Toss a ball at their feet: the success of small nations at soccer

Not all soccer success can be explained by a country’s wealth.

On a sunny Saturday afternoon, within kicking distance of Uruguay’s national football stadium, 14 seven-year-olds walk on to a bumpy pitch. They are cheered by their parents, who are also the coaches, kit-washers and caterers. The match is one of hundreds played every weekend as part of Baby Football, a national scheme for children aged four to 13. Among the graduates are Luis Suarez and Edinson Cavani, two of the world’s best strikers.

Suarez and Cavani are Uruguay’s spearheads at the World Cup, which kicks off in Russia tomorrow. Bookmakers reckonLa Celeste, as the national team is known,are ninth favourites to win, for what would be the third time. Only Brazil, Germany and Italy have won more, even though Uruguay’s population of 3.4 million is less than Berlin’s.

Suarez and Cavani reached the semi-finals in 2010 and secured a record 15th South American championship in 2011. Their faces adorn Montevideo’s soccer museum, along with a century’s worth of tattered shirts and gleaming trophies.

If tiny Uruguay can be so successful, why not much larger or richer countries? That question appears to torment Chinese President Xi Jinping, who wants his country to become a soccer superpower by 2050. His plan includes 20,000 new training centres, to go with the world’s biggest academy in Guangzhou, which cost $US185 million ($243m).

The United Arab Emirates and Qatar have spent billions of dollars buying top European clubs, hoping to learn from them. Saudi Arabia is paying to send the Spanish league nine players. A former amateur player named Viktor Orban, who is now Hungary’s autocratic Prime Minister, has splurged on stadiums that are rarely filled. So far, these countries have little to show for their spending. China failed to qualify for this year’s World Cup, and even lost 1-0 to Syria — a humiliation that provoked street protests.

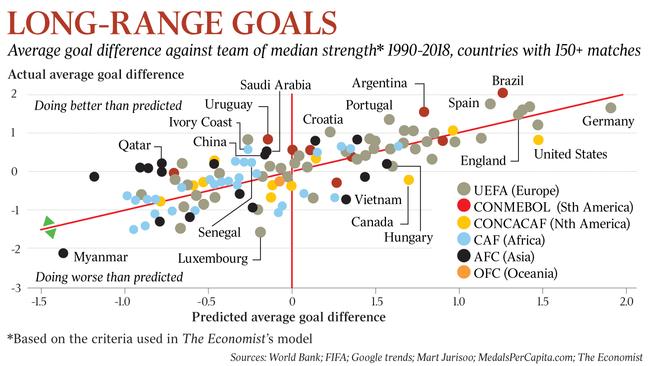

The Economist has built a statistical model to identify what makes a country good at soccer. Our aim is not to predict the winner in Russia, which can be done best by looking at a team’s recent results or the calibre of its squad. Instead, we want to discover the underlying sporting and economic factors that determine a country’s soccer potential and to work out why some countries exceed expectations or improve rapidly. We take the results of all international games since 1990 and see which variables are correlated with the goal difference between teams.

We started with economics. University of Michigan economist Stefan Szymanski, who has built a similar model, has shown that wealthier countries tend to be sportier. Soccer has plenty of rags-to-riches stars, but those who grow up in poor places face the greatest obstacles. In Senegal, coaches have to de-worm and feed some players before they can train them; one official reckons only three places in the country have grass pitches. So we included GDP per head in our model.

Then we tried to gauge soccer’s popularity. In 2006 governing body FIFA asked national federations to estimate the number of teams and players of any standard. We added population figures, to show the overall participation rate. We supplemented these guesses with more recent data: how often people searched for soccer on Google between 2004 and 2018, relative to other team sports such as rugby union, cricket, American football, baseball, basketball and ice hockey. Soccer got 90 per cent of Africa’s attention compared with 20 per cent in the US and just 10 per cent in cricket-loving South Asia. To capture national enthusiasm and spending on sports in general, we also included Olympic medals won per person.

Next we accounted for home advantage, which is worth about 0.6 goals per game, and for strength of opposition. Finally, to reduce the distorting effect of hapless minnows such as the Cayman Islands and Bhutan, we whittled down our results to the 126 countries that have played at least 150 matches since 1990.

Our model explains 40 per cent of the variance in average goal difference for these teams. But that leaves plenty of outliers. Uruguay was among the biggest, managing nearly a goal per game better than expected. Brazil, Argentina, Portugal and Spain were close behind. West Africa and the Balkans overachieved, too.

Sadly for ambitious autocrats, the data suggests China and the Middle East have already performed above their low potential. Cricket dominates Google searches in the Gulf states (no doubt largely because South Asian migrant workers love it). Just 2 per cent of Chinese played soccer in 2006, according to FIFA, compared with 7 per cent of Europeans and South Americans. China and Middle Eastern countries have occasionally managed to qualify for the World Cup, but none has won a game at the tournament since 1998.

The model’s most chastening finding is that much of what determines success is beyond the immediate control of administrators. Those in Africa cannot make their countries less poor. Those in Asia struggle to drum up interest in the sport. Soccer’s share of Google searches has been rising in China but falling in Saudi Arabia.

Nonetheless, officials with dreams of winning the World Cup can learn four lessons from our model’s outliers and improvers. First, encourage children to develop creatively. Second, stop talented teenagers from falling through the cracks. Third, make the most of soccer’s vast global network. And fourth, prepare properly for the tournament itself.

Start with the children.

The lesson from Uruguay is to get as many nippers kicking balls as possible, to develop technical skills. Xi wants the game taught in 50,000 Chinese schools by 2025. China might try something like Project 119, a training scheme for youngsters that helped to lift China to the top of the medal table at the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

The trouble is, relentless drilling “loses the rough edges that make geniuses”, says Jonathan Wilson, editor of the Blizzard, a journal covering the game around the world. East German players trained much harder than those in West Germany, but qualified for a major tournament just once.

The trick is not just to get lots of children playing, but also to let them develop creatively. In many countries they do so by teaching themselves. George Weah, now the President of Liberia but once his continent’s deadliest striker, perfected his shooting with a rag ball in a swampy slum. Futsal, a five-a-side game with a small ball requiring nifty technique, honed the skills of great Iberian and Latin American players from Pele and Diego Maradona to Cristiano Ronaldo, Lionel Messi, Neymar and Andres Iniesta.

Zinedine Zidane was one of many French prodigies who learned street soccer. In an experiment that asked adult players to predict what would happen next in a video clip, the best performers had spent more time mucking around aged six to 10.

Such opportunities are disappearing in rich countries. Matt Crocker, the head of player development for England’s Football Association, says parents are now reluctant to let children outside for a kickabout. Many social housing estates have signs banning ball games. England player Dele Alli is unusual for having learned in what he has called “a concrete cage”. The challenge is “to organise the streets into your club”, say Guus Hiddink, who has managed The Netherlands, South Korea, Australia, Russia and Turkey.

The Deutscher Fussball-Bund, Germany’s national body, has done so zealously. In the early 2000s it realised that Germany’s burly players were struggling against defter teams. Our model reckons Die Mannschaft, as the national team is known, should surpass everyone else, given Germany’s wealth, vast player pool and lack of competing sports. But between 1990 and 2005 it performed about a third of a goal worse per match than expected.

So the DFB revamped. German clubs have spent about €1 billion ($1.5bn) on developing youth academies since 2001, to meet 250 nationwide criteria. Youngsters now have up to twice as much training by the age of 18. Crucially, sessions focus on creativity in random environments. The men who won the World Cup in 2014, writes German soccer author Raphael Honigstein, learned through “systematic training to play with the instinct and imagination of those mythical ‘street footballers’ older people in Germany were always fantasising about”. Our model reckons that since 2006 the team has performed almost exactly at the high level expected of it.

England has followed, overhauling its youth program in 2012. Crocker says players are encouraged to take risks and think for themselves. Spanish clubs have long excelled at this, by endlessly practising the rondo: a close-quarters version of piggy-in-the-middle. But the England under-17s that thumped Spain 5-2 in last year’s World Cup final ran rings around their opponents. Crocker says they devised their own tactics, with little managerial help. England’s under-20s won their World Cup, too.

Such self-confidence was lacking in South Korea, Hiddink says. When he took over in 2001, the country was already overachieving relative to our model’s low expectations, given its 2 per cent participation rate. But the manager believed his charges had been held back by a fear of making mistakes. “Deep down I discovered a lot of creative players,” he says. With some help from lucky refereeing decisions, South Korea reached the semi-finals in 2002, making it the only country outside Europe and South America to get that far since 1930.

The second lesson for ambitious officials is to make sure gifted teenagers do not fall through the cracks. The DFB realised that many had been overlooked by club scouts, so it set up 360 extra centres for those who missed the cut. One of them was Andre Schurrle, who provided the pass that led to the cup-winning goal in 2014. In South Korea, Hiddink noticed some of the best youngsters played for the army or universities, where they were sometimes missed by professional scouts.

When Russia bid to host this year’s tournament in 2010, Hiddink implored his bosses to create a nationwide scouting program, to no avail. The Russian team has declined since then, failing to win a game at the European Championship in 2016.

Russia now has one of the World Cup’s oldest squads. Such short-sightedness has also harmed the US, which failed to qualify for this year’s cup. Our model reckons it should be one of the strongest countries, even accounting for the popularity of other sports such as baseball and basketball. But few players get serious coaching in the amateur college system, and those who are not drafted to Major League Soccer cannot be promoted from lower divisions.

Centralised schemes are easier to establish in small countries. Every Uruguayan Baby Football team has its results logged in a national database. Iceland, which has qualified despite having only 330,000 people and 100 full-time professionals, has trained more than 600 coaches to work with grassroots clubs. Since 2000 it has built 154 miniature pitches with undersoil heating to give every child a chance to play under supervision. Such programs are unfeasible in Africa. Former Senegal manager Abdoulaye Sarr says the pool of talent is huge but is barely tapped. Money that could be spent on scouting is lavished on officials instead. Senegal is sending 300 of them to Russia.

West Africa has, however, taken our third tip by tapping into sport’s global network. Western Europe is at the centre of this network, since it has the richest clubs, where players get the best coaching. Ivory Coast, which failed to qualify this time but is Africa’s biggest overachiever, exported a generation of young stars to Beveren, a Belgian club. Many of them later thrived in England’s Premier League. When Senegal beat France, the reigning champions, in 2002, all but two of its squad members played for French teams.

Senegal could have used its resources even more effectively. Patrick Vieira, who left Dakar for France aged eight, was playing for the former colonial power. He was one of several immigrant Frenchmen who won Les Bleus the World Cup in 1998. His home country had never contacted him. Today Senegal is more astute about recruiting its diaspora, and has picked nine foreign-born players for the tournament. Our model reckons the country has performed about 0.4 goals per game better since 2002 than before.

The 21st Club, a soccer consultancy, notes that among European countries, the Balkans export the highest share of players to stronger domestic leagues. Since 1991, when Croatia’s four million people gained independence, none of its clubs has advanced far in the Champions League. Yet Croatian clubs have sold lots of players to Real Madrid, Barcelona, Bayern Munich and Milan, and those emigres carried Croatia to the semi-finals in 1998. These export pipelines can become self-perpetuating, says Wilson: “Once a team does well at a World Cup, and some of its players do well, everybody wants to buy them.”

Some countries are less adept. In the past 15 years, Mexico’s under-17s have outperformed those from Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay. But a third of Mexico’s senior squad plays in its domestic league, compared with just two or three players for the others. National director Dennis te Kloese says the Mexican diaspora boosts viewing figures and revenues for domestic clubs, which can pay high enough wages to keep talented locals from venturing to European leagues.

Exporting players is not the only way to benefit from foreign expertise. Wilson says much of South America’s soccer education came from Jewish coaches fleeing Europe in the 1930s. Today there is a well-trodden circuit of international gurus such as Hiddink, who was among the first of a dozen former Real Madrid bosses to have worked in Asia. Yet Szymanski of the University of Michigan has shown that few managers can do much to improve mediocre teams. He also finds that teams outside Europe and South America are no closer to catching up than they were 20 years ago.

Szymanski believes these countries are experiencing a kind of “middle-income trap”, in which developing economies quickly copy technologies from rich ones but fail to implement structural reforms. A clever manager might bring new tactical fads but cannot produce a generation of creative youngsters. China is said to be paying Marcello Lippi, who led Italy to victory in 2006, $US28m a year. Unless he is supported by youth coaches and scouts who reward imaginative play, and a generation of youngsters who love the game, the money will be wasted.

Our final lesson is for the World Cup itself: prepare properly. For starters, make sure you can afford it. In 2014, Ghana brought in $US3m of unpaid bonuses by courier to avert a players’ strike.

Navigating dressing room politics is trickier. Winning players from Spain and Germany have described the importance of breaking down club-based cliques and dropping stars who do not fit the team’s tactics.

The hardest decisions fall to the players. England’s results from the penalty spot have been woeful, losing six of seven shootouts in tournaments. Video analysis shows that players who rush tend to miss penalties; the English are particularly hasty. So the under-17s, who won a shootout in their World Cup, have worked on slowing down and practising a range of premeditated shots.

The bane and the delight of the World Cup is that decades of planning depend on such fine margins. A country could plan meticulously and still be thwarted by an unlucky bounce of the ball or a bad decision by the referee. “If something goes wrong, everybody wants to rip up the book,” says Wilson. For spectators, however, this randomness offers a glimmer of hope.

Teams from Asia, Africa and North America remain the underdogs, but ought to have had more fairytale runs like South Korea’s in 2002. The 21st Club reckons there is a one in four chance a first-time champion will emerge this year. For one intoxicating month, fans around the world will forget the years of hurt and believe that their history books, like those in Montevideo’s museum, could be about to add a glorious new chapter.