Steel magnate Gupta’s iron will

Beyond Whyalla, Sanjeev Gupta is building a global empire by buying struggling or closed plants.

Early last year, Sanjeev Gupta was an unknown interloper in the race to buy the assets of the collapsed steelmaker Arrium.

Doing the rounds to introduce himself and make his case, Gupta complained that he couldn’t even get a response from the receivers KordaMentha, despite having what he claimed was a superior bid for the Whyalla steelworks.

He persisted, badgering creditors and eventually forcing KordaMentha to overturn the favoured-bidder status of a consortium led by Korean giant POSCO.

Fast forward to this week and Gupta is being hailed by Scott Morrison as a saviour who will make Whyalla “the comeback city” in the “turnaround state” of South Australia.

The catalyst was the announcement of a major expansion plan for the Whyalla blast furnace to realise the long-held dream of value adding to our abundant coal and iron ore products rather than shipping them off as unprocessed bulk commodities.

“If you know the man it is not that dramatic,” says Ray Horsburgh, the Smorgon Steel veteran who joined Gupta’s GFG Alliance bid for Whyalla and now sits on the board.

“He is one of the most forward-thinking people you could meet.”

The Arrium play has already paid dividends. Gupta announced last month that the business, which includes the Smorgon electric arc furnaces on the east coast, would make about $700 million this year — more than Gupta paid for it in June last year.

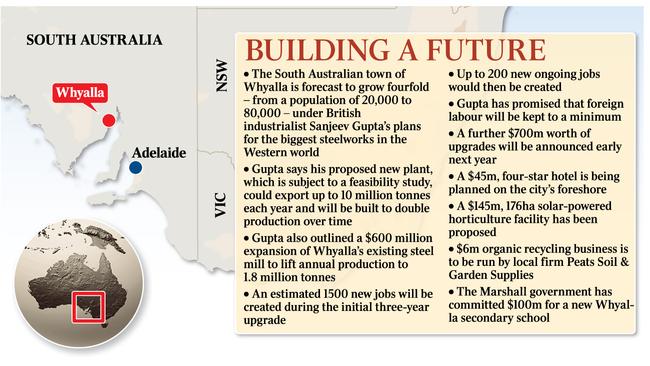

Now the Indian-born, English-educated founder of Liberty House is doubling down, announcing a $600m plan to expand production at the existing plant from 1.1 million tonnes a year to 1.8 million tonnes.

That would be the first stage of a plan to build a “next-gen” steel plant capable of producing 10 million tonnes a year, making it the biggest in the world.

In typically grandiose fashion, Gupta says the “cutting-edge transformation plans” for which he has signed contracts worth $600m are just the beginning of what he wants to do in the region.

“Utilising almost perfect local conditions — our own infrastructure including a deep-sea port; rich local resources; and unrivalled community passion — we now plan to build a new steel plant, one of the world’s largest, right here in Whyalla.”

It’s an incredible — not to say implausible — plan to some. But it would not be the first time for Whyalla or for South Australia.

The last time it happened was when Whyalla was a BHP town. As Horsburgh points out, it was founded in 1901 as a BHP outpost. Hummock Hill was the end of a tramline bringing ore from Iron Knob in the Middleback Range. The ore was used at Port Pirie and also shipped to BHP steelworks at Port Kembla before BHP built the Whyalla steelworks in 1965.

Gupta has his doubters, with British newspapers including The Times and The Financial Times raising questions about the sources of his finance for his global acquisition spree, and a tally of investment plans that now tops $US14 billion ($19.4bn).

But the Arrium deal follows a well-worn pattern. In just three years Gupta has emerged from a wealthy Indian commodity-trading family to hoover up a string of struggling or closed plants stretching from Wales to Romania to India and the US, fashioning them into a $US15bn empire.

He shelled out $US320m last week to buy Texas-based metal producer Keystone, doubling down on a commitment to the US after acquiring the mothballed Georgetown steel plant in the US last year.

GFG also scooped up Europe’s biggest aluminium smelter, Dunkerque, from Rio Tinto for $US500m in January, adding to other deals on the continent, including steel mills owned by Indian rival Tata Steel.

In February the Prince of Wales pushed the button on a restart of the Rotherham steelworks in South Yorkshire that had been closed by Tata Steel in 2015.

In Australia, Gupta shot to prominence after rescuing Whyalla along with the purchase of a NSW coking coalmine from Glencore and the promise of $1bn of investments in solar, wind, battery and pumped-hydro generation to support the now profitable steel business formerly owned by Arrium.

Just how he has done it may become a little clearer next year. The industrialist plans separate sharemarket listings in Australia and the US next year to house his “greensteel” assets — scrap recycling plants largely powered by renewable energy.

That would provide greater transparency as underwriters seek an explanation about the structure of his sprawling businesses, including a string of investments in Australia.

In large part the former commodity trader has ridden the cycle, snapping up assets at beaten down prices.

Since bottoming out in June 2016 — when Arrium was caught in the middle of a debt-funded expansion and went broke — the price of steel has more than doubled, minting Gupta a fortune.

Horsburgh, who spent 15 years running a business that converted around two million tonnes a year of scrap metal into products like steel bars and billets that competed with Arrium, says market conditions have also moved in favour of local value adding.

Local labour costs made it more economic to ship bulk iron ore and coal for conversion into steel to developing nations where growth rates were higher and wages lower. But wages are rising in markets around the region and new steelmaking technology requires less labour, reducing the differential.

“He just thinks that with Australia having all of these natural resources we should be doing the value adding before we export it,” Horsburgh says.

“The carmaking, construction, whitegoods booms are all happening there, so why aren’t we doing the value adding here before we ship it?”

Critics also point out that the smiling and relentlessly optimistic Gupta has been adept at securing government support for his plans around the world.

Always keen for growth and rejuvenation, they have been willing to offer grants and concessions that help improve the viability of a given plan and secure jobs for the region.

The Whyalla rescue came with a $50m package from the then Labor state government. And in announcing the expansion plans this week, Gupta said the investments to make it happen will be financed through GFG’s own resources as well as those of suppliers “and will likely require support from the South Australian and federal governments”.

Those same governments, not to mention Whyalla Mayor Clare McLaughlin — who is basking in predictions of the city’s population booming from 20,000 to 80,000 — are hoping he can pull it off and say they are willing to offer support.

Industry players have given their cautious backing to Gupta’s ambitious mega steel plant. Australian Steel Institute chief executive Tony Dixon says it’s important for the country to have a long-term steel industry.

“I hope he can provide the pathway forward,” Dixon said.

The cycle remains in his favour, with infrastructure spending on giant projects such as the inland rail line, Sydney’s WestConnex toll road network, Brisbane’s Cross River Rail and a potential Melbourne airport train line not expected to peak for years.

However, others warned any cyclical downturn could render an expansion uneconomic.

“If we see a big swing in the dollar, a project like this would really struggle to compete,” Fat Prophets resources analyst David Lennox says.

Sydney-based steel trader Sanwa says it is watching the project with interest.

“The Australian market at the moment is short of structural steel,” Sanwa chief executive David Roberts says. “Whether it’s short enough to justify an extra 50 per cent capacity out of Whyalla, I don’t know.”

Like any expansion or new project, its success will partly hinge on the prevailing market conditions when it comes online.

“It depends on how the market is at the time it comes online,” Roberts says.

“These steel mills work to cycles and if you get it wrong, by the time you put in the capital infrastructure and you start producing, the cycle might have moved on.”

Still, Gupta shows little sign of slowing down on his global expansion plans.