The two faces of George Pell

The conservative cardinal has long been a divisive figure for Catholics.

Chrissie Foster won’t be in court when George Pell is sentenced on Wednesday. Foster could often be found sitting mid-courtroom after Pell was charged, her back straight, while barristers and witnesses fought over the detail of sex acts and intergenerational misery.

Instead of being there to watch the cardinal disappear, ghost-like, into the Victorian prison system, the relentless Foster will be in Canberra at a conference on the $4 billion national abuse redress scheme. “The sentence of Pell is the end of a process,’’ she tells The Weekend Australian. “That’s how I see it, whatever the sentence is. It’s like the job’s done.’’

Foster’s daughters Emma and Katie were in primary school when they were sexually abused by Melbourne priest Kevin O’Donnell between 1988 and 1993. Her children never fully recovered. Emma overdosed on medication and died in 2008, and Katie was hit by a car, suffering brain damage.

Foster and her husband Anthony, who died broken-hearted in 2017, sought help from Pell about the same time the cardinal, a jury has found, had sexually assaulted two choirboys in St Patrick’s Cathedral in Melbourne.

The Fosters found Pell to be dismissive and obstructionist.

Chrissie Foster says: “We have been the victim pool for the priesthood.’’

In many ways, Wednesday’s sentencing will be the beginning of the end of the legal debate about Pell. An appeal against the jury’s convictions is to be heard mid-year, two years after Sano taskforce detectives charged the 77-year-old cardinal with multiple offences.

Pell will receive a moderate to heavy sentence from County Court Chief Judge Peter Kidd.

Foster is one of thousands of people who have focused on Pell for decades, arguing he coldly obfuscated on sex abuse, protecting the church at every turn and implementing an inadequate redress scheme.

Now that Pell has been convicted of his own sex crimes, these voices have been supercharged, fuelling the national conversation about the cardinal and the church.

The smart among the survivor group, like Foster, know well that Pell’s ultimate future and legacy will not be decided in the swamp of social media or in the lounge rooms of the subjective moral majority.

It will be decided in the Court of Appeal, based on the evidence. As it stands, Pell is a convicted pedophile priest who has lost his Vatican job, his status, his reputation and his freedom.

Now it is a mad scramble by his legal team to cut his effective prison time to maybe a few months, which may become the most generous time frame possible for the cardinal, who has twin heart conditions.

The debate about the five guilty verdicts for assaulting the choirboys has been projected by some as being as black and white as Pell’s clerical clothes. The polarised arguments are about unambiguous guilt and unambiguous innocence. This is simplistic.

Those who have questioned the evidence on which Pell was convicted have foolishly and childishly been branded pedophile sympathisers. Somewhere in the middle is the absolute truth.

University of Melbourne law professor Jeremy Gans says there is a strong possibility Pell will win his appeal in June and be set free.

“Yes, I think there is a good chance that the court will decide that the jury ought to have had a doubt,’’ he tells The Weekend Australian.

Ever since Pell’s first court appearance in 2017, he has been shadowed by a group of deeply unhappy survivors, relatives and sympathisers, their numbers shifting according to the effectiveness of the suppression orders. Sometimes few in number, sometimes in their scores.

By the time of the sentencing submissions last week, scores of disgruntled people were in the main courtroom or the spillover room, watching as the judge grumpily pulled Pell’s silk Robert Richter into line.

The Pell critics don’t come from one parish; they come from all over Australia: the sex abuse crisis followed the cardinal almost from the moment he landed back in rural Victoria in 1972 in the Murray River town of Swan Hill.

Nor do these people tell the same story; such has been Pell’s influence and status in the church that he has been blamed for many, many things.

Pell was convicted on charges relating to his time in Melbourne but his downfall began in Ballarat, a diocese that spreads across western Victoria and was polluted by thousands of cases of Catholic abuse across many decades.

One of the abusers, Gerald Francis Ridsdale, offended against hundreds. For reasons that are partly Pell’s fault, the Pell name was forever polluted by his association with Ridsdale. The survivors, their families and their friends, never forgave him.

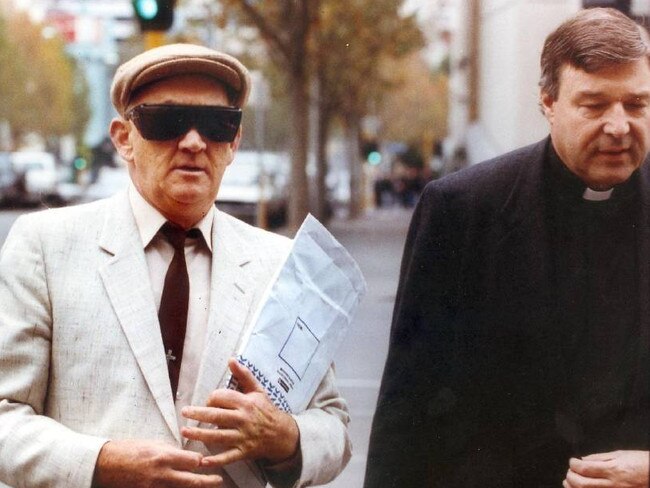

Pell foolishly attended court in support of the disgraced priest in 1993, when Ridsdale was emerging as probably Australia’s most prolific Catholic abuser.

Pell told the sex abuse royal commission: “I now realise that was a mistake. I walked with him following the Christian conviction that it’s an appropriate activity to be kind to prisoners … the separation of the sheep from the goats is their acts of kindness we do to people, including those who are prisoners and those who are at the bottom of the pile like Ridsdale.’’

From the moment Pell walked into that court with Ridsdale, he was a marked man, the enmity spreading like a cancer into Melbourne, then Sydney, then Rome.

No one who was connected with Ridsdale would forget.

Indeed, in the committal hearing it was suggested Pell’s association with Ridsdale was the trigger for the so-called Operation Tethering police investigation into Pell in September 2015.

There was no formal complaint against Pell but one investigator, senior constable David Rae, told the court two of Ridsdale’s victims had mentioned Pell.

One had reported being with Ridsdale and being introduced to Pell at St Patrick’s Cathedral in Ballarat. The court heard Ridsdale’s other victim had alleged Pell walked by while Ridsdale sexually assaulted her.

Pell’s silk, Robert Richter: “In relation to Pell, that was nonsense, I suggest.’’

Rae: “I suggest otherwise.’’

An internal police document from 2015, headed “Inappropriate behaviour”, mentioned Pell’s cohabitation with Ridsdale at Ballarat East in the 1970s, and his apparent close relationship with Ridsdale. Pell and Ridsdale shared accommodation at St Alipius in Ballarat, a school where four Christian Brothers would molest their way through the school.

There is no evidence that Pell had knowledge of or was involved in that offending, but in Ballarat he is reviled by many for what they believe is guilt by association.

The victims understandably view dimly Pell’s role as a priestly consulter in helping shift Ridsdale from the parish of Mortlake in 1982 to another job, after the church discovered Ridsdale had been abusing again.

Pell denied knowing why Ridsdale was shifted at the behest of the then bishop of Ballarat, Ronald Mulkearns, a big-drinking churchman who is now dead.

The precursor to the sex abuse royal commission was a Victorian parliamentary inquiry into non-government institutional abuse, which gave birth to the Sano police taskforce.

The Weekend Australian understands there were no concrete complaints to the committee about alleged Pell abuse.

However, committee members did discuss a previous church-instigated inquiry led by retired judge Alec Southwell, which was set up at the turn of the century to investigate claims that Pell had offended against a boy in Victoria many years earlier.

Southwell investigated a claim by a middle-aged man that he had been abused by Pell at a seaside camp in 1961 when Pell was a young seminarian and the accuser was 12. Pell allegedly groped the child’s genitals. Southwell, in what was a diplomatic ruling, found in favour of neither Pell nor the alleged victim. He did not substantiate the complaint.

“I am grateful to God that this ordeal is over and that the inquiry has exonerated me of all allegations,” Pell said in 2002. But the complainant’s lawyer, Melbourne-based Peter Ward, also alleged vindication.

“We’re delighted with the hearing. The commissioner accepted that essentially we were honest in our account of the molestation. Our honesty has been accepted,” he said.

Then there is the broader question of Pell’s at times clumsy, dismissive rhetoric, best evidenced by his comment to the royal commission on what he knew and when about Ridsdale.

“I don’t know whether it was common knowledge or not. It’s a sad story but it wasn’t of much interest to me,” Pell told the commission. Asked to expand on why he would be uninterested, he said: “The suffering, of course, was real and I very much regret that, but I had no reason to turn my mind to the extent of the evil that Ridsdale had perpetrated.’’

His hardline rhetoric is legendary. At a 2002 World Youth Day event in Canada, Pell made global headlines by saying “abortion is a worse moral scandal than priests sexually abusing young people”, since abortion was “always a destruction of human life”.

It’s fair to say the Left loathes Pell. Many on the Right, however, revere him.

Those who know him well, like prominent Catholic educator Stephen Elder, sense Pell is the victim of a witch-hunt that began with Operation Tethering.

Elder, an adjunct professor at the Australian Catholic University, has known and trusted Pell for decades. “Be afraid; be very afraid. This should be the takeaway lesson from the flawed criminal prosecution of Cardinal Pell,’’ Elder tells The Weekend Australian.

“Pell was convicted of decades-old criminal offences on the sole word of a single accuser who never appeared in open court before the jury. Instead, the crown was allowed to build its case around videotaped testimony recorded during a previous prosecution that ended in a mistrial.

“Nor is any credible forensic evidence presented to support these allegations of criminal wrongdoing alleged to have been committed way back in 1996. And the only other potential first-hand witness, a second alleged victim, died years ago after telling his mother he had never been victimised.

“Pell has long been a polarising figure in the Catholic Church, beloved by some for his unapologetic conservatism while detested by others for precisely the same reason. But the civil liberties issues at stake in the Pell prosecution far transcend the Cardinal’s personal popularity — or lack thereof.

“Regardless of your subjective feelings about Pell the man, the perversions of judicial due process blighting this criminal case should scare the hell out of everyone.’’

The Weekend Australian has established that the chief witness in the prosecution case was deemed by key people familiar with the case to be both believable and compelling in his own way.

But this doesn’t strip away from the argument that there a series of questions remain about whether the jury got it right.

This is not to support a convicted sex offender as Pell is until June at least. But it is to adhere to the lofty ideal that people shouldn’t be jailed for crimes they may not, on the basis of the evidence, have committed.

The key questions around the prosecution are well outlined by Elder but also include whether the jury took sufficient notice of what the defence said was the implausibility of the crimes.

How, principally, could Pell have committed these crimes within the walls of the cathedral after a solemn mass, over five to six minutes, while the door to the normally busy priests’ sacristy was open and it was normal practice for the then archbishop to be with someone.

Anything is possible, but is it probable?

It takes a lot to silence Jeff Kennett. The former Victorian premier doesn’t want to talk about the Pell matter to The Weekend Australian but it is on the record that he hauled the then archbishop of Melbourne into his office in 1996 and ordered him to clean up the church’s act.

Soon afterwards, Pell introduced the Melbourne Response compensation scheme.

Kennett did, however, support John Howard and Tony Abbott in their right to back Pell after the verdict was made public, adding that he has his doubts about the outcome.

“I know it is easy to be critical and I accept the legal system as it is,’’ Kennett told Seven’s Sunrise program.

“I can’t reconcile what has been decided with the person I knew, but there again, I didn’t hear the evidence, and I accept the decision. But please don’t undermine any individual for simply exercising his or her right based on their knowledge of any other individual.’’

It pains Pell’s critics that he has so many high-profile supporters. He also has many behind the scenes who swear by his generosity, intellect and humanity.

Which makes an already ambiguous story even more bewildering. What we so often saw of the public Pell was not what was going on in private.

This is the great contradiction that has dogged his career. George Pell. Friend or foe?