The slaughter of Skabrnja’s innocents

Secret files blame a Sydney man for one of Serbia’s worst war crimes.

Boro Pekmezovic and Srboljub Djokic are proud former infantrymen from the Loznica brigade, a force of about 7000 that protected and expanded Serbian interests in the breakup of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s.

“Serbs don’t run away,’’ says Djokic, president of the War Veterans Assembly in Loznica, a sleepy semi-rural Serbian town close to the Bosnian border.

In a smoke-filled coffee shop on the canal that sweeps through Loznica, he says he and his fellow war veterans would do the same again, even as they fight for pension recognition for their years in service.

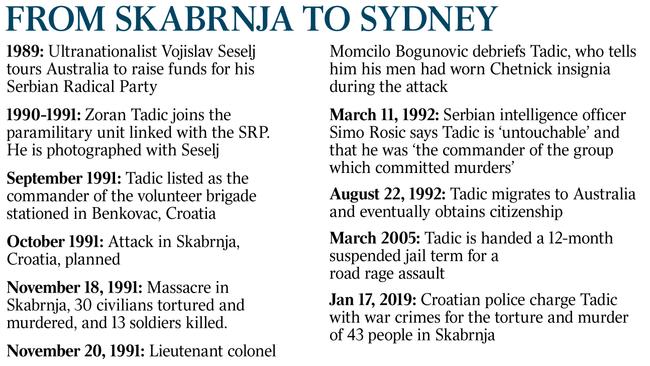

Yet there is a sharp intake of breath and a distinct pause when it comes to the question of paramilitaries among the townsfolk — such as the now Australian citizen Zoran Tadic, who joined the political rallies of Serbian Radical Party leader Vojislsav Seselj in late 1990 and early 1991.

The Australian has today revealed how Serbians living in Australia raised money for Seselj to found his ultra-nationalist party, which recruited and promoted the paramilitaries.

In Loznica, where Seselj urged disaffected men to join his cause nearly three decades ago, there is a sip of coffee, another drag on the cigarettes and ultimately a shrug.

“It’s political,’’ they say.

For many Serbs, patriotism and a fierce defence of the homeland is paramount, yet there is a closing of the conversation. For even now, a quarter of a century on, the Chetnik paramilitaries are a potent force.

The Zoran Tadic living in Heckenberg, western Sydney, is an overweight, angry father of three. We know this because 13 years ago he was convicted to a suspended one-year jail term for a road rage assault.

He threw a middle aged stranger on the road in front of oncoming traffic because her friend had been too slow to take off when the traffic lights changed.

Croatian police allege Tadic was a feared paramilitary leader. He allegedly commanded and actively took part in one of the country’s worst war crimes, the torture and slaughter of 30 mainly elderly villagers and 13 soldiers in Skabrnja in 1991.

For more than 26 years Tadic has evaded scrutiny, even though his name has been mentioned throughout some of the biggest war trials in The Hague, including those of former Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic and Milan Martic, former president of the Krajina region.

The Australian has uncovered evidence from these trials which shows Tadic was a Loznica paramilitary.

He was believed to be at the Loznica central park, Vuk Karazdic, during the fiery rallies of Seselj on the Serbia-Bosnia border region from early 1990 and he joined the special forces paramilitary group, which worked in conjunction with official army operations, conducting black operations.

Tadic was well connected, and possibly already a member of the State Security Service before he joined the paramilitaries, reports suggest.

In the Skabrnja attack on November 18, 1991, Tadic’s men, commonly referred to as the Chetniks, blackened their faces with boot polish and wore camouflage clothing with small insignia differences to the regular JNA army.

Immediately after the atrocity, Tadic was promoted to be the special security officer for the Benkovac Territorial Army. A photograph from the time shows a confident Tadic wearing his camouflage gear walking next to Seselj.

Documents uncovered after Croatia liberated Benkovac indicate Tadic wasn’t well liked by some jealous colleagues, especially as he used his connections’ to insist on being given a confiscated Croatian house. He was suspected of concentrating on his personal business, presumably at the expense of his intelligence work.

Yet that privileged role wasn’t to last. About nine months after Skabrnja, Tadic migrated to Sydney.

Paramilitary men allege Tadic fled “as far away as he could in a vast country’’ to distance himself from superiors who were facing difficult questions about the scale of the massacre.

Whether he was assisted by those top men to obtain Australian residency, and then citizenship, is unknown, although Croatian police believe he had some form of assistance from the Serbian government to obtain the required paperwork for migration.

Pekmezovic says that during the country’s sanctions between 1991 and 1999 it was very difficult to go to Australia.

“You had to have contacts,’’ he says.

But almost as soon as the paramilitaries had returned to base after the massacre, there was concern among Serbian military officers that the paramilitary actions in Skabrnja and other Croatian majority towns was being confused with the regular military campaigns.

Army officers castigated Tadic’s paramilitaries as alcoholics and psychopaths.

The chief of the 180th motorised brigade, lieutenant colonel Momcilo Bogunovic, was told that the actions of the paramilitaries immersing themselves in the territorial army and the regular army (JNA) “only embarrassed the JNA by committing crimes while under the protection of JNA tanks”.

The Australian can reveal that this concern and subsequent internal Serbian investigation has provided contemporaneous evidence linking Tadic and the men he commanded to the massacre. One of the documents, a secret military report compiled by a Serbian intelligence officer, lieutenant Simo Rosic, and dated March 11, 1992 — three months after the massacre — says Tadic “was in a sense untouchable’’.

A certified translation of Rosic’s reports labelled “Military Secret, Strictly Confidential’’ shows he initially believed Tadic may not have been directly involved, but that Tadic would know who was. However, within days Rosic had obtained further information and submitted a revised report which is damning of Tadic.

He alleges in that March 11, 1992, report: “Zoran Tadic was the commander of the group which committed murders and apart from him, Serbian volunteers Kizo, Pajser and Zoran Dondor were also committing murders.’’

Another of the Serbian paramilitaries from Loznica, Ljubisa Vucicevic, was shooting indiscriminately and lobbed an activated bomb into one basement where people were sheltering.

The plan to terminate the local Croatian population from their homes in Skabrnja had been formulated by October 1991 and a month later, on November 17, Ratko Mladic, the head of the JNA army 9th brigade, wrote in his diary about the need to complete the campaign in combat by mopping up the sector properly. He suggested that a two-day attack may be necessary in Skabrnja.

He then added ominously: “Wipe it out.”

In early on November 18, Mladic’s men, with scores of tanks and aerial support, attacked Skabrnja in a pincer movement.

Croatian policeman Marko Miljanic, who lost his brother, father and other relatives in the slaughter, told The Australian the Serbian tactics were to wipe out the population and send a terrifying message to other people in Croatian majority towns to flee or perish.

In late 2017, the Humanitarian Law Centre in Belgrade demanded a local Serbian prosecution file be opened on Skabrnja and the Serbian leaders of the attack because it was “so massive’’.

Legal program director Ivana Zanic tells The Australian: “This was a huge massacre and a lot of people were killed there.”

“We wanted the Serbian prosecutors to look at indictments and not just for crimes committed by Croatians.

“We believed some of the accused perpetrators of Skabrnja were still in Serbia. It was a shock to discover one of the accused was in Australia.”

Yet 27 years ago the scale of the torture and slaughter was well documented.

Bogunovic conducted debriefings within days and interviewed Tadic about what happened.

Under the heading “Lieutenant Tadic’’, Bogunovic lists several points. Tadic had raised with him some concerns that his men had worn Chetnick insignia during the attack and so they couldn’t be used for further operations.

Tadic told him that “KV’’ tried to stop the killing but they then wanted to kill him. Another point says: “He kills a man as soon as he sees him. He kills dogs”. Tadic also informed him that soldiers in the company began to loot the town.

Bogunovic brought in Major Branislav Ristic of Serbian intelligence to conduct a review. Within two weeks, Ristic knew some of the most gruesome details, which ended up being tendered in Milosevic’s war crimes trial.

Another Military Secret document, dated the end of September 1991, was also submitted in the Milosevic war trial and describes how Tadic was the commander of the volunteer brigades at the time.

During his investigation, Ristic blamed the Skabrnja atrocity on an “internal enemy’’ and much of his information came from a secret agent, codenamed Beograd-1.

Beograd-1 told him territorial army commander Goran Opacic informed a meeting that mainly women and elderly people were killed in Skabrnja.

A volunteer Chetnik named as Jaro-Jere had stood out in the killings along with his friend Ljbusia.

An active soldier moved among them with a rocket-propelled grenade before he shot an old man.

Opacic said the man exploded so forcefully that only his leg stayed close by.

He also detailed how “Zoric’’ was walking around with a bag of human ears.

Following Skabrnja there were other atrocities at Nadin, Saborsko, and then Vukovar and Bruska.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia has convicted political leaders Milan Martic (35 years) and Milan Babic (13 years) for war crimes, including those committed at Skabrnja.

A case against State Security Service leaders Jovica Stanisic and Franko Simatovic is ongoing. In the Zadar County Court back in 1994, 17 people were convicted in absentia of war crimes for the killings in Skabrnja. Another two, Jovan Badzoka, served 10 years in prison and Zorana Banic served six.

The County Court in Split, Croatia, is preparing an extradition warrant for the arrest of Zoran Tadic.