbelievable scale”, the President needed China all the more.

As North Korea’s major trading partner, Beijing potentially had the clout to influence the rogue regime.

Trump courted Chinese President Xi Jinping, hosting him at his Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida and tweeting afterwards: “He is a good man. He is a very good man and I got to know him very well.”

Since then Trump has elicited co-operation from Beijing against North Korea, with China agreeing to the most sweeping UN sanctions ever put in place against the rogue regime.

While Trump has slowly upped his rhetoric on China over trade in recent months, he has been careful to do it in a way that does not disrespect Xi personally or sabotage Beijing’s help on North Korea.

The other obstacle to Trump taking early action against Beijing was the fact that his own White House was involved in an internal war over trade.

Lighthizer and Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross were early advocates of strong, if not sweeping, trade measures against Beijing. They were backed by Trump’s then strategic adviser Steve Bannon, who declared openly “we’re at economic war with China”.

Trump’s senior adviser Stephen Miller and the head of the President’s trade council, Peter Navarro, were also in favour of tough action against Beijing.

They presented the President with options ranging from steep tariffs on Chinese imports to greater export controls and the filing of new complaints against Beijing in the World Trade Organisation.

But the moderate wing of the White House, led by Trump’s National Economic Council director and chief economic adviser Gary Cohn and Treasury Department head Steven Mnuchin advised against the protectionist route.

They have warned the President that his actions could lead to a catastrophic trade war. Mainstream pro-trade Republicans in congress and leading US companies have used Cohn, in particular, as the avenue to try to advance the argument inside the White House against sweeping trade sanctions on Beijing.

“The problem in part is you got the free traders whispering in one ear of the President, you got the people like Lighthizer and Ross whispering in the other ear, and the President seems too paralysed on this,” Democratic senator Sherrod Brown says.

But in recent months, and especially now that the tax reforms have been passed, Trump’s economic team has stepped up its work on China, holding weekly meetings to thrash through the options.

The lack of action on Chinese sanctions led some to believe that Trump may have stepped back from his threats, believing the consequences for the US would be too high.

So it was a shock to many when Trump suddenly announced the first protectionist measures of his administration last week by levying tariffs on washing machines and solar products.

“The President’s action makes clear again that the Trump administration will always defend American workers, farmers, ranchers and businesses,” Lighthizer said.

“My administration is committed to defending American companies, and they’ve been very badly hurt from harmful import surges that threaten the livelihood of their workers,” Trump said as he signed the tariffs. “The United States will not be taken advantage of any more.”

Trump imposed a 30 per cent tariff on solar panels in the first year. Chinese exports of solar panels to the US soared from $US188.9m in 2007 to $US1.5bn in 2016. Within a decade China turned itself into the world’s largest manufacturer of solar products, flooding the market with cheap crystalline silicon panels.

Two US companies filed a complaint against the surge in Chinese imports, with one company filing for bankruptcy at about the same time it filed the complaint. “You know, they dump them — government-subsidised, lots of things happening — they dump the panels, then everybody goes out of business,” Trump said last week.

On washing machines, the first 1.2 million imports will face a 20 per cent tariff, with additional imports facing a 50 per cent levy, while imported parts for washing machines will also face a 50 per cent tariff.

The dispute over washing machines, which will hit South Korea harder than China, began in 2011 when Whirpool accused its South Korean competitors LG and Samsung of dumping low-priced machines in the US market.

The timing of the decisions, coming days ahead of Trump’s visit to Davos, was a sign to the globalist free trade leaders that the President was willing and ready to act on his protectionist threats.

Even so, Australian Trade Minister Steven Ciobo, speaking to The Australian from Los Angeles yesterday, said Trump’s message on trade in Davos was not as hard-edged as many expected.

“Trump’s speech in Davos was reasonably well received. It was a clarification that the US is pursuing a fair trade policy.”

But Ciobo says he shares the concerns of many that the US-China dispute is already leading to protectionist measures.

“My concern is that any escalation of protectionist sentiment will create a tougher trading environment. When you have an increase in protectionist measures, when you have an imposition of tariffs, an imposition of non-tariff measures, all you see is a dilution of trade, slower global growth and fewer jobs.”

Even so, Ciobo acknowledges he and Lighhizer share “an absolute commitment to broader trade and investment ties between Australia and the US”.

Australia is anxiously watching Trump’s next move on China. The US President will face decisions in the next 90 days on possible tariffs on steel and aluminium imports into the US.

Trump wants to impose measures to protect American workers from Chinese steel, which accounts for 26 per cent of the US market.

But Ciobo has been directly lobbying the Trump administration to protect Australia’s steel exports to the US amid fears that any US measures aimed at China will also hit Australia. He has pleaded for Australia to be exempted from any move to restrict US steel imports.

Melbourne-based company BlueScope Steel is the sole exporter of Australian steel to the US, with exports worth about $US130m each year. Australia also exports aluminium worth about $62.5m to the US each year.

Trump must also decide whether to try to levy a massive fine on China for engaging in what he believes is a grand theft of US intellectual property.

“We’re talking about big damages,” he says. “We’re talking about numbers that you haven’t even thought about.”

The problem for Trump is that while some US companies may benefit from the imposition of tariffs or quotas to protect their products from Chinese or other imports, it will also lead to less competition and high prices for American consumers.

Trump gives the strong impression that the debate within his administration is over and that he is finally ready to move ahead with one of his key campaign promises.

When asked at Davos if it might spark a trade war, he said simply: “I don’t think so, I hope not. But if there is, there is.”

Cameron Stewart is also US contributor for Sky News Australia.