The long, non-stop leap to London

A Qantas flight tomorrow will leave Perth for London, nonstop, showing how far the aviation industry has come in 75 years.

At four o’clock in the pre-dawn darkness of Perth on June 29, 1943, residents were woken by the deep-throated rumble of aircraft engines roaring down the Swan River from Nedlands.

Those who rose to see what was causing the disturbance could discern nothing. That was the plan, for this flight was a top-secret, mission impossible project that created aviation history.

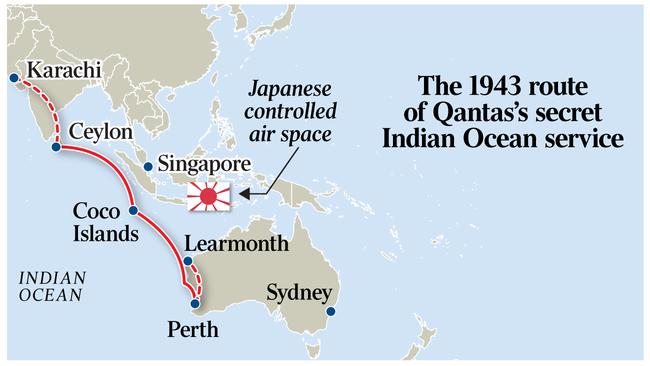

The roaring engines belonged to a black-painted Catalina flying boat, taking off without lights on a moonless night — the first flight of the little-known Double Sunrise service pioneered by Qantas to restore the air link between Australia and Britain, broken the previous year when Japan took control of airspace to our north.

The Double Sunrise Catalinas set new records for the world’s longest nonstop commercial aviation flight — 5630km from Perth to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), which took more than 27 hours.

Tomorrow, a new Qantas Boeing 787 Dreamliner named Great Southern Land will lift off from Perth airport and set course for London, nonstop. This will be another record-breaking flight by Qantas — nearly 15,000km, taking 17 hours and 20 minutes.

It’s a remarkable demonstration of how the aviation industry has progressed in the past 75 years. Tomorrow’s flight will be three times longer than the pioneering Perth-Ceylon Catalina flight, flown 4½ times faster in two-thirds of the time it initially took.

The Qantas Dreamliner will carry more than 250 passengers. The Catalinas had capacity for just five because most of the internal space in the aircraft was taken up with fuel tanks.

The 17-hour inaugural flight also offers a contrast with the 1947 Super Constellation Sydney-London service that took 55 hours flying time across four days and involved seven refuelling stops.

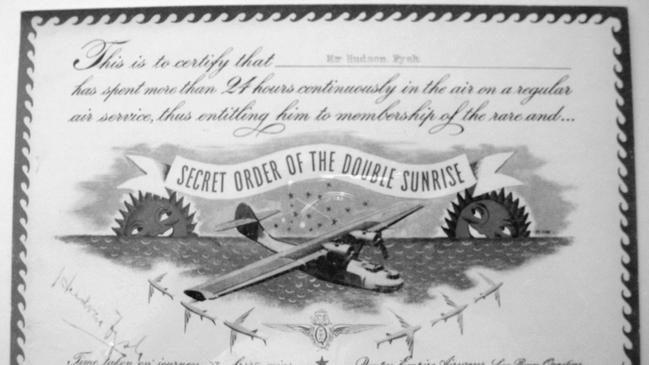

The Double Sunrise service took its name from the fact that passengers and crew would see two sunrises during the flight; one an hour or so out of Perth and the other two to three hours before landing at Lake Koggala on the southern tip of Sri Lanka.

Passengers on the nonstop Dreamliner to London may see none in the northern winter. In the southern summer, it will still be light when the flight leaves Perth at 7pm local time. It lands at Heathrow shortly after 5am London time the following day. Return flights leaving London at 1pm local time and arriving in Perth at 1pm local time the next day will involve a single sunrise.

The story of the Double Sunrise service is told by former Qantas publicity chief Jim Eames in his recently published book Courage in the Skies, which highlights the largely unsung efforts of Qantas pilots during World War II.

Despite aircraft shortages, loss of vital planes and equipment, bureaucratic stonewalling and countless bombing raids by the Japanese, Qantas personnel were involved in some truly heroic deeds during Australia’s darkest hours in 1942 and 1943.

They were the last flight out of Singapore before it fell to the Japanese. They survived bombs at Kupang in west Timor and they snatched diplomats and military officers from under the noses of the Japanese in Java.

They flew through appalling weather and dangerous skies among the mountain peaks of Papua New Guinea on “bully beef runs” to keep Australian soldiers supplied with food and arms at Gona and Buna at the northern end of the Kokoda Track.

They were shot at and shot down. They lost eight aircraft and 72 lives. Yet the Qantas crews were never recognised. Unarmed, they faced the same dangers as enlisted men and women piloting their flying boats and cargo planes into enemy airspace, but successive governments have ignored calls for them to be given formal recognition for their bravery and service, because they were civilians.

One Double Sunrise flyer, pilot and navigator Rex Senior, in his final interview before he died aged 95 in 2015, said: “We were aware we were doing something never done before. It was very exciting, and when we reached our destination, we realised we had managed to do what aviation authorities believed was impossible.”

In a final interview he said: “We were aware we were doing something never done before. It was very exciting, and when we reached our destination, we realised we had managed to do what aviation authorities believed was impossible.”

When Qantas launched its audacious plan to restore the vital Australia-Britain wartime link, the longest commercial route using Catalinas was between Hawaii and the US west coast, a distance of 4000km.

The Qantas pilots and engineers knew they could do better than that because they had undertaken delivery flights of 19 Catalinas from California to Australia in 1941. The first delivery flight was the third transpacific flight made.

The standard route took them via refuelling stops at Pearl Harbor, Canton Island and Noumea, but as the pilots learned how to finetune their engines, reduce fuel use and exploit tail winds, they became attracted to the idea of possibly skipping Noumea.

In October 1941 three Catalinas left Canton Island en route to Sydney. As they approached Noumea, pilot Russell Tapp and his navigator calculated that in fine conditions they could reach Sydney, but if the weather deteriorated they could make a safe landing in Brisbane. They decided to fly on and arrived in Sydney after covering nearly 5000km in 26 hours. They had two hours of fuel left.

This achievement planted the seed for the possibility of re-establishing the fractured Australia-Britain link.

At first, civil aviation authorities rejected a proposal put by Qantas chief Hudson Fysh. Director general of civil aviation Arthur Corbett was adamant: “Such a proposal would be little short of murder and I would strongly oppose risking crews’ lives,” he wrote.

He had a point: the plan would involve unprecedented distances for unarmed aircraft carrying high-ranking military men, diplomats, mail and top-secret cabinet communications, flying in daylight through Japanese controlled skies, within range of Japan’s land-based fighters. Not even the Australian territory of Cocos Islands could be used for refuelling because it was subject to frequent Japanese reconnaissance flights.

But Fysh continued to lobby and set up his Long Range Operations Division under pilot Lester Brain. The division consisted of 10 captains, six first officers, eight radio officers and 13 engineers, headquartered on the banks of the Swan River at Nedlands.

By 1943, wartime necessity overcame bureaucratic barriers and the Cats were readied. They were painted black and extra fuel tanks were added. One of the remarkable things about the Cat was its ability to carry almost its own weight in fuel; they were designed with an all-up weight of 12 tonnes, but the Qantas team developed techniques to allow the aircraft to take off with seven tonnes of fuel on board, four tonnes overweight.

This meant an exceedingly long take-off. Senior recalled how the pilots put on full power at Nedlands to achieve lift-off from the Swan River almost 12km later. “We often cleared the bridge at Fremantle by just 100 feet,” he said. “I don’t know what the local residents thought.”

On return flights the take-off was equally difficult. The grossly overweight aircraft had to taxi into the inlet of a creek feeding Lake Koggala to achieve enough distance for a safe lift-off.

The first flight to Ceylon, under the command of Tapp with Senior as first officer, arrived on July 1, 1943. The return was set for July 7, but three hours out of Lake Koggala it was discovered the sextant, a vital instrument for star-shot navigation, had been left behind. The crew had no choice but to return and try again on July 10.

Eames reports: “Once again, gremlins struck, this time in the form of food poisoning. Again under the command of Russell Tapp with Bill Crowther as navigator and carrying 24kg of diplomatic and military mail, they were several hours out of Koggala when three crew became violently ill and had to take to the bunks.

“A quick decision had to be made whether to return once more, but with Crowther available to sit in at the controls it was decided to continue. Such circumstances aboard a cramped Catalina and with one tiny toilet … at the back of the plane hardly bore thinking about. Rex Senior would later describe heading for the toilet to find another sufferer there and demanding: ‘Get off that thing fast or I’ll sit on your lap!’ ”

At times, crews had to search for favourable winds. A navigation fix revealed the first return flight’s ground speed was a disastrous 120km/h, which meant there would not be enough fuel to reach Perth. “They gingerly coaxed the Catalina several thousand feet higher until it found the wind stream and were relieved to see their ground speed increase to about 220km/h, eventually arriving at Nedlands after 27 hours and 40 minutes in the air.”

This gave the Cat an average speed of about 200km/h.

Tomorrow’s Dreamliner flight will have a take-off weight of about 250 tonnes, half of that being fuel. It will cruise between 35,000 and 40,000 feet at a speed of 900km/h.

The Catalina Double Sunrise service made 271 flights without loss of life or aircraft. The Cats also took on the next leg, 1400km to Karachi (now in Pakistan), linking up with BOAC flights through the Middle East to London. They linked London, British forces in India and Burma, and Australia.

In secret, the Qantas Catalinas carried 858 passengers and 100 tonnes of mail and flew more than two million kilometres to break the Japanese blockade of our north. Passengers were given a certificate confirming their membership of the Secret Order of the Double Sunrise. It was, as Eames says, “a most fascinating and romantic undertaking’’.

Courage in the Skies by Jim Eames is published by Allen & Unwin ($29.99).